This article covers Herm Hoops and his role in river conservation. It is part two of our environmentalism series, find part one here.

When we ride a wild river and sink in the salubrious silence of its epic chasm, do we understand this freedom is not everyone’s prerogative? And that this privilege to see nature left in peace is the product of relentless activism?

“You run a river, you owe something back to it.” Herm Hoops always says, usually punctuated with a good “god damn it.”

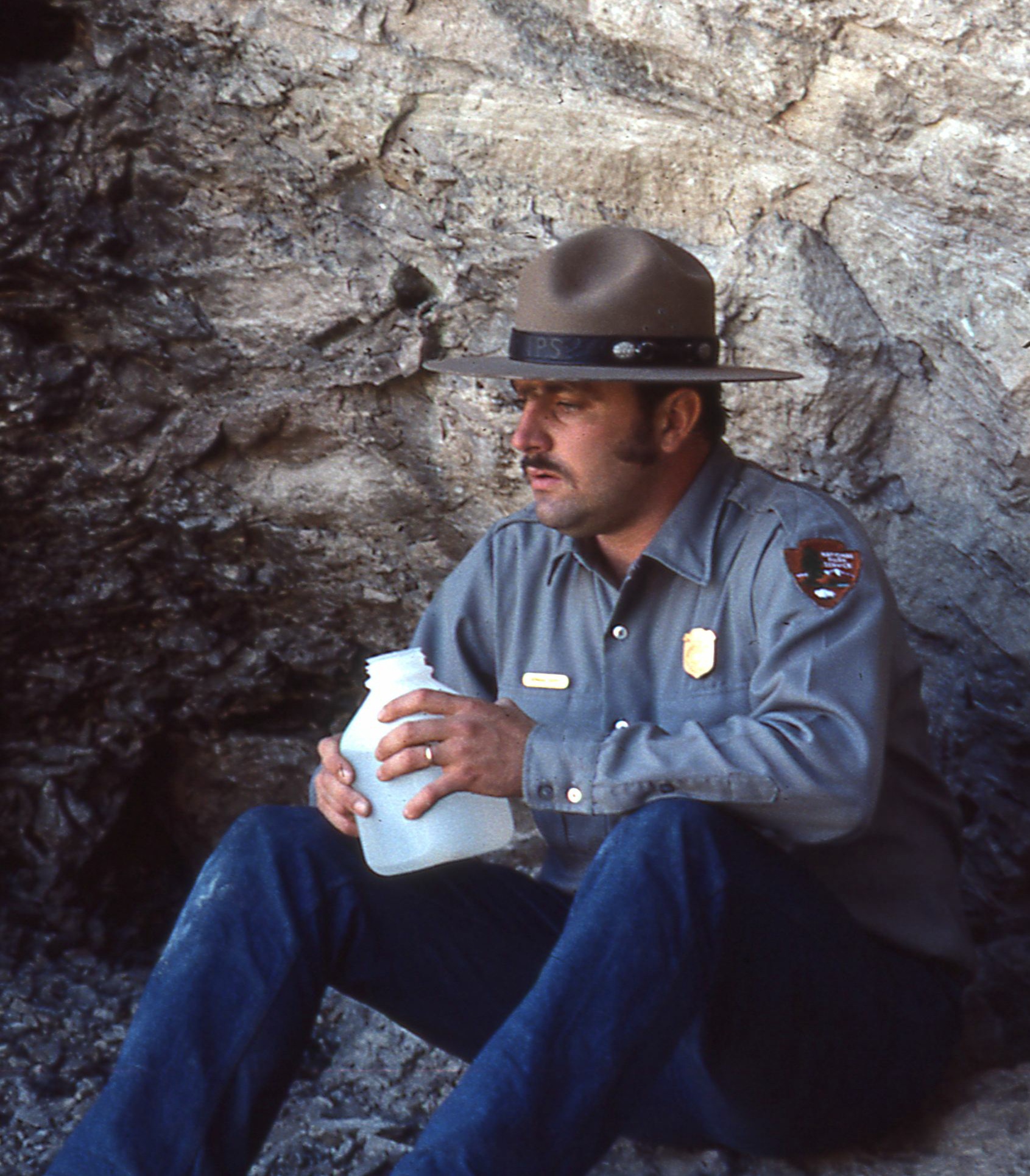

For those unfamiliar with the brassy yet personable river guide from New England— who is easily identifiable on the river from a stuffed toucan hat he stole from his son— Herm is a retired Park Service ranger, wilderness wordsmith, and among many other things, one of the most influential advocates today for western rivers.

The River Runners Hall of Fame inductee has been giving back to the West’s beloveds for five decades. From compiling the only comprehensive history of rubber rafting, to archiving the incredible contributions of Kenny Ross (a pioneer of commercial raft guiding), Herm is undoubtedly a legend of river running and environmentalism at large.

His dedication to conservation is a model for the entire river running community. It demonstrates how passive recreation will allow free flows like the Yampa and Salmon to vanish as quickly as the Dolores and Glen Canyon.

In Herm’s journal from his last Desolation Canyon trip, he wrote, “…real river runners don’t wear cool t-shirts, they write letters!”

East to West

Herm headed west for the Snake River in 1966 with a rubberized canvass raft. This was prompted after he saw a special on rafting in the Grand Canyon— where he’d quickly make a name for himself years later.

He had years of experience rowing canoes prior to this trip. It just happened to be in Vermont, on his family’s farm, on a pond.

Below the jagged, novelesque snowcaps of Grand Teton National Park, he approached the fishermen lined banks with a couple of friends and his craft. It was a day like many first-timers. Frustration twirled him as much as the boat. Nerves rippled through him as the first rock grabbed at his yellow balloon of a magic carpet.

“I was afraid it was gonna blow up.”

