The appellation, “Río de Las Animas”—the River of Souls—was written in the journal of Spanish colonizer, Juan Maria Antonio Rivera while crossing the Animas River on horseback in 1765 (Durango Herald). One can only imagine what sights lended to this name.

Perhaps Rivera sensed the looming possibility of souls swimming in the water? Or, did he think the cottonwood branches poking through the currents resembled bleached bones? Maybe the sandbars and deep waters whispered like voices.

Much like its name, the resilience of the Animas River against environmental catastrophe is an enigma. Emerging from glacial origins and surviving pollution from mining and fire, the river endures as one of Colorado’s most unique waterways. It serves as a vital source for the communities it hydrates, as well as the fish and river runners who ride its untamed current.

Glacial Origin

The Animas River Canyon’s story begins a long time ago…

It begins in the Pleistocene, a.k.a. the last epoch of the Ice Age.

In an act resembling nature’s masterpiece, this expansive valley—stretching a whopping 50 miles—was sculpted by a crystalline glacier’s remarkable force (UNM, 28).

The glacier reached ten miles northeast from present-day Silverton and extended to Durango. It drew its power from over 75 freezing drainage basins, with ice thickness reaching a staggering 2,000 feet (UNM, 29).

Today, the glacier melt is evidenced by the erosion seen in Animas Valley. Ancient imprints manifest as moraines: unconsolidated rock debris scattered across the landscape by the moving glacier. Former stream channels, now dry and adorned with riverside vegetation, serve as a living testament to the glacial origins that have intricately shaped the canyon’s current appearance (UNM, 29).

The cotton candy-blue glacier is now relegated to the realms of our imaginations. The Animas River Canyon, however, still bears the indelible marks of the past.

Resilience Embedded in History

Water is our life…It’s who we are. We don’t know what will happen…The water is being shut off. We are confused…Anger starting to boil. Our elders have sad misty eyes…This is so surreal. Government sez farmers will get compensated…Payday time. Lawyers licking their chops…Water tests ok. Rez Prez sez turn on water…EPA steps out. Water must be ok…Bye, bye.

– A poem recited, beat-style, by Duane “Chili” Yazzie, Diné Farmer in 2015 (HCN)

Tragically, the pure, glacial origin of the Animas River was tainted by mining pollution beginning in the 1860s. Prospectors, having drained California of its gold, decided their next rush would be to Colorado’s peaks. Undeniably crazed, they installed factories known as smelters throughout the San Juan Mountains to convert ore into metal.

The effects of mining did not fade away like the generation who innovated it. In 1942, the federal government purchased and repurposed an old smelter in Durango for uranium milling. Eventually, the private company, Vanadium took over, and water quality took a sharp nosedive. At its worst, the mill processed 500 tons of ore daily, yielding a mere 6 pounds of uranium per ton while generating a substantial 997,000 pounds of tailings, laden with toxic chemicals they dumped right into the river (HCN).

In the aftermath, the toxic brew in the Animas River revealed alarming levels of radium. Water, mud, and algae samples collected two miles below the mill exhibited radioactivity 100 to 500 times higher than control samples taken above the mill. The severity extended beyond the river, affecting communities like Farmington, where tap water consumed by residents carried radioactivity levels ten times that of Durango’s tap water (HCN).

The Gold King Mine Spill

As recently as 2015, the Animas River confronted more haunting repercussions of mining during an unintended release, deemed the Gold King Mine blowout. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) inadvertently let loose more than 3 million gallons of water from an abandoned mine, carrying a toxic payload of heavy metals like iron, arsenic, and lead. This release unfolded as workers breached materials, unknowingly unleashing the contaminated, mustard-colored water into the river (CO Encyclopedia).

The river, already burdened with the toxic metals from upstream mining and the uranium mill, was left virtually devoid of bottom fauna due to the new assault, accentuating the ecological toll of mining (HCN).

Steps Taken Towards Restoration

For many years, federal intervention proved inadequate in restoring and regulating activities aimed at conserving the Animas River. Faced with a drop in uranium prices and anticipating public outcry, the Vanadium Corporation closed the Durango mill in 1963, relocating operations to Shiprock, New Mexico (HCN).

The scene shifted dramatically in 1986 when the Department of Energy stepped in with a $500 million cleanup effort, utilizing taxpayer dollars to rectify a mess it had initially funded. This monumental undertaking included the demolition of the original smelter, a moment etched in memory as its tall brick chimney crumbled into a cloud of dust, symbolizing a commitment to environmental recovery (HCN).

Fast forward to 2015, after the EPA’s accidental release. Water sampling efforts were deployed to protect the drinking-water supplies of communities along the Animas River.

Additionally, aquatic wildlife underwent ongoing testing to assess the safety of consuming fish from the river’s contaminated reaches.

While the plume passed and the water returned to its regular silty state, the EPA, alongside state and county health departments, reassured communities along the Animas and San Juan rivers that all was back to normal (HCN).

Yet, the river has scars. Aquatic wildlife has been and will continue to be tested. There are patches of riverbed that may never flourish like before. In the short term, water sampling has protected the drinking-water supplies of communities along the Animas River (HCN). Unfortunately, the long run for others suffering from the trauma of disease, death, and loss can never be sampled away.

