Thousands of feet above the unending desert of Utah’s armpit, one may wonder if they’ve been pranked by the pilot. Plains of dusted nothing sprawl out in a sea of brown, making soaring passengers question where exactly the journey begins. Then suddenly, a stampede of mesas and ravines begin to rise from the sunbaked loam, giving passengers a small taste of what’s to come— maybe a place not so desolate.

The Green River flows down from Wyoming through canyons coated in alpine to wide open desolation once creeping into Utah. Here, it greets the bird’s eye view with growing plateaus which bow to the river banks on either side. After landing in a plane on what can barely be considered a runway, feet meet the mesa’s edge for a dwarfing panorama; a scene many have witnessed from two dimensional paintings of the wild West.

An ever-growing canyon waits in loom. Desolation Canyon reserves a wealth of geology and history within its thousands of feet of sliced sediment. For the next 86 miles, the past unravels without hesitation. Some stories go back less than a century, while others are so removed from an era long since passed, we’d need fossils to believe them.

Mahogany Shale

Throughout Desolation, pockets of black substance seep like spilled ink from the powdery walls. It’s a lucrative remembrance of a lively lakebed from 50 million years ago.

At that time, dinosaurs were out and mammals were in, thriving here due to a freshwater basin named Lake Uinta. It was in the heart of the Eocene Epoch, when Utah sported dense humid forests that resembled today’s Louisiana. The lake covered nearly a fourth of the state, leaving behind immaculate fossils hidden in shale chips. Fern sprigs and garfish (which still swim in the Mississippi River) are among the artifacts to keep an eye out for in this area.

Before the climate cooled and the basin faded in drought around 33 million years ago, algae, familiar fish, and marine reptiles contributed their bodies to the lake floor. As the pressure of clay, sand, and more bodies stacked themselves atop the basin’s bottom, it transformed them into the natural compound kerogen. With more pressure, heat, and time, kerogen eventually evolved into oil and gas.

Ninety percent of Utah’s oil and gas wells are in the northwestern region where the Uintah Basin rested. As of 2018, it hosts 30,000 active well sites and nearly 100,000 abandoned sites. Combined, these well pads are about the size of Massachusetts.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) oversees 290,845 acres of Desolation Canyon, making it the government’s largest wilderness study area in the lower 48. The BLM approved 807 wells with the West Tavaputs Environmental Impact Statement in 2010. Only around 20 active sites are operating as of 2019.

Tavaputs Plateau

John Wesley Powell, who traversed this rift in 1869, named the massive plateau after a Uintah chief. Tavaputs in Ute translates to the sunrise on canyon walls.

Some stretches in Desolation Canyon are over 5,000 feet steep. At times they dive deeper than the Grand Canyon’s average of 4,000 feet throughout its chisel.

Colossal escarpments crumble from Tavaputs Plateau, which has been sliced into western and eastern regions by the Green River. The Tavaputs have been a working progress since 100 million years ago. They were deposited as the continents spread, dinosaurs enjoyed their last epoch, and plants blossomed Earth’s first flowers.

During this time, North America was split into two humongous islands by the Western Interior Seaway. Today, we can see Utah’s coastal period in the form of the tremendous Book Cliffs.

Atop the Book Cliffs, the Roan Plateau ascends another few thousand feet. The Roan Cliffs were deposited only 65–30 million years ago when the sea had retreated into large basins.

The Green River exposes these layers stuffed with fossilized marine life. Further down the drift, Desolation Canyon ends and Gray Canyon begins. In this drastic change of scenery, the more mature rocks of the Tavaputs Plateau rise from their Cretaceous Epoch.

Sumner’s Amphitheater

“The escarpments formed by the cut edges of the rock are often vertical, sometimes terraced, and in some places the treads of the terraces are sloping. In the quiet curves, vast amphitheaters are formed, now in vertical rocks, now in steps.” Powell’s journal, July 7th, 1869.

This unique auditorium soars with symmetrical dexterity, displaying itself early into the trip. Its neatly mirrored erosion could be from weathering on the hinge of an anticline. This entails the formation being on the top of folds, which resemble waves in rock layers when they’ve endured long and steady pressure. On these folds, harder rock layers resist weathering better than the surrounding softer layers. It may have created the stadium effect of the structure that dipped out from delicate rock.

Another possibility is that this vast structure is a piece of a tilted bed, and it’s showing off a cross section that has been heavily eroded. Or, it could be the product of spheroidal weathering from jointed bedrock. Imagine an onion, and you make a few slices in it halfway through. It’s tear-jerking layers can now peel off in separate sections, but still at an even rate. While this type of weathering usually happens on smaller scales, it could be a potential explanation for Sumner’s uniform deterioration.