It did not. And as the 20-year-old paddled past oar boats of black and silver, he would bring himself back to the same stretch the next day, infatuated with the challenges and culture of running a river.

This turned a new chapter for Herm. One where he was rafting as many waterways as possible, regardless if getting back to his car took more than a week after take out.

Becoming an Activist

Herm taught high school agriculture in Vermont after college. But after five years of knowing that progress doesn’t always align with keeping a grade book, he decided to move out of the classroom and basically into his raft.

Herm made his acquaintance with Dinosaur National Monument in 1971, a geologic dreamscape rising between two ancient rivers in crimson and cream.

There he met Frank Buono, a ranger in Echo Park, who quickly became a friend and fellow “outlaw” for upholding the rowdy spirit of canyon culture. The following winter, Frank bought property close to Hoops in Vermont where they worked together building their cabins.

There, conservation would plant itself into Herm’s paradigm. But it didn’t necessarily come without some unexpected, external motivation.

As a connoisseur of canyon literature, Herm had started writing a book about whitewater rafting— a lucrative opportunity he saw in a genre yet to flourish. Ready for thoughts on a bestseller in the making, he mailed off more than a hundred letters to a swath of outfitters across the West.

And feedback did he receive, particularly from an Oregon guide who reproached the book’s self-serving nature.

“Oh I got angry,” seemingly as the notes promptly met the potbelly stove. “But after two or three weeks of thinking about it, I realized that he was right and that I did have a responsibility. If I’m going to use these rivers, I need to find out what’s going on. And I slowly decided to not be involved with rivers in Vermont, or Oregon or Montana or Idaho, but to be focused on the Colorado River system.”

In the midst of concentrating his efforts— and abandoning the novel— Herm took on his first role as an activist. It was certainly headfirst as he joined the colossal opposition of the James Bay Project.

When initiated in 1971, James Bay was one of the largest hydro-electric and environmental engineering endeavors in history. The eight dams destroyed traditional hunting and sacred lands of the Cree and Inuit, drowned over 10,000 caribou, and poisoned marine life with mercury.

