Before the mid 1800s, Colorado mining towns were nonexistent. The untapped land was home the original people known as the Ute, who migrated with the hunting season across this wild western territory. White settlers had made their way through these rugged mountains on the way to kinder terrain, but few had good reasons to establish settlements until 1859, via Rocky Mountain PBS.

When the California Gold Rush was in full pickaxe-swing in 1849, prospectors certainly couldn’t ignore these massive snowcaps on their way to the West Coast. So after Cali’s rush faded, its metal heads quickly set their sights on the Rockies. In 1861, due to the insistence of the gold diggers, the mineral-rich area joined the territories as Colorado— meaning, “colored red” in Spanish.

Southwest Colorado in particular had its own unique influx of character in the developing West. Its remote wildernesses made the journeys far more interesting (dangerous) along with the prominent presence of the area’s indigenous peoples.

Prospectors did begin finding some golden treasure in Southwest Colorado during this time, not on the scale of Idaho Spring or Breckinridge, but enough to keep them interested in the area per Uncover Colorado. But the Civil War would call for the burliest of brutes available, and it naturally left miners preoccupied with muskets and cannons rather than shovels and dynamite until 1865.

The Silver Boom

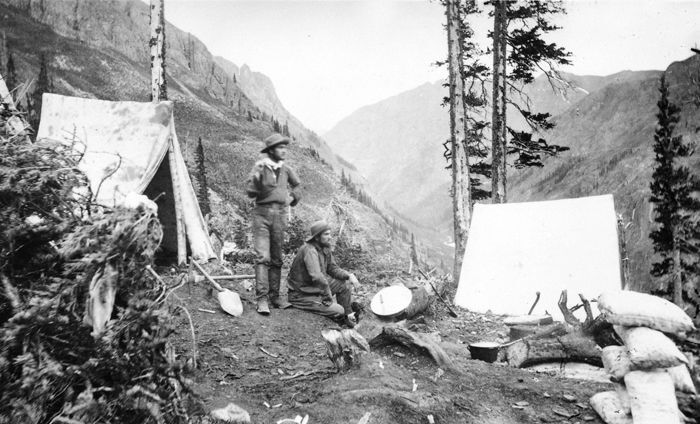

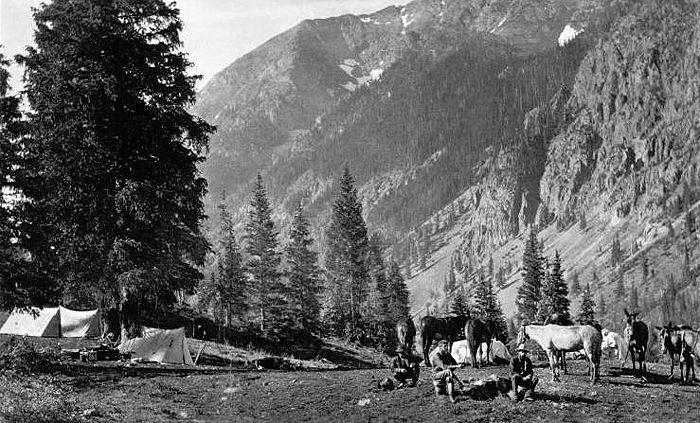

After the war, miners slowly started coming back to Colorado to get rich quick and head back to wherever they came from, be it New England or Russia, per Western Mining History. They arrived across the San Juan Mountains in fleets of wooden wagons on roads in the making, bumbling across country that the Utes knew to only visit during the game season.

And because these mountains had belonged to Utes for the past 500 years, tribes made it undoubtedly difficult for the heavily mustached newcomers blasting their sacred hunting grounds apart.

In an effort to “compromise” the rights to these prosperous lands, the Treaty of 1868 was signed by both tribe leaders and government officials. The document designated 18 million square miles of turf throughout Colorado and Utah to indigenous tribes, leaving them with a third of ownership over the Colorado territory— including the silver-loaded San Juan Mountains.

So when prospectors began striking away at veins anyway in indigenous lands, a makeshift deal known as the Brunot Agreement promptly came along in 1873, which sold off the San Juans from the Ute reservation.

