Telluride‘s past is much like its mountains. There was unbelievable beauty and balance, juxtaposed by the harsh bite of change, not unlike an unwelcome and commonly early winter. But as we all know change is inevitable in the alpine, especially when people get involved.

It is an understatement to say that this corner of Colorado has been To-Hell-You-Ride and back. From its status as an ancient haven for indigenous hunters, to becoming a status symbol in and of itself, Telluride‘s evolution has been as dramatic as the summits that surround it.

Between the flow of protecting its natural beauty and the ebb of enterprising it, read on to learn about Telluride‘s transformation.

Before it was Telluride

“The Utes believed that they didn’t own the land, but that the land owned them.” per Southern Ute Nation.

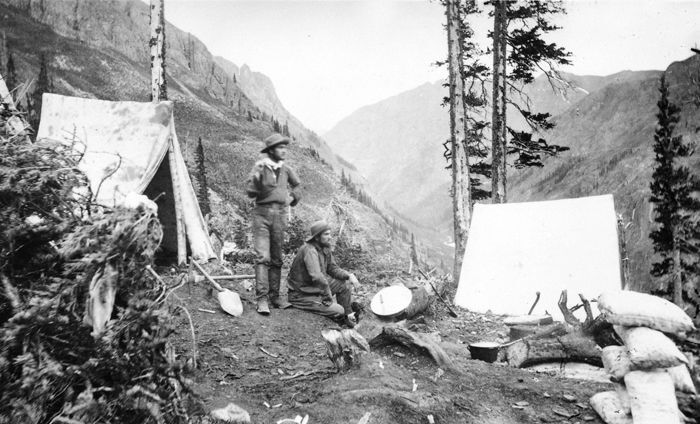

Before the mid 1800s, this box canyon— along with the rest of Colorado— was indelibly pristine. The only alterations it saw were the temporary hunting camps of the Nuuchu, renamed Ute by Spanish explorers.

For over 700 years, the Rocky Mountains and beyond were home to various bands of the Ute. The band that frequented the area was the Tabeguache (pronounced tab-uh-wash), although all 7 bands intermingled as they moved between the mountains.

This culture was (and still is) dedicated to balance with the environment, attuning to nature’s rhythm to not over harvest for game or plants. It kept their lifestyle semi-nomadic to allow for periods of replenishment, so they undulated between the cool alpine in spring and high deserts in winter.

Their existence and Creation Story was heavily influenced by the land, with many legends of the Coyote, Bear and Lion. And as master equestrians and traders since the 15th century, the Utes were a dynamic entity that avidly safeguarded this sacred landscape for centuries.

Despite the encroachment of white settlers, they were able to maintain mostly peaceful relationships into the 19th century. But in 1849, the paradigm of man owning land overpowered the Utes’ long way of life.

The nation was forced to sign a Treaty to recognize the United States as a sovereign nation, creating new imaginary boundaries of Ute land, per Southern Ute Nation. This treaty would be the first of many that would eventually push the Utes out the Rockies, and into the small reservations in Colorado and Utah we know today, per Colorado Encyclopedia.

The Boom that Rocked the Box Canyon

The pursuit for gold and silver in Colorado started well before whites came with dynamite, and even before Spanish colonizers. Indigenous miners didn’t have an official record of their well-established practices until the explorer Juan Rivera discovered ancient smelters near the Los Pinos River in 1765.

But it wasn’t until after the California Gold Rush in the 1850s, followed by the Civil War, that Colorado’s sierras would become a major enterprise. In 1872, a prospector named Linnard Remine trekked into the valley, and illegally built a cabin on the Utes’ land to pan for gold in the San Miguel River, per Valley Floor Preservation.

He was one of the many trespassers setting up shop in the area, like William Baker who was 12 miles over the mountains near Silverton. As flecks of silver and gold shimmered into their iron pans as they’d hoped, businessmen, and synonymously the United States, saw no other option than to force the Utes out completely.

The transaction came in the form of the Brunot Agreement in 1873, which stated that the Utes “agreed” to sell the majority of their stake in the San Juan Mountains. The unalloyed summits were now mere opportunities to those rugged enough to pursue them, pickaxe in hand, candle in hat.

