The majority of the information in this article about the naming (and renaming) of Southwest Colorado rivers on the Juan Rivera expedition, including Rivera’s journal excerpts, has been sourced from the incredible and comprehensive work of Steven G. Baker and Rick Hendrick’s Juan Rivera’s Colorado, 1765.

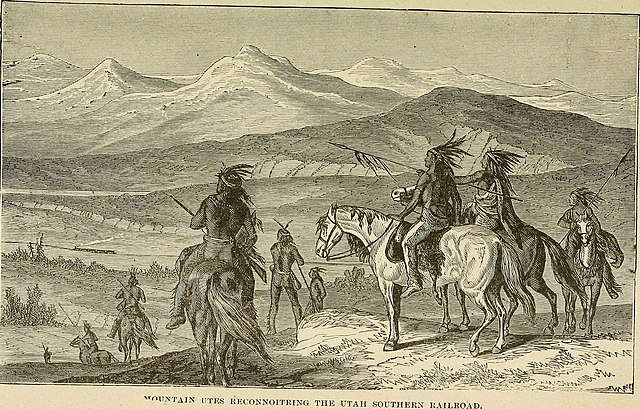

In the mid 1700s, the rugged region we know today as Southwest Colorado was hanging onto its last years in the rightful possession of the Ute nations, yet to be colonized. That era wouldn’t come until nearly a century later, when the “Colorado Silver Boom” would reverberate through the San Juan Mountains following the Civil War.

Occasional traders were the only white newcomers to visit the borders of the area, and they never stayed long as it was quite clear they were quite unwelcome. The reputation here was dangerous enough for the Royal Order to prohibit travel beyond New Spain’s borders.

But since New Spain ruled the territory of today’s New Mexico, and other Europeans from the East were starting to mosey West, the Spanish were pressed to understand what waited in those rugged peaks up north.

Their only knowledge of the Rockies and beyond came from the local Pueblo people and Utes who visited New Mexico. They spoke of light-skinned natives with long beards in the legend-filled land of Teguayo. And of silver laden mountains, and a crossing of the massive Rio del Tizon— now called the Colorado River.

The Spanish wanted to know if any of this was true— And more importantly, if the residents of these unexplored lands were amicable with Europeans. All of this information would be used for potential colonization efforts, and subsequently military endeavors.

Introducing, Juan Antonio Maria de Rivera

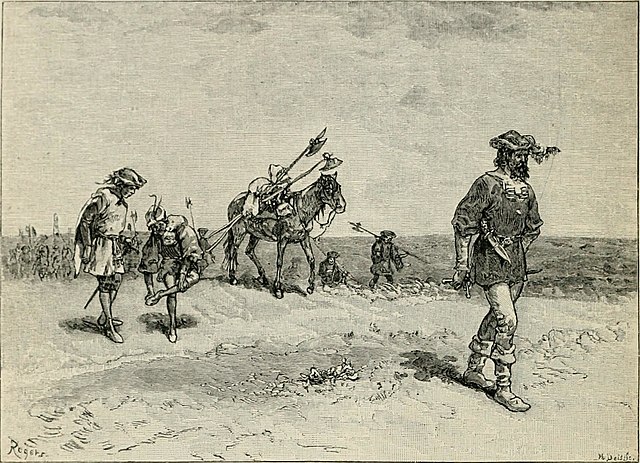

So in the spring of 1765, New Mexico’s Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín appointed a middle class, 27-year-old to lead the very first organized expedition into Southwest Colorado. His main objectives were; To map the trails, learn about the indigenous people of the region, find a crossing of the mighty Colorado River, and if time allowed– prospect for silver.

Hardly anything is known about the explorer of this maiden voyage, let alone why he was put in such an exclusive position to carry it out. What we do know is that he was Juan Antonio Maria de Rivera.

We also know that his detailed journals from the expedition left a legacy, and were vital for further Spanish exploration of the West— Particularly of the widely known Dominguez Escalante Expedition in 1776.

Here is a summary and excerpts from Rivera’s journals (translated into English), following his enterprising journey into the Ute territory of today’s Southwest Colorado.

