“We in this generation must come to terms with nature, and I think we’re challenged as mankind has never been challenged before to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves.” – Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Unadulterated rivers are the magnets of life and messengers of change. Today however, a free flowing and completely uninhibited river is one of the rarest sites left of the natural world.

In the United States, just about every major waterway was reckoned for its production value nearly a century ago. As dam building quickly picked up speed in the 1930s, the West in particular was given a chance to flourish with the ample electricity and water that these new dams provided. It was time when prolonged droughts and greenhouse gases weren’t on our minds, let alone the ones of enterprising government officials.

Endeavors like the Hoover Dam were more subtle in their impact due to its sea of exaltation— a proverbial cathedral erected in the downward spiral of the Great Depression. The world-record obstacle disciplined the floods of the Colorado River and nourished desert metropolises that couldn’t thrive without it.

Today, it produces 4 times the greenhouse gas emissions of coal power plants. It also contributes to more than 600,000 acre-feet (1 acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons) of water loss through evaporation every year.

When Hoover had finally filled the ancient canyons of Lake Mead, Federal agencies had already set their eyes on yet another stretch of the Colorado River they felt worth flooding. The Grand Canyon.

Luckily, we all already know how that endeavor turned out.

And while hydropower was exchanged for life-giving flows one river after another, industrial facilities filled many of them with hazardous chemicals. In the late ’60s, unlucky rivers like the Rouge of Detroit, Buffalo of New York, and famously Cleveland’s Cuyahoga burst into flames as they drowned in sewage and industrial byproducts.

This crescendo of dilapidation in the name of human progress ignited one of the many movements of the civil rights era. It was called Environmentalism, and it came to fruition as marine biologist Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring flew off the shelves in 1962. While Carson’s book focused on chemical warfare against essential insects, it raised a profound question about humans’ relationship with the world at large.