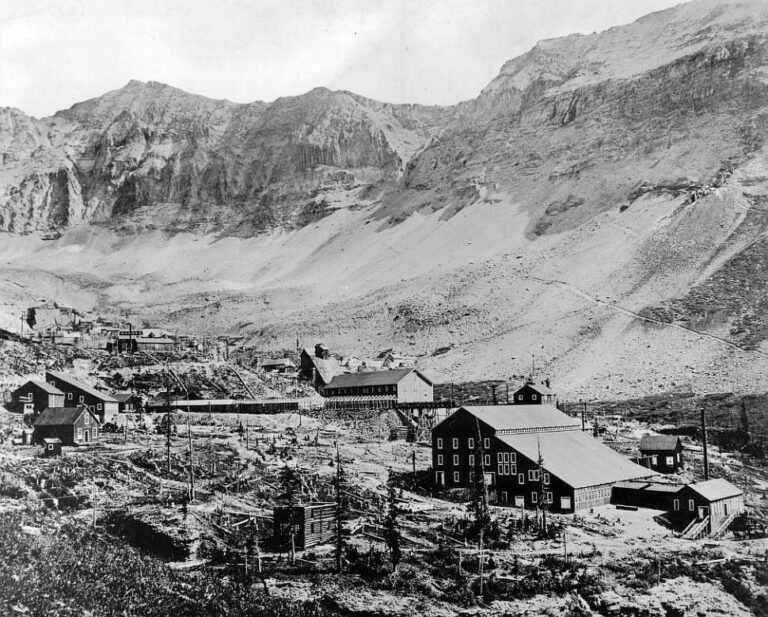

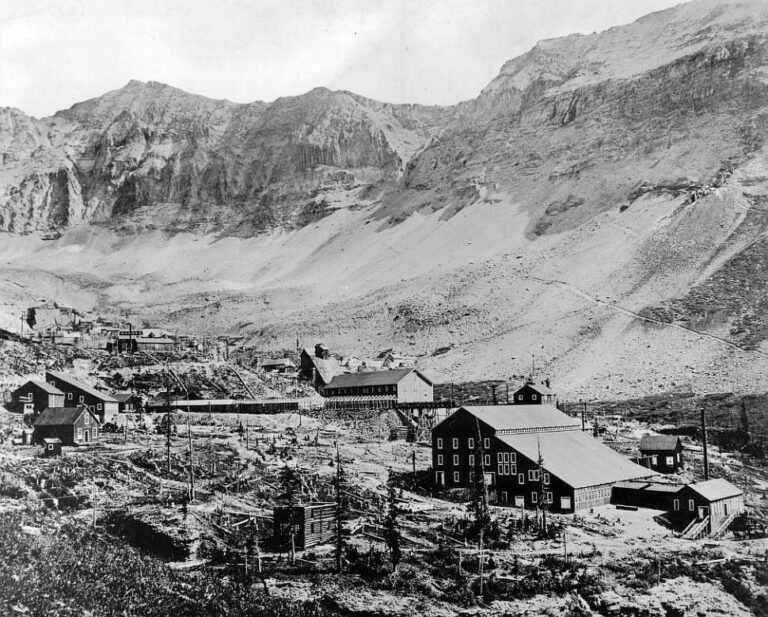

Among the hounds clambering into the San Juan Mountains was one named John Fallon, who had quite the nose for following veins. He struck big in Marshall Basin in 1875, and started the first official mines above Telluride; the Sheridan and Union.

Quickly after Fallon’s find, a group well aware that his claim extended past the legal allowance, the Smuggler Mine was claimed in the same basin, per Mining History Association. The surrounding slopes would flood with similar strikes thereafter.