Then in 1878, the price of silver shot up into the heavens due to the Bland-Allison Act. The law was instituted as a remedy to the five year depression, and hoisting the value of American currency by backing it with silver and gold. Congress was then required to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver from western mines every month.

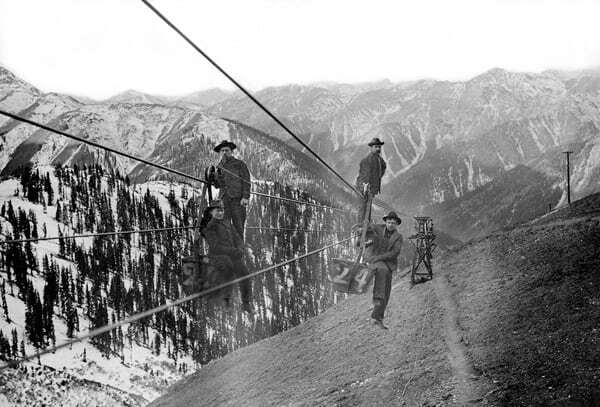

And so the wild, metal-laden peaks became fully open for big business. The area was staggeringly remote and undeveloped, and hauling freight to and from sources became the kickstarter of multiple technological ingenuities.

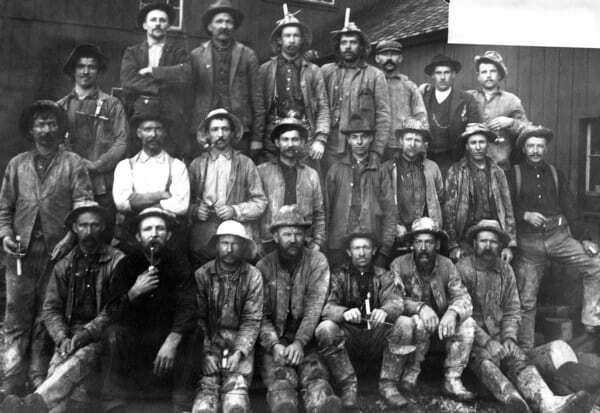

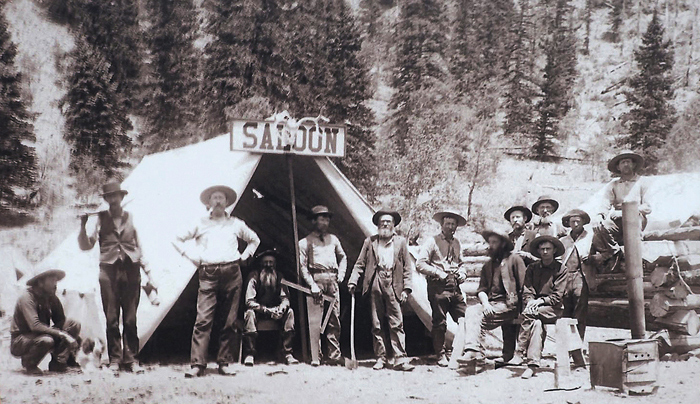

Meanwhile the mines were tunnels of treachery themselves, with shafts being easy to fall into, collapse, trap toxic gases, or flood. Miners who survived chipped away at the igneous for 10 hours a day in absolute darkness, with only candles in their hats to see what wall was their target. And when they rose from the depths, a town made of trigger-happy saloons and tragedy-stricken brothels were their only refuge.

Here is a nugget of history on the mining towns of Southwest Colorado that made the West so wild.

Silverton – Silver by the Ton

The glacially sculpted valley where Silverton rests was first known to white folks as Baker’s Park through the 1860’s. The namesake belonged to a Colorado gold rusher, Charles Baker, who found a respectable amount of gold fluttering through the contributing streams of the Animas River.

After the war and the miners returned, the booty was found farther north in Eureka, but the boys made their winter camp in a slightly lower altitude where the park was claimed. After the Brunot Agreement was finalized, settlers established this valley as “silver by the ton” in 1874, with other towns in the San Juan Mountains soon to follow, per the Durango Silverton Narrow Gauge.