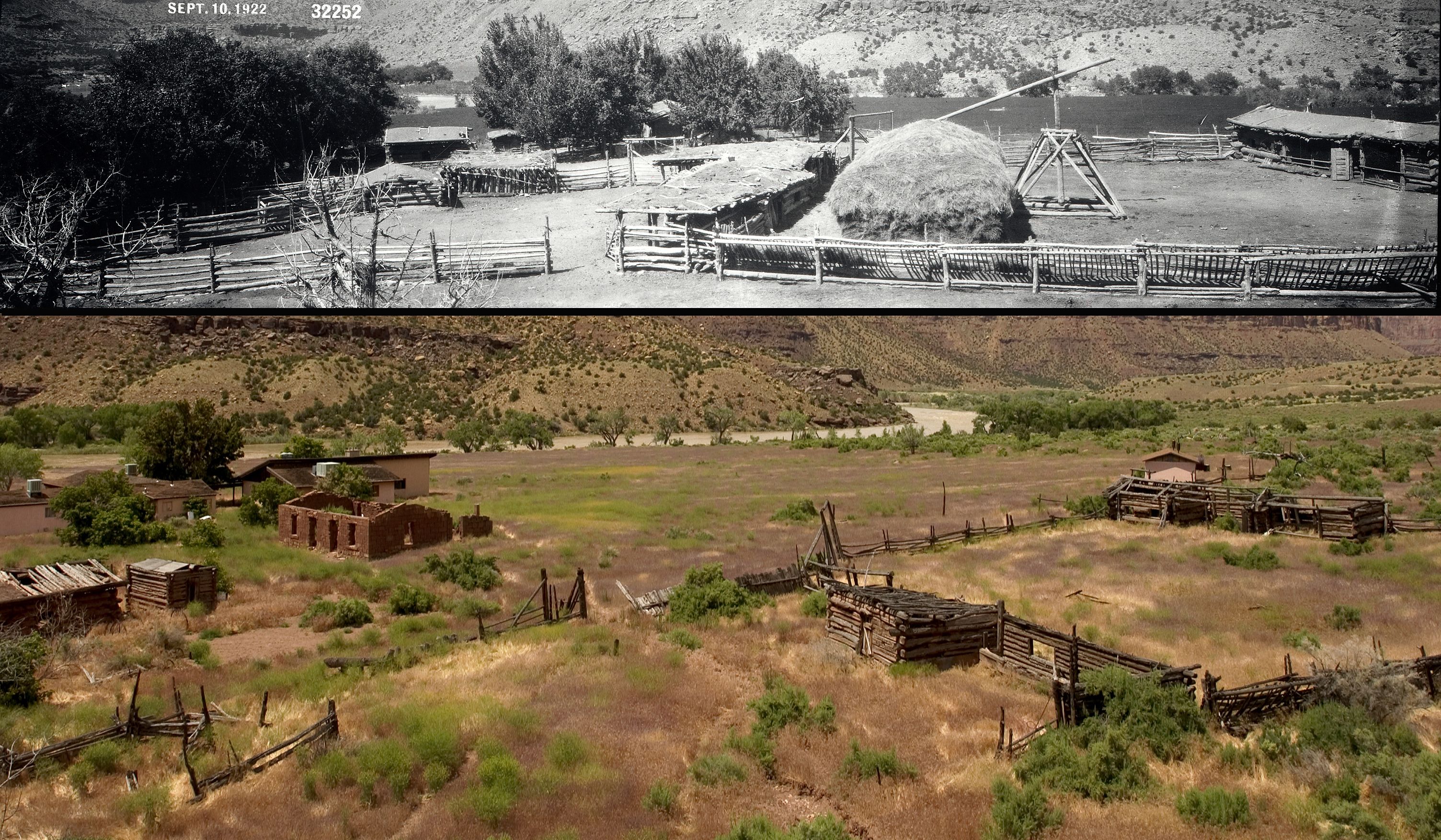

Sites at Rock Creek and Coal Creek

Among the abandoned ranches scattered throughout Desolation, one of impressively sound construction is the Seamount homestead, where cabins still stand amongst cottonwoods and willows just up Rock Creek.

In 1913, brothers Alfred, Dan, and Bill Seamount ventured down the steep walls—horses carrying all necessities from plows to sugar. In the heart of Desolation, the cattle ranch operated off and on until the 1960’s. The apple orchard still blooms, and remnants that haven’t been taken as keepsakes can still be discovered throughout the property. Descendants of the Seamounts still gather here for family reunions during the summer.

Just before the Seamounts’ founded their homestead, construction of the Buell Dam began just down river in 1911. The dam was intended for irrigation and energy with hopes to provide for 50 thousand households.