Becoming Telluride

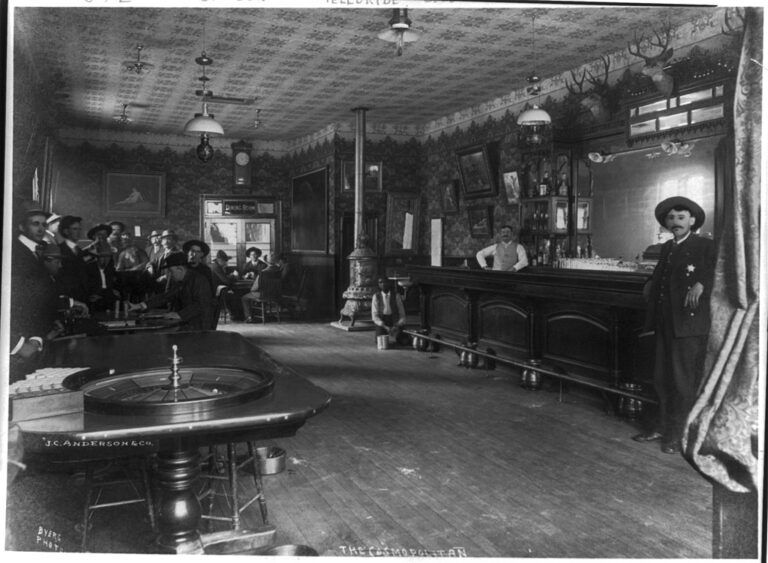

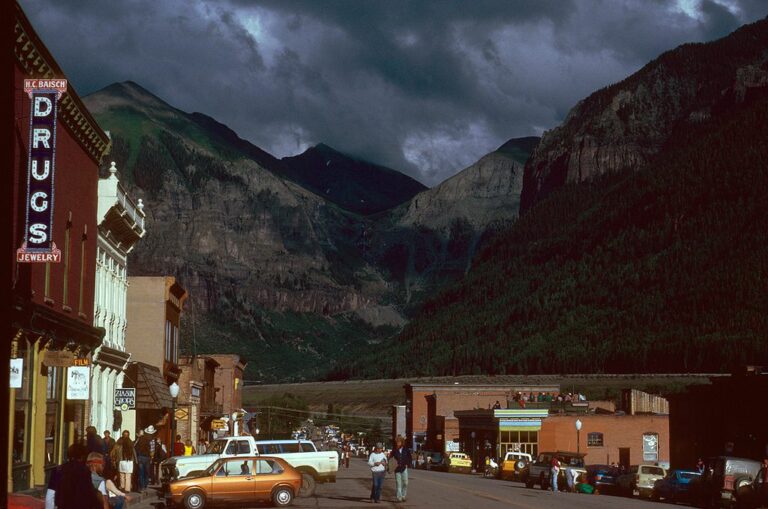

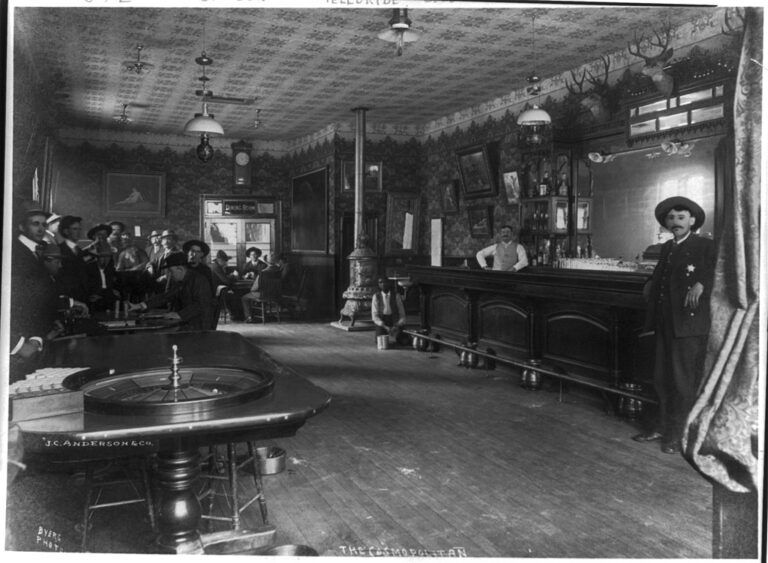

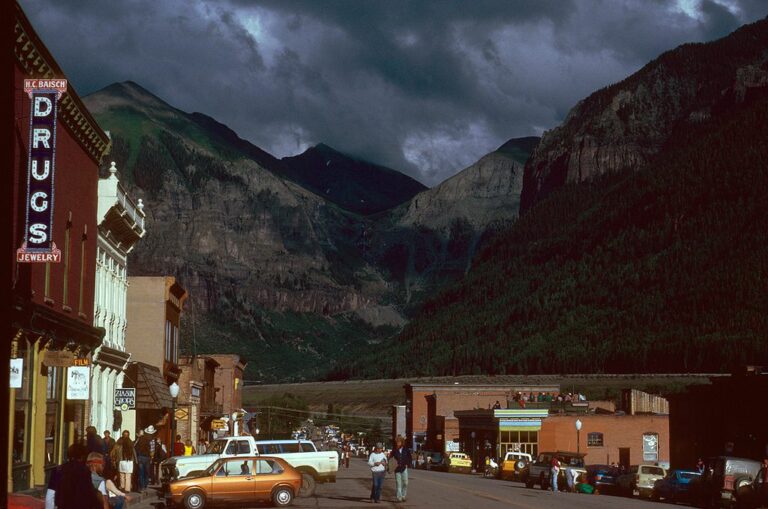

The box canyon quickly developed with hotels, bustling brothels, and unruly saloons to service the miners. As with all mining town culture at the time, shootouts, robberies, and any other debauchery was completely common here. The locals were typically unphased by it, if they weren’t already the instigators.

As an example of “other debauchery,” one of the house rules of the Sheridan Hotel requested that patrons not ride their horses up the stairs, per Telluride TV. It was also encouraged not to shoot the piano player.

Telluride also hosted the first bank robbery of the infamous outlaw Butch Cassidy in 1889. It was an easy heist from the San Miguel Bank, as the bunch simply waited until there was only one teller in the building, making out with $20,000, per True West Magazine.

The town was officially incorporated in 1878 under the name Columbia. But after 8 years of the postal service sending the wrong mail to Columbia, California on account of commonly hideous handwriting, it requested the Colorado camp to change its name.

The town was renamed after some misidentified ores that were thought to contain tellurium, aka tellurides, per Mining History Association. Tellurium doesn’t exist in the San Juan Mountains, but it made for a very fitting nickname; “To Hell You Ride” as locals often shot at the train as it chugged into town.

Telluride luckily had plenty of other gold. This allowed it to withstand the repeal Sherman Silver Purchase Act that put many of the nearby mining towns belly up. It alternatively stayed so profitable, the train carried a sign that said it was “Town without a Bellyache.”

Mining transitioned to lead, zinc and copper in 1941 to supply ammunition for World War II. These operations would slowly dwindle until 1978, leaving Telluride dirty, ultra polluted, and close to abandoned. But those who loved it stayed behind on wooden skis. Their eyes stayed steady on the steep, powder-puffed slopes above a boarded up Colorado Avenue.

A Birthplace of Modern Electricity

By 1890, Telluride and the basins above were barren from building the town and powering the mills. Coal needed to be shipped in to run the mining operations, which at that time was on the backs of mules. It was incredibly expensive, and companies were losing most of their revenue to move metal— be it out of town or out of the mountain, per Rocky Mountain PBS.

All mining in Telluride was on the brink of collapse. It probably would have met the end before the turn of the 20th century, if it hadn’t been for a local oddball with big dreams and an electrical inventor.