Designating Desolation Canyon

Still in those logs, Herm and Frank would throw around rivers they thought should have additional protection. Naturally, the Green River’s breadth through Desolation Canyon became their conquest. In 1972, they submitted their plan to the Department of Interior for Deso’s national monument status.

The 100 million-year-old crack splinters through the largest wilderness research area in the lower 48. It’s a crumbling cathedral where roads are seldom and wild horses are not. The cliffs soar higher than the Grand Canyon’s in certain stretches, and the scenery is as dumbfounding as the dance Big Horned sheep perform across its walls.

“After about three months, the letter came back saying the Park Service has already studied that area and has found it unsuitable for national monument status,” he said.

But in 2019, a collective joined Hoops to ensure its preservation. American Whitewater, Outdoor Alliance, Conservation Alliance, the Wilderness Society, and Utah Rivers Council helped successfully designate 63 miles of Desolation Canyon under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act with several adjacent Wilderness areas.

Taking half a century to legitimize Desolation’s significance was a battle where most would have thrown in the sponge. But Herm is the kind of man who runs “follow the ice out” trips in this rift, even after having to walk 50 miles to Myton from one, or fighting off hypothermia on another.

“I did it because it was the right thing to do. I couldn’t understand why everybody couldn’t do that.”

Let the River Runner through it

Herm has deemed his greatest environmental accomplishment as the Tusher Diversion. This recent rehabilitation project mended the Green River’s only major obstruction from Flaming Gorge to Lake Powell.

A few miles north of the town of Green River, the irrigation installment sits across from an audience of bluffs watching over clumps of crop circles.

With more dams today than not in the Colorado Plateau, this is an obliging passage that allows those with the time and tenacity to mimic Powell’s 150 year-old expedition. Rafters on this 500 mile drift can give thanks to Hoop’s knowledge United States v. Utah, which ensured the Green River would remain navigable from Swasey’s rapid to the Colorado River.