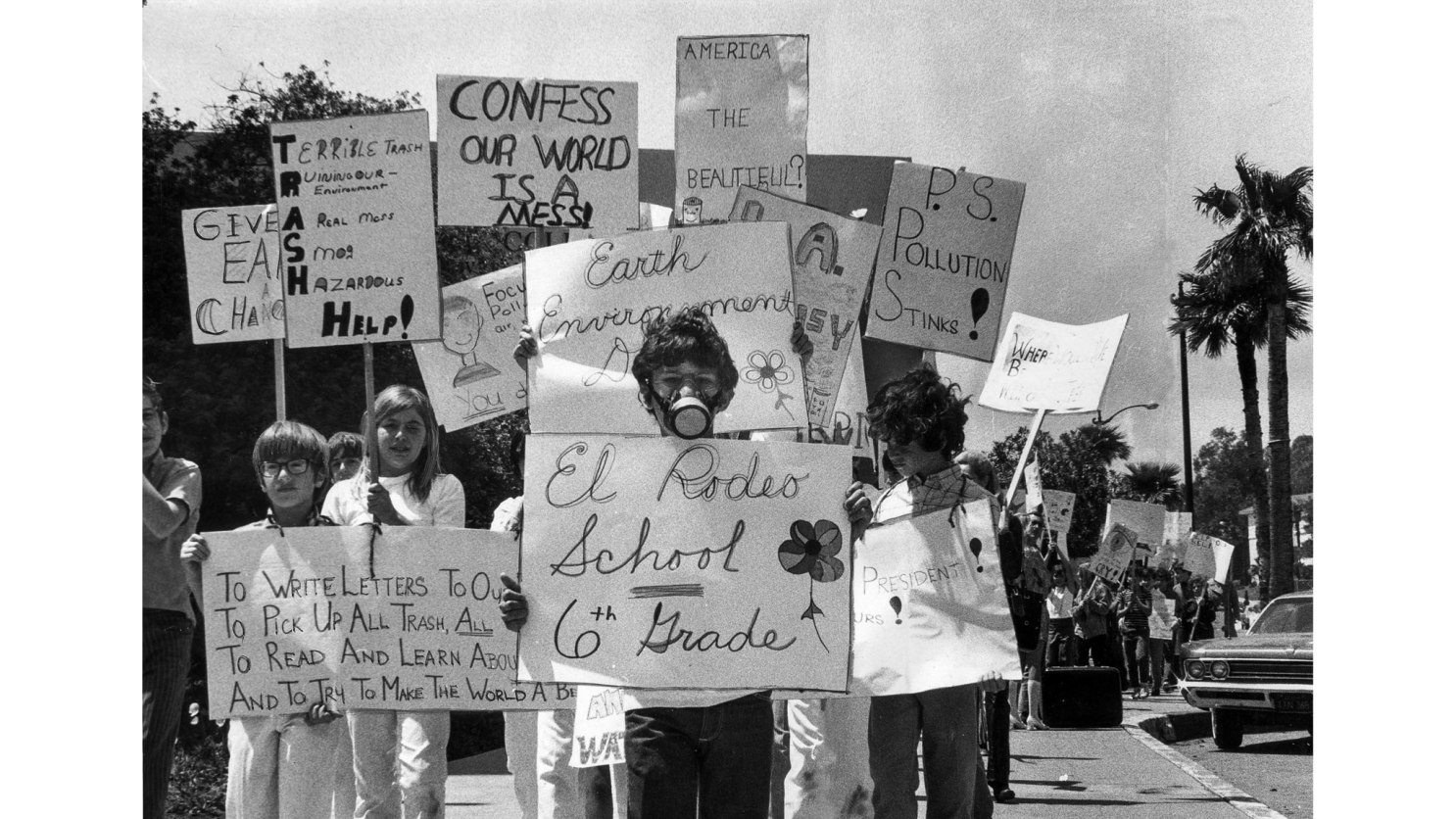

On the first Earth Day April 22, 1970, sixth graders join in the march in Los Angeles

This new wave of conservation beat the brows of deeply disturbed scientists and local communities. In their sturdiness, Congress drew up a list of statutes to hold themselves accountable for in order to prevent the exploitation of the nation’s natural resources.

As clean, quality water and air became a constitutional right along with obligations for wilderness preservation, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) became the gatekeepers of lucrative energy ventures. And with them soon came the near and dear Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

What is a Wild and Scenic River

In 1968, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was signed into law to protect rivers that “possess outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values…”

It ensures sections of raw waterways “shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

Dams, diversions, and other developments that threaten their environmental significance must be “complemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof in their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes.”

Why Should You Raft a Wild and Scenic River

#1 Wild Rivers usually Require a Raft

Rafting a Wild and Scenic River allows you to experience some of the most genuine slices of Earth you couldn’t see otherwise.

The “Wild” in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act “represent vestiges of primitive America.” Aside from riding the water itself, the only way to access truly remote rivers is by trails, which is to say if there are any at all.

A protected tributary like the Green River cuts through the largest wilderness research area in the contiguous United States. And with crumbling walls that are periodically 4,000 feet steep, strolls through this uncivilized sun-baked country should be left to the Big Horned sheep. Those who do raft through Desolation Canyon usually reach the put-in via Cessna, so there’s an idea of how remote this river actually is.

Here are some outfitters who raft some of the original Wild and Scenic Rivers designated in 1968.

Rogue River, Oregon – Momentum River Expeditions

Salmon Middle Fork, Idaho – Raft Idaho

Rio Grande, New Mexico – Los Rios River Runners

#2 They Foster Respect and Appreciation

It’s hard to advocate for the environment when you haven’t spent time with it. And our opportunities to do so are dwindling due to the rapid developments of the 20th century. To put it into perspective— Only 23% of wilderness remains on the entire planet today.

A Pew Research study in 2017 showed that 1 in 5 Americans make consistent lifestyle choices to protect the environment. The same year, a Gallup poll showed that 57% of Americans worry about pollution in rivers, lakes, and reservoirs.

Another study from 2017 showed that America’s Infrastructure Report Card received a D for dams, levees, and drinking water— grades that have yet to improve.

The newfound rarity of wild rivers makes it that more important to become acquainted with them. Seeing a healthy river in its free form is the ultimate way to appreciate its presence, and respect what it provides. The more people who raft Wild and Scenic Rivers, the greater awareness the collective will have for their vulnerability and profound significance.

#3 They Show us the Meaning of “Finite”

It’s a common morning ritual to peel oneself from the womb of warmed sheets and into a makeshift steam room. Ah, luxury in the lavatory. But the regular indulgence of a 20-minute shower uses up to 70 gallons of water. If you do that every day, that’s about 25,550 gallons a year.

In the U.S where clean water is ready at the turn of a tap, the worldwide water crisis seems more like a scary idea rather than an inevitable looming disaster.

But the nation’s dwindling water supply, especially in the West, is of growing permanence due to climate change, exponential population growth, and industries beyond needy agriculture — Although that often doesn’t help either, since southwestern states like Arizona are major producers of cotton and alfalfa. These are in the top ten of thirstiest crops, and they’re growing in a state that sees less than 13 inches of rain a year.

The average American uses around 100 gallons of water per day. That doesn’t include the products we use, such as smartphones which take almost 3,200 gallons to make, each.