The Expedition Begins: June 25, 1765

From dusted mesas crumbling into a vast and unkind alpine, looming in an elusive corner of the Colorado Plateau, the expedition set out for what was dangerously undiscovered. Rivera, a few fellow Spaniards, a band of stout mules and brave horses, and most importantly— a native interpreter, began their journey from Abiquiu, New Mexico.

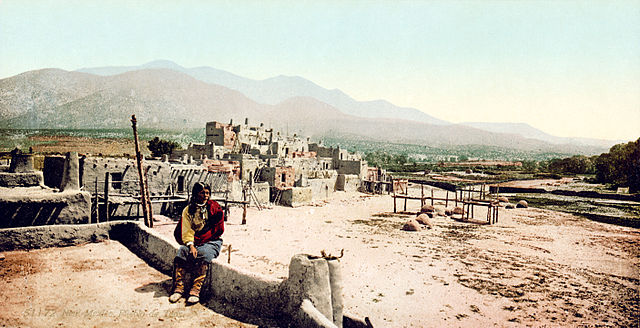

Abiquiu was the northernmost meeting point in New Mexico for tribes and Spanish to trade. The markets here were commonplace, and supplied anything and everything from both cultures, from swords to turquoise, from horses to pumpkin seeds, from Paiute slaves to elk jerky. However, the Utes were uninhibited to come further down to Santa Fe or Taos for their business if needed.

They followed the ancient trail headed northwest, one that was first made by animals and widened by humans over thousands of years. They would spend four days undulating between hills and canyons, before reaching the first rivers of the expedition.

It’s often thought that Rivera named all of these rivers himself, but they of course already had titles and the expedition’s interpreter, Joaquin, knew most of them. So Rivera would just translate the Ute names into Spanish names, with the exception of a few.

Members of the Expedition:

Juan Rivera Antonio Maria de Rivera

Joaquin Trujillo: The interpreter, a Genizaro (mixed Kiowa and Spanish heritage) from the Pueblo of Abiquiu

Antonio Martin

Gregorio Sandoval

Adres Sandoval

Jose Martin

Miguel Abeita

Andres Chama

June 30, 1765: The Navajo and San Juan Rivers

They crossed the Rio Navajo, a previously named stream. This title most likely came from the Tewa people, who called the Dine tribe a word pronounced “nava hu,” meaning cultivated fields.

After a few short miles, they came upon “a much larger river than the one mentioned, which is very delightful and pleasant, that we named San Juan. It has many meadows and a lot of pasturage.” Rivera wrote.

July 1, 1765: Crossing the Piedra River

The group continued northwest, trudging through one swampy canyon after another. After an obligatory siesta for the men and animals, followed by more trekking…

“We arrived at the river the Utes call the [Rio] de la Piedra Parade where we slept.”

Translated from both languages, this was Stone River. Those who have traveled within the Piedra River’s granite box canyons will find the name astute. In summer, the Piedra is quaint. In spring, it is tumultuous depending on where you cross it.

The group found the stream around 15 miles from today’s Pagosa Springs. The sacred spring of Pagosa (meaning healing or boiling water in Ute), is the deepest geothermal pool on Earth, and wouldn’t be discovered, or at least recorded, by colonizers for another century.

The following day, the group would stop in the afternoon at an empty Ute hunting hut, which mostly likely resembled a sort of wikiup. These structures were dome shaped, constructed with slender tree branches as the frame, and covered with brush or smaller branches. They were widely used by tribes spread across Colorado and Utah.

Due to the midday heat, along with the impressive ascent of the upcoming ridge, Joaquin suggested that they continued the following morning to save the horses and mules from exhaustion. As a group who greatly appreciated their steads, they agreed.

July 3, 1765: The Pinos River and Ancient Mining Remnants

“Having finished descending that slope we entered a canyon of soft earth without rocks that is three leagues long and comes at a large river the Utes call the [Rio] de los Pinos. It has many meadows, good pasturage, and its waters came to the shoulder blades of the horses.”