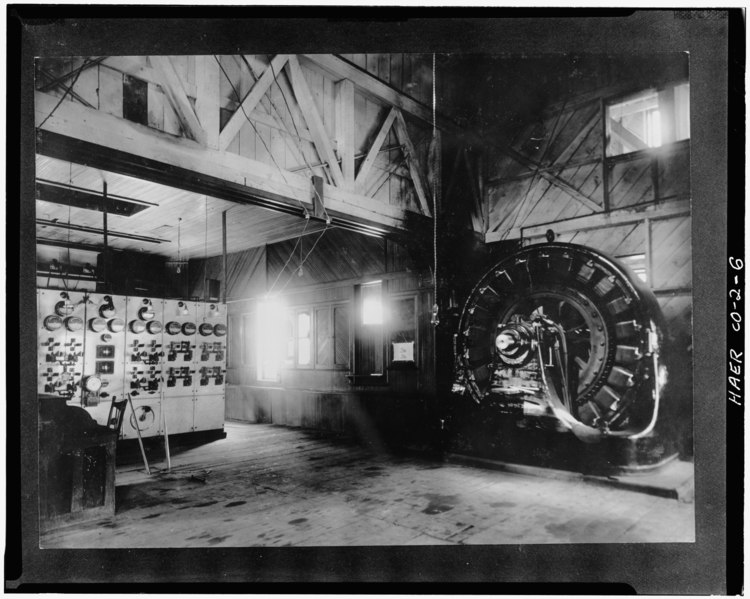

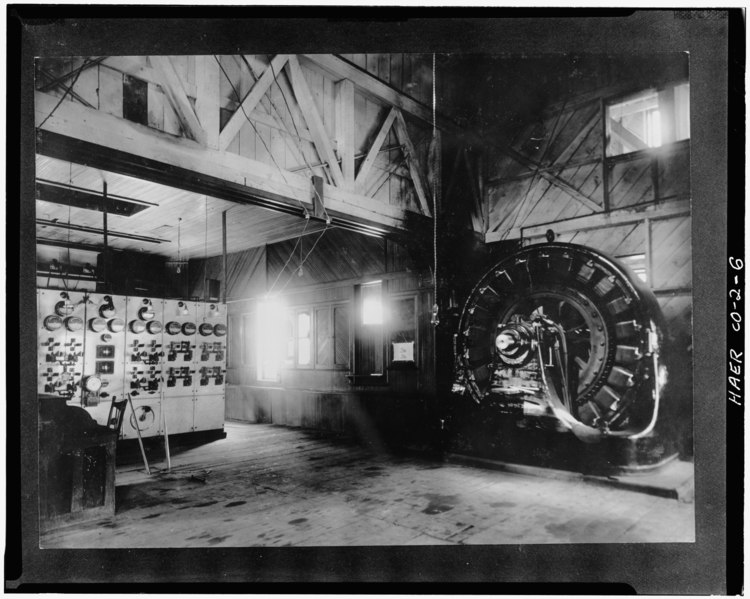

The oddball was L.L. Nunn, the inventor was George Westinghouse, who happened to be a colleague of Nikola Tesla. Both were interested in using Tesla’s controversial alternating current theory for a power plant, a feat that had never been done before, especially in a terrain so unkind and inconvenient.

Using the water from Trout Lake, and the gravity of the cliffs above the settlement of Ames, this cutting edge installation in the making had a promising future. Although many were not convinced it would turn on a single light bulb, let alone power drills and mills.

Nunn recruited electrical engineering students from across the country to help make it happen. Under Westinghouses’s supervision, they built everything, from the hydroelectric generator in a two room wooden shack, to the power lines three miles up to the Gold King Mine, all in a year’s time, per Rocky Mountain PBS.

This hydroelectric alternating current system was not only the first power source of its kind, it was the first to power an entire network. It ran to the Gold King Mine to the box canyon below, making Telluride the first town to run on electricity from a power plant. By 1894, all of the mines in the area were powered by Ames.

Once the word was out, the technology was immediately used at Niagara Falls, then across the United States and other countries thereafter. Xcel Energy now owns the Ames Power Plant, which continues to electrify Telluride.

Transforming into a High End Ski Haven

Telluride’s main attraction is its world renowned ski resort. It boasts the longest vertical drop in the country at a palm-sweating 4,425 feet. With 148 runs serviced by 19 lifts, in tow with some of the best snow in Colorado— not to mention a one-of-a-kind gondola, it’s easy to see why people flock to this granite corner of the San Juans.

Skiing has always been a pastime in Telluride. The runs were originally earned by a laborious trudge up the steep hillsides, until a school teacher put in a rope tow in the 1930s, per Telluride Ski and Golf Resort. It wasn’t until 1975 that the fun of skiing here was taken seriously.

It was Ron Allfred who took it seriously, despite not being much of a skier but a motivated real estate developer no doubt. After driving up to where Mountain Village stands today, to see the gradient ripple into a wall of Rocky Mountains, Alfred wholeheartedly believed that he had found America’s greatest ski resort.

The town was resistant to this enormous change for the first few years, holding onto the virtue that no one ventured these vistas anymore. But as the lifts started lining up the hill, the residents quickly warmed to the idea of being floated up their beloved runs.

In 1985, the construction of Mountain Village began along with the airport. Then came the custom gondola with the help of insight from the French. This essential addition was made possible by real estate funding, which in turn allowed it to be free to ride, per Telluride Ski and Golf Resort.

Mountain Village was officially incorporated in 1995. Since then, it’s become a hotspot for vacation homes for the rich and famous— including Tom Cruise and Oprah Winfrey, to name two of many. Today, around 1,500 people live in Mountain Village year round. During peak vacation times, the town hosts up to 20,000 with visitors.