When we ride the waves of a Wild and Scenic River, we can see firsthand where our water comes from. We whoop in the frigidity of an exciting spring swell and bask in the warmth of the last trickles left in late autumn. Rivers call our attention to snowcapped peaks, to the banks where its residents drink, and back to our civilizations where the water is often taken for granted.

#4 It Inspires Us to Protect Them

Time spent with any river in nature can make hearts tender. And taking away those soul-stirring places is the perfect way to break the heart completely.

The WSRA requires the Federal government to create and implement management plans to ensure a river’s promised preservation. But the follow-through of various agencies who handle WSRs is a bit like babysitting the boss.

Eight rivers in Southern California were still without management plans 8 years after their designations in 2009. The Center for Biological Diversity, a charitable organization, filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service in 2018 for neglecting to produce management plans 3 years after the deadline. They successfully settled with the agencies who are now required to produce management plans by 2024.

Organizations and local communities are often the primary instigators for designating rivers under the WRSA, just like they had to be 50 years ago. It’s a laborious practice for those who truly understand the exigency of natural places, and a constant commitment of exercising democratic discourse —and the subjection of continuously incentivized agencies.

River fanatics Frank Buono and Herm Hoops requested the WSRA designation for the very historical, deeply geologic, and dumbfoundingly scenic Green River in 1972. But the Feds didn’t hand over the 128 miles the well-educated twosome proposed.

Then in 2019, 63 miles were finally designated to Green’s flows thanks to the efforts of American Whitewater, Outdoor Alliance, Conservation Alliance, the Wilderness Society, and Utah Rivers Council.

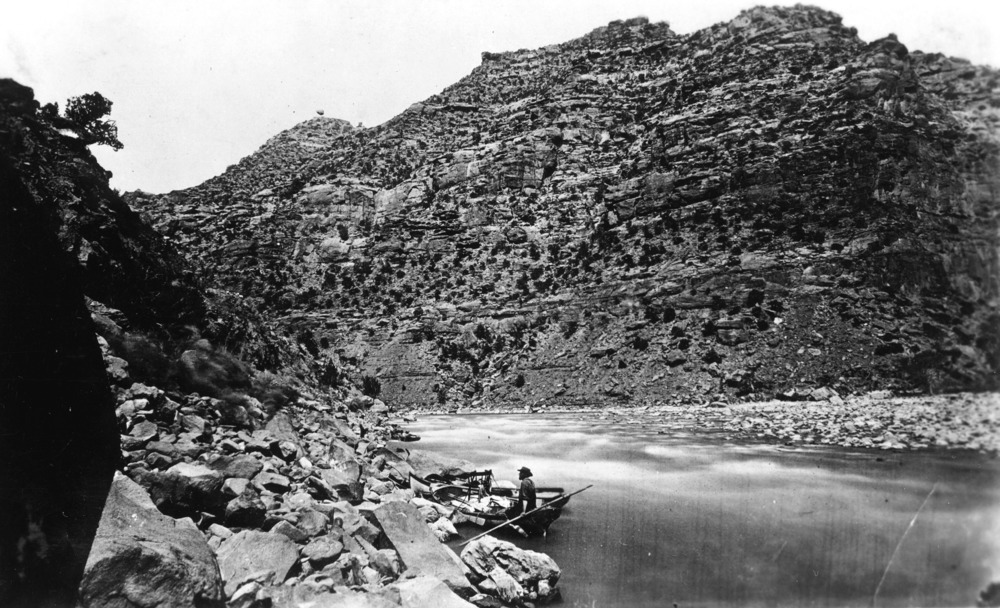

Now, stretches of the Green River through Desolation Canyon and Gray Canyon will remain innate for wild mustangs, bears, eagles, and bipeds with wooden fins. It will remain a place where dutiful river runners and fresh eyes can simultaneously sink into the past with John Welsey Powell, Butch Cassidy, and the Fremont people.

Powell’s 2nd Expedition in 1871, Desolation Canyon

Rafting a Wild and Scenic River is more than just enjoying the privilege of its beauty. It celebrates the victories of environmentists and the history of precarious exploration. When we immerse ourselves in the raw landscapes that make our lights turn on and our faucets flow, we not only broaden our awareness for the world we live in, we care about it more.

If there’s a river you want to keep clean and flowing, check out this guide for advocating for the protection of America’s waterways. And in the meantime, stay up-to-date with your local environmental management plans and make your voice heard through letters, meetings, and relentless phone calls. And get on a raft while you’re at it.

To learn more about the legendary and influential environmentalist, Herm Hoops, who helped ensure the Green River’s designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act along with other conservation victories, head over this blog that pays tribute to his foundational work in the Colorado Plateau.

More Reading

Real River Runners Write Letter — Herm Hoops and River Conservation