Silverton and its northern mining settlements had a slow start the first few years; its only entry and exit was either up and over a 12,500 ft. high opening in the San Juans known as Stony Pass, or along a wiley toll road through Animas River Canyon. Such rugged treks lasted until July 8, 1882, when the tracks of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway emerged from the south. With cars immediately ready for passengers and ore, Silverton quickly grew to a population of 2,000 people.

Until the train became a major contributor to Silverton’s economy, it was as rough as any town of the Wild West. Playing hard after a long day in the mine could mean anything from a romp in the bawdy houses, lynchings, to shootouts after a bad hand of cards.

But as men began to bring their wives and children into Silverton, the town became divided at Greene Street— churches and schools on one side and brothels and saloons on the other, according to the Silverton Chamber of Commerce. If the madams were caught on the wrong side of the street, they were fined. But the punishments never came too harsh, as those fines helped pay to keep the town growing!

The boom lasted until the 1910’s, and the town quickly turned to tourism by 1913. But the search for precious metals continued on, just at a smaller scale at the Sunnyside Mine until 1991. Silverton also boasts the oldest running newspaper on the Western Slope; The Silverton Standard & the Miner.

Durango – The Town that Kept on Chuggin’

While Durango had a smidge of gold to be panned in the Animas River, it was really founded in 1881 for the purpose of smelting the ore that would come chugging out of Silverton within 8 months, per Rocky Mountain PBS. Its kinder topography where snow capped peaks rise in the backdrop rather than the front doorstep also made it more advantageous to move metal to the outside world.

General Palmer, the founder of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, named it Durango because it was reminiscent of Durango, Mexico, per Britannica. Zero points for originality, 10 for laying out the most successful Southwest Colorado town today.

In tow with Durango’s easier access to newcomers, the limestone quarry, coal mines and railroad made Durango grow with impeccable speed. Before the line to Silverton was even complete, over a hundred businesses popped up through the valley, 20 of them being brothels and saloons, per Durango.org.

The ladies who essentially ran the town were referred to as soiled doves, and like Silverton, were encouraged to walk on one side of Main Avenue to avoid any confusion with the not-for-profit women.

Like any other mining town in Colorado at the time, Durango was genuinely as rough as Wild West lore leads on. Since Durango grew much faster than law enforcement could be properly put in place, shootouts and hangings in the name of vigilante justice were respectively rampant in its salad days.

A notable character of the town’s wild beginnings was the Stockton Gang, a cow stealin’ band of vagabonds who had the audacity to open a butcher shop north of Durango.

One day in April of 1881, the New Mexican ranchers from whom the boys had been getting their steaks trotted into town for a cut of their own vigilante justice. The shootout ensued right on 2nd Avenue, and while no one was killed, and the townsfolk decided they’d had enough of flying bullets— at least from the Stocktons. The guys didn’t travel far though, as they simply settled up the tracks in Silverton to raise some more hell.

Unlike the other mining towns that immediately floundered when the price of Silver plummeted due to the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, Durango continued to flourish despite the ongoing gunfights and empty train loads.

With the construction of the Henry Strater Hotel in 1887 and Mesa Verde’s establishment as a National Park in 1906, Durango was able to survive the mining hardships better than the surrounding towns into the 20th century.

Ouray – For the Birds

Ouray (pronounced Your-Ray, and translates to “The Arrow” in Ute) had very similar beginnings to Silverton. Prospectors crested its peaks in 1861, and after the Brunot Agreement in 1973, miners came pouring into the box canyon that once served as the Utes sacred hunting grounds.