Battles Between Man and the Environment

Driving into Telluride, it might come as a surprise that its magnificently blue sky, sparkling streams, and wide open spaces were only possible from constant conservation efforts since being taken from the Utes.

Mining quickly dilapidated the San Miguel River, which residents and other business owners never took lightly. In 1893, the Ames Power Plant sued the mines for contaminating the streams so much that the turbines couldn’t operate, per Sturm College of Law. By the early 20th century, the river was so filthy no one dared to fish, let alone drink from it.

Over the next few decades, courts increasingly began to recognize the importance of preservation needed in Colorado as the mining practices were completely unregulated. For decades they had been allowing acid and tailings to pour right into essential waterways and kill them completely.

Air pollution was also a major issue in Telluride given how its topography doesn’t naturally ventilate. In 1986, Telluride’s air quality was 17 times worse than the national air standard. It was well above Denver, one of the most notoriously polluted cities in the western United States.

After smothering the use of wood burning stoves and enforcing strict emission standards across San Miguel County, the area eventually became compliant with air standards in the early 2000s, per San Miguel County.

Another fight Telluride has had to maintain its natural beauty was for the valley floor. The conflict began in 1993 with the San Miguel County Corporation. Contrary to its name, it wasn’t owned by the local government, but by a military contractor tycoon, Neal Blue, per PBS.

Following the purchase of the riparian wilderness leading into the box canyon, Blue planned to replace it with a resort and golf course. The community was vehement, as it violated their local constitution to preserve the majority of the area as open space.

To save the valley from becoming an exclusive putting green, they would have to purchase it for 50 million dollars. It was a long shot—pun intended— but with a combination of private donations, bake sales, a wishing well, and other unconventional modes of fundraising, they made a miracle happen.

The valley floor was purchased and thus saved in 2008. Today, it remains untamed for the wildlife that depends on it and the people who truly appreciate it.

More Reading

How the Silver Boom Made Southwest Colorado and Its Wild Mining Towns

The Explosive Geology of the San Juan Mountains — A Past of Big Peaks

Telluride History — A Canyon of Constant Transformation

Telluride‘s past is much like its mountains. There was unbelievable beauty and balance, juxtaposed by the harsh bite of change, not unlike an unwelcome and commonly early winter. But as we all know change is inevitable in the alpine, especially when people get involved.

It is an understatement to say that this corner of Colorado has been To-Hell-You-Ride and back. From its status as an ancient haven for indigenous hunters, to becoming a status symbol in and of itself, Telluride‘s evolution has been as dramatic as the summits that surround it.

Between the flow of protecting its natural beauty and the ebb of enterprising it, read on to learn about Telluride‘s transformation.

Before it was Telluride

“The Utes believed that they didn’t own the land, but that the land owned them.” per Southern Ute Nation.

Before the mid 1800s, this box canyon— along with the rest of Colorado— was indelibly pristine. The only alterations it saw were the temporary hunting camps of the Nuuchu, renamed Ute by Spanish explorers.

For over 700 years, the Rocky Mountains and beyond were home to various bands of the Ute. The band that frequented the area was the Tabeguache (pronounced tab-uh-wash), although all 7 bands intermingled as they moved between the mountains.

This culture was (and still is) dedicated to balance with the environment, attuning to nature’s rhythm to not over harvest for game or plants. It kept their lifestyle semi-nomadic to allow for periods of replenishment, so they undulated between the cool alpine in spring and high deserts in winter.

Their existence and Creation Story was heavily influenced by the land, with many legends of the Coyote, Bear and Lion. And as master equestrians and traders since the 15th century, the Utes were a dynamic entity that avidly safeguarded this sacred landscape for centuries.

Despite the encroachment of white settlers, they were able to maintain mostly peaceful relationships into the 19th century. But in 1849, the paradigm of man owning land overpowered the Utes’ long way of life.

The nation was forced to sign a Treaty to recognize the United States as a sovereign nation, creating new imaginary boundaries of Ute land, per Southern Ute Nation. This treaty would be the first of many that would eventually push the Utes out the Rockies, and into the small reservations in Colorado and Utah we know today, per Colorado Encyclopedia.