But the project fell through in failure to foot its 10 million dollar bill. By 1921, the dam was a lost cause. Another dam named Rattlesnake was intended to flood Gray Canyon in the 1950s, but the same problems arose due to the isolated nature of these incredible crevices. Today, one can still discover cabins and tools from the dam workers with a short hike up Coal Creek.

Homesteaders and Outlaws

David McPherson started ranching with his family up Florence Creek in 1889. Dave originally journeyed West to work on steam engines for the railroad. During this time, he became enamored with this remote wilderness after reading a copy of John Wesley Powell’s The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons. Spry and inspired, he loaded mules and horses with all the ranching equipment that fit, completely disassembled to bolts and all. Without a single road to guide him, he and his family shimmied their way down into Desolation to start life anew.

David’s son, Jim, took over the ranch after his father’s death in 1909. With still no road, Jim brought in purebred British beef cattle along with an organ for the family’s enjoyment. Jim also hired multiple school teachers and hiked them down to the ranch to tutor his five children as they lived in the canyon year-round.

The McPherson homestead sat right along the path of the Outlaw Trail. While “trail” is a bit of an overstatement, it was used by historically successful robbers Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch. According to Jim, the vigilantes would visit off and on to hideout after robberies and trade horses—animals that were most-likely stolen from other neighboring homesteads along the Green River.

Jet-effect Wind

“At night we camp on a sandy beach. The wind blows a hurricane; the drifting sand almost blinds us; and nowhere can we find shelter. The wind continues to blow all night, the sand sifting through our blankets and piling over us until we are covered as in a snowdrift. We are glad when morning comes.” Powell’s journal, July 12, 1869

Steep, narrow rifts like Desolation make for incredible projectile breezes. By late afternoon, the top of the Tavaputs Plateau begins its evening chill at 9,000 feet. This brisk, heavy draft begins to flirt with the warmer air that had been rising from the canyon all day.

Precipitous slopes make this exchange of hot to cold confined, quick and turbulent. With currents that whip (sometimes up to 70 mph), its jet-effect winds can be attributed to Desolation’s plunging passages. These winds help carve the abstract hoodoos, spires, arches and crags throughout this phenomenal drift.

Fremont People

There are around 75 discovered archaeological sites throughout Desolation canyon. They were left by the Fremont people who lived throughout the Southwest around 2,000 years ago. In 2006, Desolation Canyon saw its first archaeological expedition to document these sites and manage them for protection.

Large panels of Fremont rock art can still be found throughout Desolation right off the river in Jack’s Creek on Mushroom Rock, Cottonwood Canyon, and Flat Canyon. The geometric scenes often show adorned human figures alongside crops and native animals. These carved illustrations, along with few preserved relics and granaries, give us a window into how the people in this canyon before us survived the parched landscape long before the advent of modern comforts.

Archeologists named the Fremont people after the Fremont River in southwestern Utah. Ironically, the Fremont River was named after John Charles Fremont, an American military officer, map maker and politician who traveled alongside Kit Carson massacring Native Americans throughout their explorations in the 19th century.

Gunnison Butte

As the float continues deeper into Earth’s crust and nears the journey’s end, Gray Canyon emerges from 145 million years ago. The spire of Gunnison Butte is poised like an ancient watchtower observing the Green River’s exhibitions through countless millennia. Outcrops like this find their silhouettes after cracks in the solid structure widen and crumble to wind and water.

This geologic site, along with others throughout Utah, was named after John W. Gunnison. The U.S military captain was sent West to survey potential routes for the transcontinental railroad in 1853. When he and his troops made it to the Mormon-established town of Salt Lake City, Gunnison impressively smooth-talked indigenous tribes into peaceful agreements.

Confident that he and his squad could continue to earn themselves safety, Gunnison and his guys ventured into the wilderness of western Utah. When they reached the Sevier River, they were promptly murdered their first night in camp. The killings were attributed presumably to the Paiute tribe; an indigenous group who resisted Mormon settlements throughout Utah in the 19th century.

One account claimed the men were actually killed by a mob of Latter Day Saints known as Danites who had somehow disguised themselves as Paiutes. At a time when the Mormon prophet Brigham Young governed the Utah territory, the speculation was never investigated.

From above, or standing at the entrance to this rugged chasm, many find the sheer amount of history, views, and rock residing in Desolation Canyon astounding. The canyon provides humans with new-found information about the planet’s past lives, as well as continually blows our minds as to how one could ever traverse its walls without fatality. The entire experience continuously conquers human rendering in its remoteness. In a place that seems so removed from hospitality, it demands our curiosity, beckoning us to go deeper and deeper into its ancient ravine.

More Reading:

History and Geology of the Yampa River: A Past of Keeping it Wild

Six Reasons to Take Your Family on a Multi-Day Raft Trip

Rocks You Need to See – The Amazing Geology in Cataract Canyon