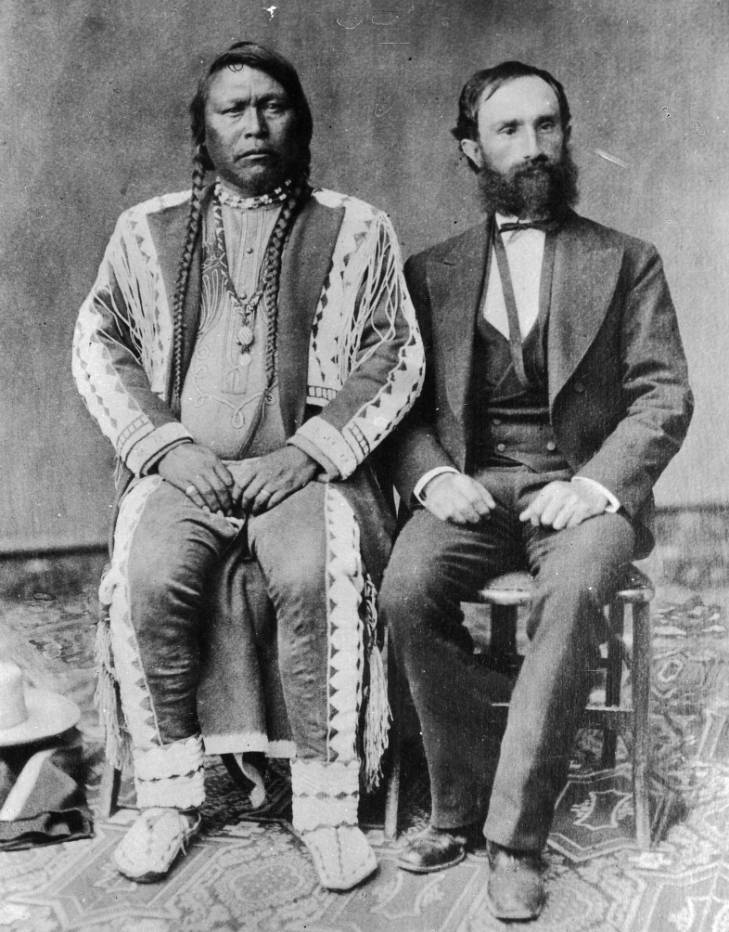

The town was named after the Ute Chief, Ouray, who essentially spoke for all southwestern native tribes over reservation negotiations with the Federal Government.

A story goes that in 1872 when Chief Ouray was first propositioned to sell more than half of the Utes’ Colorado lands, he quickly declined in respect to the Treaty of 1868. But the Chief confided in Felix B. Brunot, a Chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners, sharing the tragic story of his lost son. Ouray’s son, Pahlone, was captured and traded between the Lakota and Arapaho tribes in 1862, according to Colorado Encyclopedia.

Brunot sought out Ouray’s kidnapped heir and somehow, actually found him! When he was returned to his father, the Chief granted his approval to the Brunot Agreement and consequently changed Southwest Colorado forever. The mining area became the second top producer in the state, just behind Leadville located in central Colorado.

But the town of Ouray in particular grew slower despite the large production of silver. This was on account of the Denver & Rio Grande railway taking a hot minute to reach Ouray in 1887. The death-defying feat of laying the tracks over Red Mountain Pass was a huge credit to Otto Mears, aka the Pathfinder of the San Juans.

Otto was the fearless (and well-financed) fellow who established all of the majors routes of the San Juan Mountains, and who we can all thank today for the ability to ride a narrow gauge into Silverton and cruise the Million Dollar Highway.

And although the Silver Panic swept through Ouray in 1893 like its neighboring mining hubs, the Gold Belt discovery allowed its mines to continue making coin— especially the Revenue and Camp Bird, per Legends of America. The valley also steams with spectacular hot springs, so, that helped, a lot.