If not already apparent by the name, this river has many, many pine trees!

“Examining it because of its beautiful locations, we began to see along its banks the ruins of old buildings that provided evidence of having been a pueblo. There are still many burnt adobes as though from the bottom of a smelter. Carrying out the necessary investigations with greater reflection and care, we found among the ruins of the pueblo something like a smelter in which they smelt ore, which appeared to be gold. We gathered some burnt adobes from it to show them to the governor.”

July 4, 1765: Crossing the Florida and Arriving at the Animas River

Continuing west, the group comes across a river the Utes called the “Rio Florido,” today’s Florida River (pronounced flo-ree-duh). Florido in Spanish means flowery.

During their siesta, Rivera noted:

“We saw the same signs as at the [Rio] de los Pinos of ruins of pueblos, burnt ore, adobes, and so forth. After examining everything, we departed from that campsite… until we arrived at a river so copious and large that it exceeded the Rio del Norte, which we named the Rio de las Ànimas.”

Translated, Rivera had named these tumultuous waters “The River of Souls.” Today, it’s been shortened to the Animas River.

As for his comparison, the Rio del Norte is understood to be the upper Rio Grande River. Rivera would have been very familiar with this section of river in New Mexico, mostly likely through Taos and perhaps farther north.

They spotted a Ute camp across the river (which they called rancherias) of the great captain El Coraque. They would have to camp along the banks that evening, as crossing this section of the Animas River would need more planning, and guts.

July 5, 1765: Crossing the Animas River

“We spend the whole day crossing the river because of the large amount of water and the gradient, for the water came up on the horses above the hind bow of the saddle.”

Once across, they joined the Utes who customarily served them dinner and tobacco. They asked Coraque for the guide who had arranged to help them search for silver in the area. His name was Cuero de Lobo, aka Wolf Skin.

Luckily the tribe knew of him, but he had “gone to the land of the Payuchis to visit his mother-in-law.” They told Rivera there was a woman downstream who could tell him where to find the silver he seeked.

July 6, 1765: A Face Like the Devil

The crew headed south as instructed by Coraque, where they met the woman who supposedly had the information they wanted.

“We began to ask questions at which point the Ute women made such a ferocious face that between her and the Devil there was no difference.”

After the camp’s captain questioned the woman about her manners, she relented and gave them the following directions:

They would find it up a “dry arroyo along the upper part that faces north… he should climb up, and he would see a Navajo house and a plot that is not small…” Nearby would be a flat plot of land. Here the silver would come up easily out of the ground, and they wouldn’t have to dig much to find it.

Rivera had heard of plots like this. He himself saw a Ute bring enough silver to a Blacksmith in Abiquiu to make a crucifix and two rosaries. And after the two ancient smelters they’d come across, he was hopeful.

July 8, 1765: A Long Walk for a Tall Tale

After traveling two days south to hopefully intercept Wolf Skin, the crew also followed the clues for the silver hill. While the terrain was just as the Ute woman described, and they did indeed find the Navajo house, their long and extensive search for shiny metal came up short.

It also didn’t help that the captain who encouraged her to share her secrets ended up joining them for this survey.

“…the great captain showed dislike and anger toward the Ute woman, strongly urging us to return where she was because he wanted to kill her for being a liar. It was a lot of work for us to restrain him, and tricking him with the little deceit that we would return to his rancheria, we calmed him down.”

They returned to their camp along a stream they called the Rio de Lucero (today’s Mancos River), and made further plans to find Wolf Skin.

July 14, 1765: Parting at the Dolores to Find Payuchis

The day prior, the party had split up at a river Rivera named Río de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores. Like the San Juan (named after Saint John the Baptist), Rivera seemed to default to Catholic figures when titling rivers. Señora de los Dolores— Our Lady of Sorrows — is the Virgin Mary after she has suffered many moments of grief.

While Rivera stayed at camp, a few men headed further north in hopes to find Wolf Skin. By a stroke of luck as they headed West, they came across Payuchi village across a large creek.

A Payuchi member jumped into the water to meet another party member halfway. They obliged. In the middle of the stream, the two spoke in signs and established that both sides didn’t want any trouble.

