What does the desert bighorn say? “Bleat, bleat, baa, baa, snort” finished with a cactus stab or headbutt. Or something like that when the horns get involved. There’s also probably a lot of climber jargon, which honestly is harder to understand than bleats and baas.

But even if we can’t converse with bighorns— like what’s more fun to watch via cliffside over a river? A raft flip in a rapid, or peregrine falcon dive into said rapid?— There’s still plenty to be learned about this acrobat of the desert.

Read on for little facts about big, bad, Desert Bighorn Sheep!

Where did Bighorn Sheep Come From?

Bighorns are mighty descendents of the Siberian Snow Sheep. This epically-named sheep waltzed across the land bridge of the Bering Strait from today’s Russia into Alaska around 750,000 years ago. It also came with plenty of other creatures (including the grizzly bear, moose, antelope, mammoth, and people) that were added to North America’s huge menu of species, per Live Science.

During this time, sea levels were low enough to expose this valley that connected the continents. But around 10,000 years ago, climate change melted the glaciers, and the Chukchi Sea now covers all but a few islands of the land bridge, per NPS.

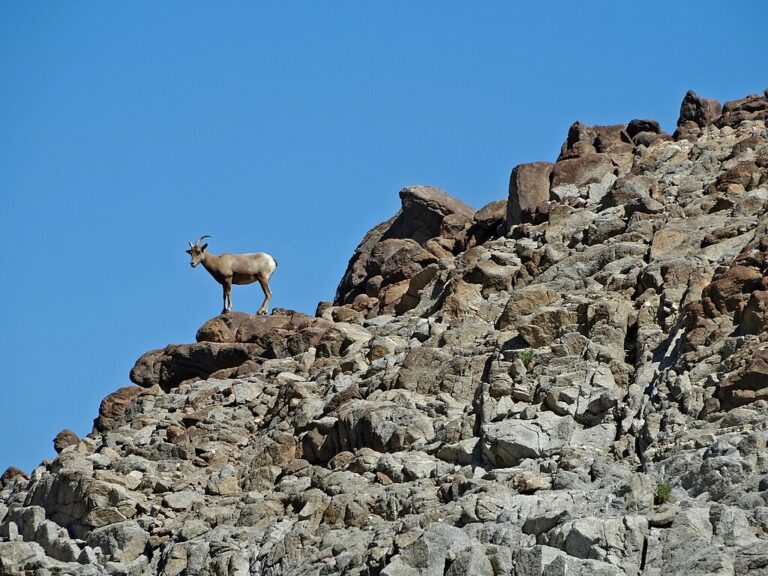

Three types of bighorns now roam across North America; the Sierra Nevada, Rocky Mountain, and Desert. Desert bighorn sheep are understandably adapted to their environments, and look a little different from their alpine cousins by sporting smaller bodies, light-colored coats, and longer legs for doing parkour around the canyons they call home, per NPS.

At one time there was another subspecies called the Audubon Bighorn, which used to roam the Great Plains. But as whites moved into the region, they were extinct by the early 1900s. This was nearly the fate for Desert Bighorns, as colonizers brought diseases with their European livestock, along with uneducated hunting practices in delicate desert ecosystems. By 1975, there were only 1,000 bighorns left in Utah.

One Herd in Canyonlands Helped Save Utah’s Population

As the Desert Bighorn was facing extinction in the 1970s, government agencies stepped in to help the herds. There was a mighty bunch of 100 in Canyonlands National Park, which was used to help repopulate other areas along the Colorado River like in Arches National Park.

Luckily the herds thrived. Within a couple decades, over 600 bighorns were grazing the Utah desert, chomping on just about everything from barrel cactus to crunchy sage brush, yum. Within the last 10 years, biologists have recorded over 3,000 in the state. But due to the animal’s sensitivity to disease carried by livestock sheep and goats, like pneumonia and Orf, even restricted hunting practices aren’t always enough to protect them.

To help the Desert Bighorn thrive, constant management will most likely be needed as humans and other animals keep them susceptible to surviving in already harsh environments, per NPS. Fortunately, the bighorns of Canyonlands will always be protected from hunting and exposure to domestic animals. They can often be seen on river trips through the park in Cataract Canyon, or Salt Creek Canyon in the Needles District, which is quite the treat for such an elusive animal.