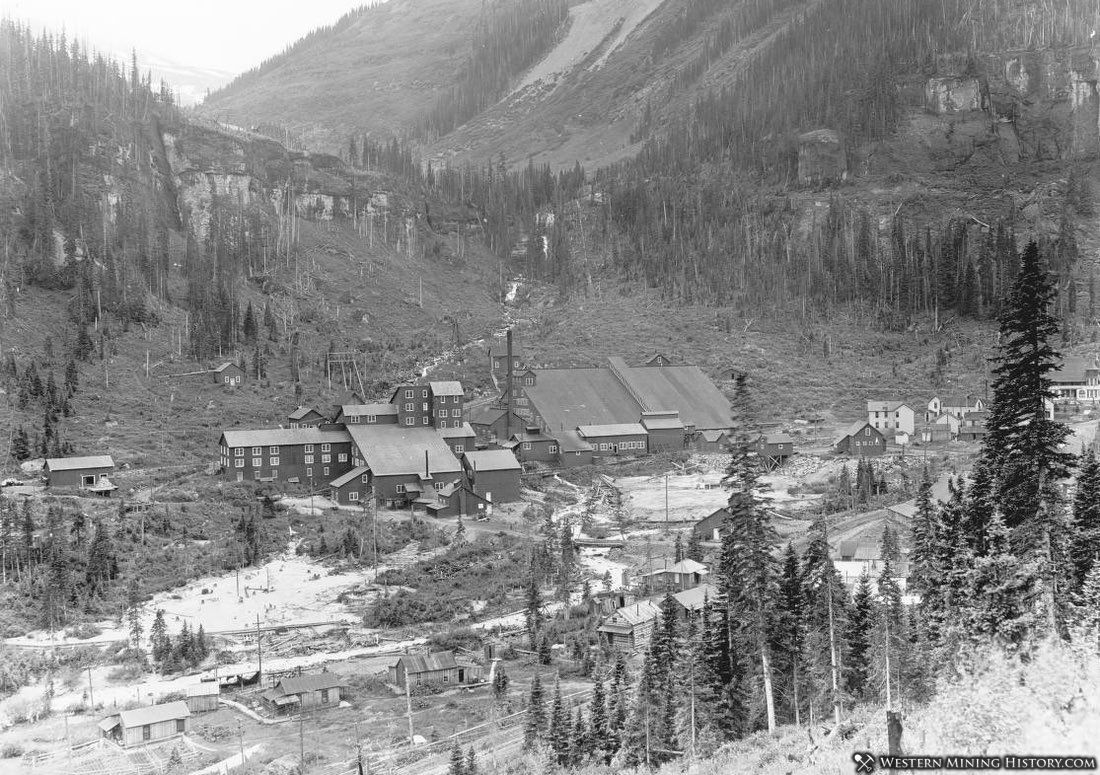

Camp Bird was so renowned for being one of Colorado’s richest mines, it actually became a tourist destination. The man who founded the mine, Thomas Walsh, was the most successful prospectors in Colorado after striking it big in Imogen Basin in 1896.

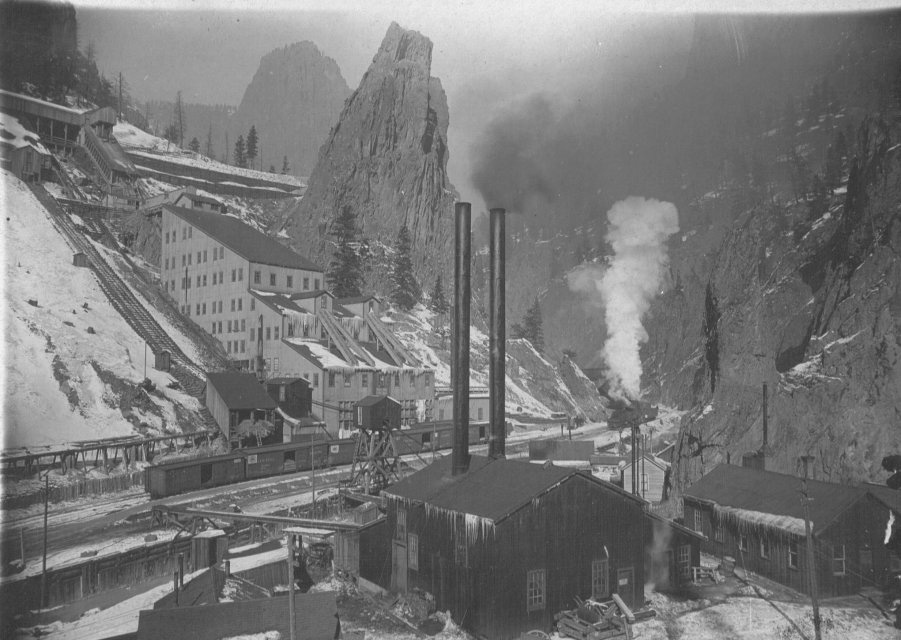

Within two years, the mine had an aerial tram for hauling materials down the mountain pass; a large, top of the line boarding house— electricity, porcelain tubs and warm water to oblige; a post office, and 200 miners, per Western Mining History.