The Payuchis were interested to meet the rest of the expedition. So the next day, the crew took members of the tribe back to the Dolores where Rivera was waiting.

When they arrived on July 16, the tribe leader, Captain Chine, asked Rivera,

“…What were Spainards doing in such bad lands? What were they searching for?”

After Rivera told him they were looking for Wolf Skin, as well as the Rio del Tizon, Chine said,

“…it was true that Wolf Skin had been with them, but he had already returned to his land, and the Spaniards should not be stupid because that river was very far away and in bad land without pasturage or water. There are many sand dunes that would tire our horses, and the sun that shines on this route would burn us, for it is very strong and insufferable. Not knowing the route, we would suffer much hardship or we would die of hunger, and if not, one of the many nations there are before we arrived at that river would kill us. We should return to our land.”

July 17, 1765: Finding Wolf Skin and La Plata Mountains

After being rightfully discouraged from making the foolhardy journey through the unkind deserts to the Colorado River, Rivera and the group decided to turn back and look for Wolf Skin some more.

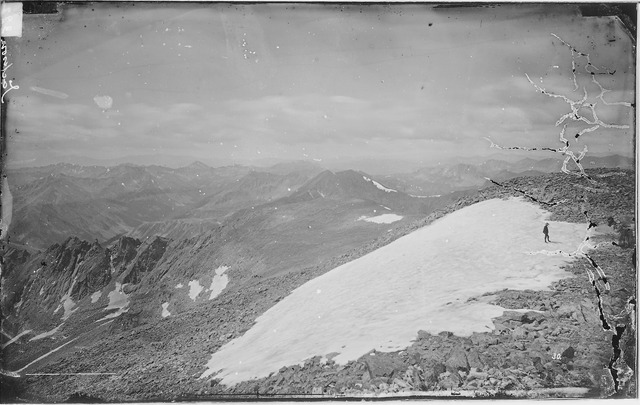

After traveling all day and part of the night, they arrived at the base of what Rivera named the La Plata Mountains. The Utes called the range Grulla.

It’s not clear if Rivera was phonetically spelling a Ute word or translating it to Spanish. If it was the latter, grulla means crane. The summits do soar up to 13,000 feet, after all. But Rivera seemed so hopeful to find silver in these mountains, it seems he couldn’t help but name them in light of those aspirations.

He also named the beautiful glittering stream here after the expedition’s beloved interpreter, San Joaquin. Today, it is simply the La Plata River.

“There we found about 20 Ute lodges and Cuero de Lobo. Giving gifts as best we could because we were out of supplies, the parley was arranged. He said that a horse should be readied for him for the next day, and we would go see the silver. We spent the rest of this day in conversations with the Utes about the aforesaid information, without acquiring anything new at all.”

July 19, 1765: More Searching for Silver

“It can be said without exaggeration that the whole sierra is pure ore and there is much to see.” Rivera wrote after two days spent on the crumbling slopes of these picturesque Rocky Mountains.

“Having examined what could be seen of that sierra, we found a hill that we called El Timichi. On the whole summit we saw a pueblo so large that it exceeds the population of Santa Cruz de la Canada in which there are many burnt ores and the same signs as in the previous pueblos. On the route one sees the vestiges of some old torreones that still preserve some pieces of the wall.”

July 23, 1765: Back to Santa Fe

With plans to return when the aspen leaves began to fall as the Payuchis instructed, with the promise that they would help Rivera find the crossing of the Colorado River, the expedition headed back for the week-long, painstakingly-scenic journey to Santa Fe.

There he would share his findings with Governor Cachupín, who was pleased enough with Rivera’s first go around (and miraculous survival), that he agreed to have him organize another expedition in the fall.

That expedition from October to November would prove to be far more precarious, as Rivera would meet less friendly indigenous people who were avid protectors of their land. He was, after all, exploring the landscape to eventually take it from them. But that story is for another time.

More Reading

How the Colorado Silver Boom Made Southwest Colorado and Its Wild Mining Towns