What’s the Rut all About?

If you’ve ever wondered why males are called rams, mating season will definitely spell it out. Just like most of the guys in the animal kingdom, bighorn sheep have to prove their worth to reproduce to an audience of apathetic girls. This is carried out with good old fashioned, repeated head slamming. And they’ve got to make it count, since rams and ewes only come together during the rut season in the fall.

Desert bighorns can collide with a force three times their body weight, averaging about 600 pounds. Their horns typically max out around 30 pounds, which seems a little light with the previous pounds of pressure mentioned. But these big showy headpieces have a very unique design that is latticed and gapped, providing an exclusive shock-absorbing technology only found in Bighorns.

This is why rams don’t get an immediate concussion after one skull-rattling rut— which would probably happen if their horns were totally solid, and then by golly nobody’s got a lamb on the way. It’s not just a bunch of dense keratin either which are what fingernails are made of. The very inner layer of the horn contains blood vessels that help these sheep regulate their body temperature in harsh weather conditions.

The structure of these horns have led engineers to study them for all impact-related technologies, from crash testing cars to better running shoes, per Bucknell University.

What is the Bighorn’s Significance to Indigenous People?

If you’ve ever explored the wild deserts of Utah, be it through grand river corridors like Desolation and Cataract Canyon, or havens like Bears Ears National Monument, the significance of bighorn sheep is an inevitable discovery.

Countless petroglyphs throughout the region depict herds and hunting scenes, along with human figures that seem to wear the horns. Bighorn sheep were a main source for food, clothing, tools, artwork and weapons for indigenous people of the West. It continues to be held sacred across western tribes, as they continue to hunt and use the animal for multiple purposes like their ancestors.

Since statehood began picking up in the West in the late 1800s, honoring agreements for hunting rights (among many others) has been an ongoing struggle for Native people. Fortunately in 2008, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe updated a 135-year-old contract with Colorado known as the Brunot Agreement.

The “Memorandum of Understanding” ensures that the Tribe not only can continue to exercise their inherent hunting rights in the San Juan Mountains, but also that the U.S government implements the Utes’ long-term practices of wildlife conservation.

Hooves that Quite Behoove

If you’ve ever watched a bighorn sheep bound along the side of a cliff on the most miniscule of ledges, with the grace of gymnast and devil-may-care chutzpah, you’ve probably uttered some sentiment along the lines of, “How in the fu-llet mignon are they doing that?” And our response would be, these aren’t your grandma’s horse’s hooves. Because that makes perfect sense.

Bighorn sheep have an inner layer to their hooves that resembles the spongy, grippy texture of an erasure, while the outer layer is hard. The hoof is also divided into two “toes”, which also allow them more gripping power, and the ability to run on a lip that’s 2 inches wide.

Without this design, it would be impossible for them to balance on nonexistent nubs while mountain lions pout below the precipice. This is a common practice for new mothers, who will often keep their lambs in these extremely exposed areas for days at a time to avoid predators, per National Bighorn Sheep Center. Now that’s what we call learning by trial and error, just… with no error allowed.

FAST FACTS:

How fast can bighorn sheep run?

30 mph, per NPS.

How long do Desert Bighorns usually live?

Females can live 10-14 years, and Males 9-13 years.

How long can Desert Bighorns go without water?

Outside of summer, they can go MONTHS without drinking water, and can stand to lose 30% of their fluid body weight before getting dehydrated, per Bighorn Institute. Most animals can only handle losing 10%. This is because the desert bighorn diet includes natural electrolytes, like those in barrel cactus.

What do I do if I see a Bighorn Sheep?

If you’re lucky enough to see one up close, quietly congratulate yourself and respect its space. If you come across a ram, don’t make eye contact, move away and try to get to lower ground.

Where can you find Desert Bighorn Sheep?

Wilderness canyons near water sources in Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Rafting trips in Cataract Canyon, Desolation Canyon, Yampa River and Gates of Lodore commonly get to see these majestic animals on the canyon walls and sipping along the riverbanks.

More Reading