Camp Bird was so hot that one day, a couple of bandits attempted to rob a stagecoach coming down from the mine. However they were unsuccessful in finding their loot, even though it was in a box beneath the driver’s seat. So, the two ignoramuses rode off into the mountains, empty handed on account of their own lack of diligence to find $12,000 dollars worth of gold ready for the taking.

Telluride – “To Hell You Ride”

The bougie ski town we know as Telluride today actually had one of the most humble beginnings of the mining boom in the San Juan Mountains. The mining camp was originally named Columbia in 1878, but the US Postal Service requested the name be changed on account of its easy confusion with Columbia, California.

According to Rocky Mountain PBS, this was because zip codes had yet to exist, and postage at that time would have been, “COL” for Colorado and “CAL” for California. The chance of bad handwriting was high, along with traveling a few hundred miles to the wrong place.

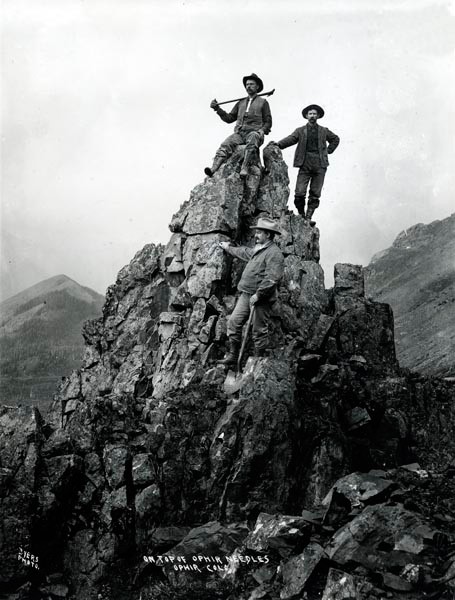

So, Telluride found its name in 1883 when prospectors thought they’d found actual Telluride, a type of rich gold ore. It ended just being regular ore, but the name kept for wishful thinking!