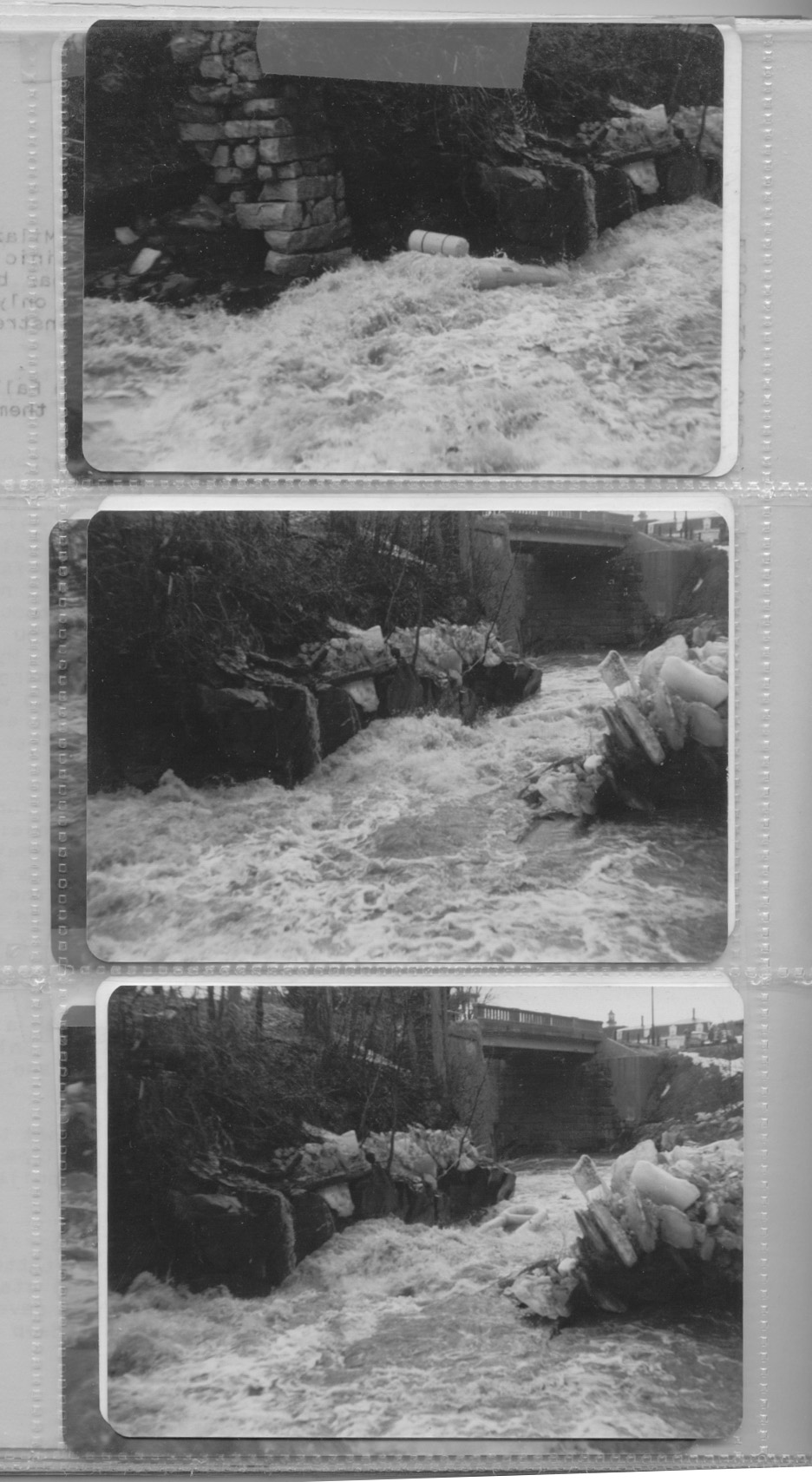

It was seemingly upheld, until the dam began circulating into a doozy due to alleged flood damage in 2011.

“I knew that they wanted to rebuild that diversion, and I’d run it a bunch of times. There was rebar sticking up that was really dangerous and keeper hydraulics at certain water levels. And so I became involved,” Herm said. “I laid onto the development committee the fact that this was a federally designated navigable waterway, and they could not legally stop river navigation.”

Oars in the water, he partnered with Nathan Fey from American Whitewater to acquire the engineering and Utah State Park ranger Brody Young for the funds to build it.

Their attentive involvement with the Natural Resources Conservation Service who oversaw the project eventually led to the intended result; A safe passage for boats and fish. The $7.7 million dollar project started construction in 2015 and finished in the summer of 2017.

Water and Oil

Other efforts to “Stop the fatheads who turn the wheels of civilization,” as Herm would say are often up against the extraction of Utah’s ancient seabeds.

Living in Jensen where the astounding Tavaputs meets the majority of Utah’s pump jacks, Herm is a fish out of shale. Or tree hugger according to his neighboring Vernalians.

“The question is not whether we need oil & gas. The question is whether we need that little bit of oil & gas INSTEAD of a few beautiful, quiet, and wild places to get away to, to think and refresh our soul, to hike, float or camp? But can’t we leave a few areas?” A notion he’s repeatedly expressed in and out of city hall meetings.

And while one might think private river runners would be on the same page as Herm, some actually favor oil and gas developments he said. The reasons range from appreciating the improved roads out to Deso’s Sand Wash boat ramp to wanting cheap diesel.

This was especially evident in his conservation efforts that proposed the removal of dead pump jacks and unused power lines, road access, required noise control, as well as directional drilling on new leases along the White River.

“It just went nowhere. And I couldn’t believe it because it wasn’t about taking anything away from anybody. It was a great opportunity to show that conservationists, bikers, ATVers, ranchers, the extractive industry, local, state and federal governments could work together toward a long-range common goal.”

The Earth’s Future Caretakers

“If you want to change attitudes, you have to involve people when they’re very young and teach them to love something and to understand something.”

For Herm, a visit to Yellowstone in 1957 left the 11-year-old dumbstruck by the far-reaching wilderness swept before him.