The Boom that Rocked the Box Canyon

The pursuit for gold and silver in Colorado started well before whites came with dynamite, and even before Spanish colonizers. Indigenous miners didn’t have an official record of their well-established practices until the explorer Juan Rivera discovered ancient smelters near the Los Pinos River in 1765.

But it wasn’t until after the California Gold Rush in the 1850s, followed by the Civil War, that Colorado’s sierras would become a major enterprise. In 1872, a prospector named Linnard Remine trekked into the valley, and illegally built a cabin on the Utes’ land to pan for gold in the San Miguel River, per Valley Floor Preservation.

He was one of the many trespassers setting up shop in the area, like William Baker who was 12 miles over the mountains near Silverton. As flecks of silver and gold shimmered into their iron pans as they’d hoped, businessmen, and synonymously the United States, saw no other option than to force the Utes out completely.

The transaction came in the form of the Brunot Agreement in 1873, which stated that the Utes “agreed” to sell the majority of their stake in the San Juan Mountains. The unalloyed summits were now mere opportunities to those rugged enough to pursue them, pickaxe in hand, candle in hat.

Among the hounds clambering into the San Juan Mountains was one named John Fallon, who had quite the nose for following veins. He struck big in Marshall Basin in 1875, and started the first official mines above Telluride; the Sheridan and Union.

Quickly after Fallon’s find, a group well aware that his claim extended past the legal allowance, the Smuggler Mine was claimed in the same basin, per Mining History Association. The surrounding slopes would flood with similar strikes thereafter.

Becoming Telluride

The box canyon quickly developed with hotels, bustling brothels, and unruly saloons to service the miners. As with all mining town culture at the time, shootouts, robberies, and any other debauchery was completely common here. The locals were typically unphased by it, if they weren’t already the instigators.

As an example of “other debauchery,” one of the house rules of the Sheridan Hotel requested that patrons not ride their horses up the stairs, per Telluride TV. It was also encouraged not to shoot the piano player.

Telluride also hosted the first bank robbery of the infamous outlaw Butch Cassidy in 1889. It was an easy heist from the San Miguel Bank, as the bunch simply waited until there was only one teller in the building, making out with $20,000, per True West Magazine.

The town was officially incorporated in 1878 under the name Columbia. But after 8 years of the postal service sending the wrong mail to Columbia, California on account of commonly hideous handwriting, it requested the Colorado camp to change its name.

The town was renamed after some misidentified ores that were thought to contain tellurium, aka tellurides, per Mining History Association. Tellurium doesn’t exist in the San Juan Mountains, but it made for a very fitting nickname; “To Hell You Ride” as locals often shot at the train as it chugged into town.

Telluride luckily had plenty of other gold. This allowed it to withstand the repeal Sherman Silver Purchase Act that put many of the nearby mining towns belly up. It alternatively stayed so profitable, the train carried a sign that said it was “Town without a Bellyache.”

Mining transitioned to lead, zinc and copper in 1941 to supply ammunition for World War II. These operations would slowly dwindle until 1978, leaving Telluride dirty, ultra polluted, and close to abandoned. But those who loved it stayed behind on wooden skis. Their eyes stayed steady on the steep, powder-puffed slopes above a boarded up Colorado Avenue.

A Birthplace of Modern Electricity

By 1890, Telluride and the basins above were barren from building the town and powering the mills. Coal needed to be shipped in to run the mining operations, which at that time was on the backs of mules. It was incredibly expensive, and companies were losing most of their revenue to move metal— be it out of town or out of the mountain, per Rocky Mountain PBS.

All mining in Telluride was on the brink of collapse. It probably would have met the end before the turn of the 20th century, if it hadn’t been for a local oddball with big dreams and an electrical inventor.

The oddball was L.L. Nunn, the inventor was George Westinghouse, who happened to be a colleague of Nikola Tesla. Both were interested in using Tesla’s controversial alternating current theory for a power plant, a feat that had never been done before, especially in a terrain so unkind and inconvenient.

Using the water from Trout Lake, and the gravity of the cliffs above the settlement of Ames, this cutting edge installation in the making had a promising future. Although many were not convinced it would turn on a single light bulb, let alone power drills and mills.