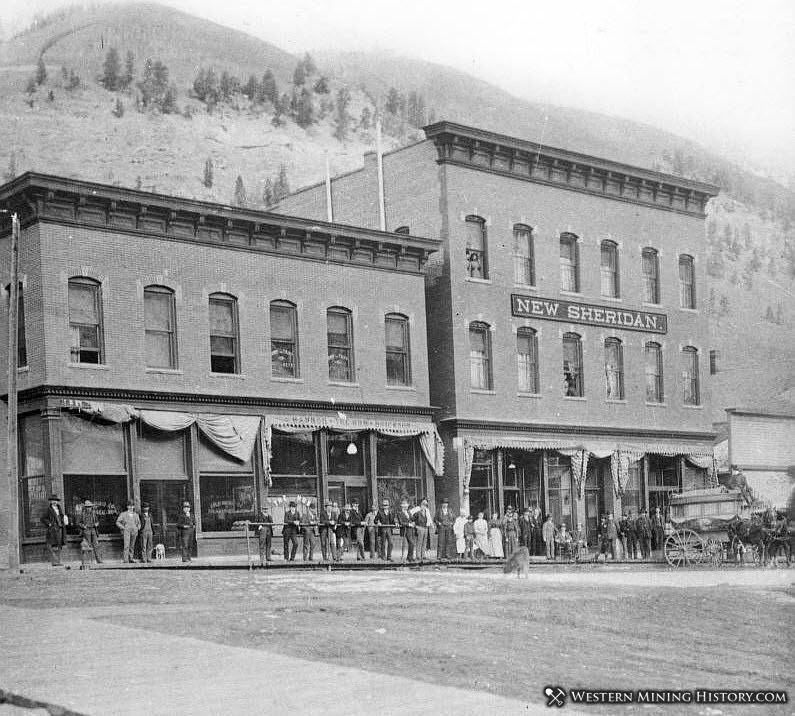

Aside from its proclivity for devastating avalanches (one in 1883 that killed 8 miners, and another in 1906 that killed 12), Telluride had its own especially wild attributes. When the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad made it to the miner’s hub in 1890, the townsfolk would occasionally shoot at the train. For what reason, entertainment most likely. This prompted the conductor to start warning unsuspecting passengers to get down on their way into the gorgeous box canyon, as it became “to hell you ride.”

Other businesses were just as vulnerable to random and unnecessary crossfire. Like the Sheridan Hotel, who listed on the house rules in the lobby to not shoot the piano player or ride one’s horse up the stairs, per Telluride TV. Or the San Miguel National Bank, who hosted Butch Cassidy’s first and largest robbery in 1889. The bandits made out with $30,000, a value more than $880,000 in 2021.

The mines of Telluride were also where the world’s first single-phase alternating current power transmission system was created for commercial use. The hydro-electric endeavor took place in 1891 by Lucien Lucius Nunn at the Ophir mining camp above Telluride. Telluride would get electricity through town three years later.

Like Ouray, Telluride was able to withstand the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act due to its golden veins, per Western Mining History. Then in 1940, Telluride’s mines switched from gold and silver to zinc, lead and copper to supply the military with artillery during World War II.

Mining in Telluride finally ceased in 1970. It was on the brink of becoming a complete ghost town, until its world-renowned ski resort began taking shape within the following years.

Creede – The Last to Boom

Creede is considered the last of the boom towns to reverberate throughout the San Juan Mountains. The town had a later start to its mining years, which began in 1890 and lasted (periodically) until 1985.

According to Rocky Mountain PBS, Creede’s later start may have been due to the assassinations at Wagon Wheel Gap. This is a cliff-lined section on the way into Creede, and was a fine place for Utes to shoot trespassers from above. As a courtesy to the future wagons coming through, the tribes would string up the others along the canyon walls.

Creede was founded by Nicholas C. Creede, a veteran who came across a silver vein in Willow Canyon. Once Nick staked his claim in the winter of 1890, the iced chasm began to flood with more miners than anywhere else in Southwest Colorado.

Creede’s mining area grew to 10,000 people within a couple years, and had plenty of misconduct that came with the literal territory. It was known to be the destination of runaway criminals from Denver, where gambling schemes came with creative twists, per Western Mining History.

Bob Ford, the man who killed Jesse James, started a saloon in Creede and was a bit of an unliked ruffian around town. While Bob was opening up the saloon alone one day, the hothead town marshal, Ed O Keeley, gave the greeting “Hello Bob.” Bob turned around, and Ed fired his shotgun through his jugular and nearly took his head off.

The event was so popular once word got out, crowds of townsfolk came for a group photo in front of Ford’s saloon the following day. You can even find a mural depicting the event Parks and Recreation style at the Creede Historical Museum & Library.

And if being outside of the mines was hard, going to work was more than hell. All mining towns suffered from tragic accidents, but this excerpt from the Times-Sun in Creede is especially telling of the commonality and gruesomeness of mining catastrophes:

Denver, August 24.—A special to the Times-Sun from Creede says;

Four miners in the Amethsyt mine were mashed, burned and boiled to death to-day…The fire, starting in the dry room between 3 and 4 a.m., burned the shaft house and all the machinery. The skip fell, crushing the above named unfortunates. Loss by the fire, $20,000. The mine is now filling with water.

Like Telluride, Creede had so much lead that it was able to contribute ammo for WWII. Following the war, an ore vein was discovered in the 60’s at the Bulldog Mine and ran operations there until 1985 when the price of silver plummeted once again.

More Reading

The Best Colorado Summer Road Trip – Denver to Durango Loop

Top Reasons Why You Need to Take a Jeep Tour in Southwest Colorado