“It triggered something that I didn’t even recognize at the time,” he said.

When he became the Environmental Education Specialist in Cape Hatteras in North Carolina, he bought stacks of boogie boards so visitors young and old could appreciate the power of the ocean.

As a ranger in Gateway National Recreation Area on Staten Island, he helped facilitate the first camping experiences of young New Yorkers.

In Dinosaur through the Kids Hut programs, he sent flocks of 4th, 5th and 6th graders tubing from the Split Mountain Boat Ramp to the Green River Campground. It showed them firsthand how eddies collected dinosaur bones through the epochs.

Years after he retired from Dinosaur National Monument, Herm took a turn on the Desert Voices Nature Trail above Echo Park. The path is adorned with leaning monoliths and interpretive signs made “for kids by kids” from a program he’d started decades ago. On his way up he met a family on their way down, he asked about their hike.

“It turns out this guy was an oil field worker who had gone to the Kids Hut, and he was bringing his kids to show them the sign that he made,” he said. “So, there was something there.”

Herm’s Advice

Herm is a walking library stockpiled with environmental laws and regulations, even down to the enforceable speed limits in Split Mountain. This has allowed him to advocate strategically while writing letters until his fingers bled— perhaps literally.

“It takes a lot of digging into things that people don’t like to read. And frankly, once you get into it it’s pretty fascinating.”

But for those who aren’t as disciplined or patient with the vernacular of legislation, Herm has stepped in with more than a few handfuls of organizations and outfitters to help them fight for the Southwest’s last slices of wilderness. He composes digestible papers on statutes, holds seminars, and runs a constant chain of communication about environmental threats through his emailing list.

To keep up the laborious work required of activists, continue writing and calling Congress, he says. Write letters citing law as it will demand their attention, and send those letters out even when conservation concerns haven’t presented themselves.

According to the river whisperer, waterways that are in need of attention now include the serene White River in Utah, the capricious Salt River in Arizona, the very dry Dolores in Colorado, Colorado’s historic Escalante Canyon, multiple rivers under current threats Alaska, and the permit-free Ouray to Sandwash section on the Green River.

Take Out

In September of 2018 Herm took his last run in Desolation Canyon. The indelible archive has greeted him over a hundred times with sun, snow, and oftentimes alone as he prefers.

He rowed the trip along with five oxygen tanks and a lawnmower battery to keep them flowing. Along with him was his wife Val, Rig to Flip filmmakers Ben, Whitney, Mitch, Cody, and plenty of ceremonious nourishments of donuts and precooked bacon. This journey presented by NRS can— and should better yet— be watched on their website here.

It was a culmination of Herm’s adventures and devotion to the places that perpetually brought him solitude. It was a more than difficult goodbye to the beaches, rapids, petroglyphs, homesteads, side canyons, and amphitheaters that know Herm well.

In one of Herm’s journals from a solo trip he took down Deso in April of 2015, he recounted a thought he’d deeply drifted into as his boat drifted deeper in the rift.

“If people lack vision, if they have not experienced a place they will not love it. If they don’t love it they will not rise up and demand that it is protected from threats or intrusion… The generation of visionaries like Martin Litton, Dee Holladay, Don and Ted Hatch, of David Brower and Howard Zahniser are gone. Who will take their place?”

While the waters that have been good to Herm may not greet him and his Toucan again, his vigorous work to reciprocate that goodness continues. And to the river loving people who continue to flow freely, his advice from his last trip’s journal deems their obligations with eloquence;

“I have spent 72 years trying to save places for my grandchildren and their grandchildren in order that they have that future and so they can experience the natural world somewhat as I did. We need to understand that we can lose everything through “a thousand cuts” or gigantic projects because well-meaning people stayed silent. What can they do? These days it is hard, but a river begins with a tiny trickle from the rocks at its headwaters.”

More Reading

Rafting a Wild and Scenic River – How it Saves a Piece of Nature