Nunn recruited electrical engineering students from across the country to help make it happen. Under Westinghouses’s supervision, they built everything, from the hydroelectric generator in a two room wooden shack, to the power lines three miles up to the Gold King Mine, all in a year’s time, per Rocky Mountain PBS..

This hydroelectric alternating current system was not only the first power source of its kind, it was the first to power an entire network. It ran to the Gold King Mine to the box canyon below, making Telluride the first town to run on electricity from a power plant. By 1894, all of the mines in the area were powered by Ames.

Once the word was out, the technology was immediately used at Niagara Falls, then across the United States and other countries thereafter. Xcel Energy now owns the Ames Power Plant, which continues to electrify Telluride.

Transforming into a High End Ski Haven

Telluride’s main attraction is its world renowned ski resort. It boasts the longest vertical drop in the country at a palm-sweating 4,425 feet. With 148 runs serviced by 19 lifts, in tow with some of the best snow in Colorado— not to mention a one-of-a-kind gondola, it’s easy to see why people flock to this granite corner of the San Juans.

Skiing has always been a pastime in Telluride. The runs were originally earned by a laborious trudge up the steep hillsides, until a school teacher put in a rope tow in the 1930s, per Telluride Ski and Golf Resort. It wasn’t until 1975 that the fun of skiing here was taken seriously.

It was Ron Allfred who took it seriously, despite not being much of a skier but a motivated real estate developer no doubt. After driving up to where Mountain Village stands today, to see the gradient ripple into a wall of Rocky Mountains, Alfred wholeheartedly believed that he had found America’s greatest ski resort.

The town was resistant to this enormous change for the first few years, holding onto the virtue that no one ventured these vistas anymore. But as the lifts started lining up the hill, the residents quickly warmed to the idea of being floated up their beloved runs.

In 1985, the construction of Mountain Village began along with the airport. Then came the custom gondola with the help of insight from the French. This essential addition was made possible by real estate funding, which in turn allowed it to be free to ride, per Telluride Ski and Golf Resort.

Mountain Village was officially incorporated in 1995. Since then, it’s become a hotspot for vacation homes for the rich and famous— including Tom Cruise and Oprah Winfrey, to name two of many. Today, around 1,500 people live in Mountain Village year round. During peak vacation times, the town hosts up to 20,000 with visitors.

Battles Between Man and the Environment

Driving into Telluride, it might come as a surprise that its magnificently blue sky, sparkling streams, and wide open spaces were only possible from constant conservation efforts since being taken from the Utes.

Mining quickly dilapidated the San Miguel River, which residents and other business owners never took lightly. In 1893, the Ames Power Plant sued the mines for contaminating the streams so much that the turbines couldn’t operate, per Sturm College of Law. By the early 20th century, the river was so filthy no one dared to fish, let alone drink from it.

Over the next few decades, courts increasingly began to recognize the importance of preservation needed in Colorado as the mining practices were completely unregulated. For decades they had been allowing acid and tailings to pour right into essential waterways and kill them completely.

Air pollution was also a major issue in Telluride given how its topography doesn’t naturally ventilate. In 1986, Telluride’s air quality was 17 times worse than the national air standard. It was well above Denver, one of the most notoriously polluted cities in the western United States.

After smothering the use of wood burning stoves and enforcing strict emission standards across San Miguel County, the area eventually became compliant with air standards in the early 2000s, per San Miguel County.

Another fight Telluride has had to maintain its natural beauty was for the valley floor. The conflict began in 1993 with the San Miguel County Corporation. Contrary to its name, it wasn’t owned by the local government, but by a military contractor tycoon, Neal Blue, per PBS.

Following the purchase of the riparian wilderness leading into the box canyon, Blue planned to replace it with a resort and golf course. The community was vehement, as it violated their local constitution to preserve the majority of the area as open space.

To save the valley from becoming an exclusive putting green, they would have to purchase it for 50 million dollars. It was a long shot—pun intended— but with a combination of private donations, bake sales, a wishing well, and other unconventional modes of fundraising, they made a miracle happen.

The valley floor was purchased and thus saved in 2008. Today, it remains untamed for the wildlife that depends on it and the people who truly appreciate it.

More Reading

How the Silver Boom Made Southwest Colorado and Its Wild Mining Towns

The Explosive Geology of the San Juan Mountains — A Past of Big Peaks