Battling the Flames – The 416 Fire

On June 1, 2018, Columbine District Forest Rangers received their 416th incident call. A fire, influenced by drought and an exceptionally low snowpack, had broken out in the San Juan National Forest (Storymaps).

Flames ravaged approximately 54,000 acres, predominantly in the Hermosa Creek watershed. This area, historically recognized as one of the Animas River’s purest tributaries, bore the brunt of the wildfire’s impact (Durango Herald).

As the monsoons arrived in mid-July, the aftermath of the fire manifested in large amounts of debris flowing into Hermosa Creek and the Animas River. The resulting mudslides and debris flows not only inflicted property damage but also led to catastrophic fish mortality (Storymaps). Investigations revealed just 28 pounds of trout per acre, a 64% decrease from the Animas River’s historical average of 78 pounds per acre (Durango Herald).

The subsequent winter, a heightened and sustained runoff during the spring and summer alleviated the blow. This played a pivotal role in purifying the river bottom—an indispensable habitat for a myriad of fish and insects (Durango Herald).

The Case for Freedom

The Animas River survived pollution. It flows freely without dams, all the way from Animas Forks (elevation: 11,120 feet) to before its confluence with the San Juan River in New Mexico. It is nothing if not a unique and untamed river. Surprisingly, it’s not yet granted protection from new dams, but rather a nominee under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (Fort Lewis College).

Advocates champion its cause, highlighting its biodiversity, from rainbow and brown trout to the inconspicuous mottled sculpin, a bottom-feeder that thrives only in clean, cobble-bedded mountain streams (CO Encyclopedia). Despite the legal hurdles that even a formidable river must navigate, the Animas River’s biodiversity and unrestrained flow is widely recognized as integral to its essence, deserving of advocacy.

The First Time Fiberglass Kissed its Surface

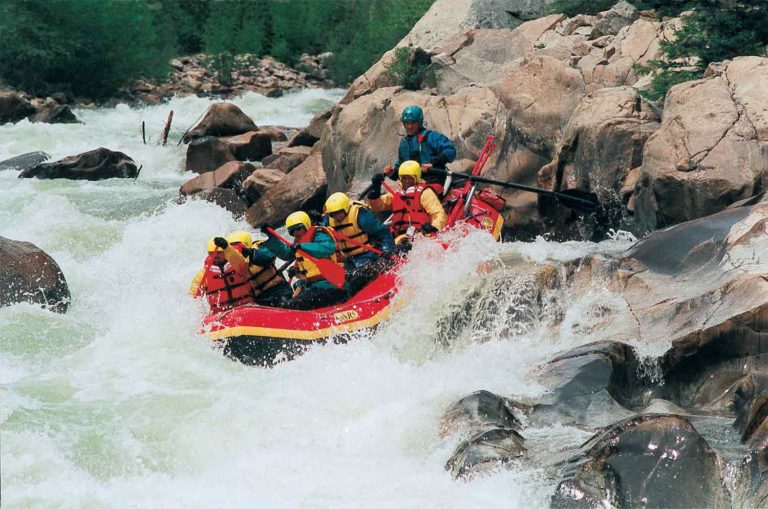

It’s not just a home to the unique ecosystems of critters; it’s a hotspot for human connection to the outdoors. Near its headwaters, the Animas is a beloved playground for rafters and kayakers.

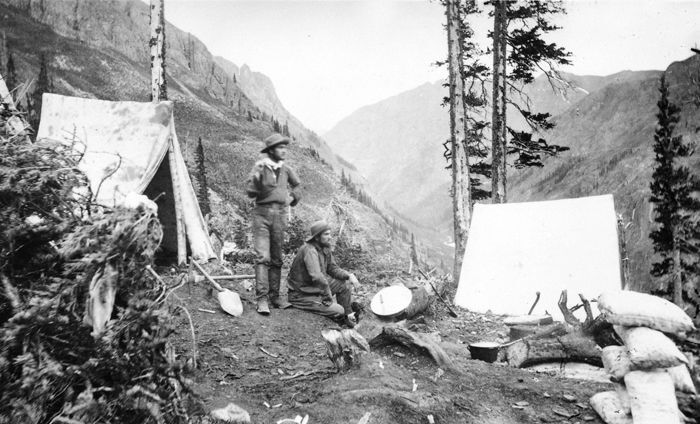

The Upper Animas River, known for its formidable rapids, seldom witnessed exploration until 1981, except for a few daring individuals clad in yellow rain suits. In that year, Wayne Walls, the owner of a commercial rafting company, charted a course by helicopter. Next, he navigated a 13-foot bucket boat through the tumultuous waters of the Upper Animas.

Alongside two companions, their goal was to demonstrate that a raft could successfully navigate the chaos of the Weminuche Wilderness—a feat they miraculously achieved (read more about the origins of rafting the Upper Animas River here).

Since then, the Upper Animas has earned the reputation of one of the most difficult commercially-run rivers in the US. The Lower Animas, conversely, supports a milder culture of life on the river, with children as young as four receiving the opportunity to strap on a helmet and a lifejacket and do a guided float alongside their family.

The River of Souls

The true essence of a soul lies in its ability to withstand physical destruction. Glacier melt, pollution, and dams have profoundly impacted the Animas River. Its ecosystems, fragile yet resilient, have weathered and overcome these forces while retaining the unbridled spirit that defines them. As we navigate its waters, may we gaze into its depths. Woven into its current are countless souls—free and unwavering.