Powell’s expedition through Lodore Canyon. This is part one of a three-part series re-tracing John Wesley Powell’s 3-month expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers; a series and story that we will tell in a style akin to Powell’s own descriptions of the expedition. Powell’s 1869 trip was a government-sponsored expedition to explore the rivers of the west, including the first government-sponsored passage of the Grand Canyon. In this part, we explore the challenges Powell and his crew faced as they traveled through the same canyons our multi-day trips travel down to this day. For this first part of the series, we recount the start of the expedition through Lodore Canyon on the Green River. In parts two and three we will explore what happened on the Powell’s exhibition through Desolation and Cataract Canyons.

Here’s a little tale about John Wesley Powell’s tribulations through Lodore Canyon on his 1869 expedition.

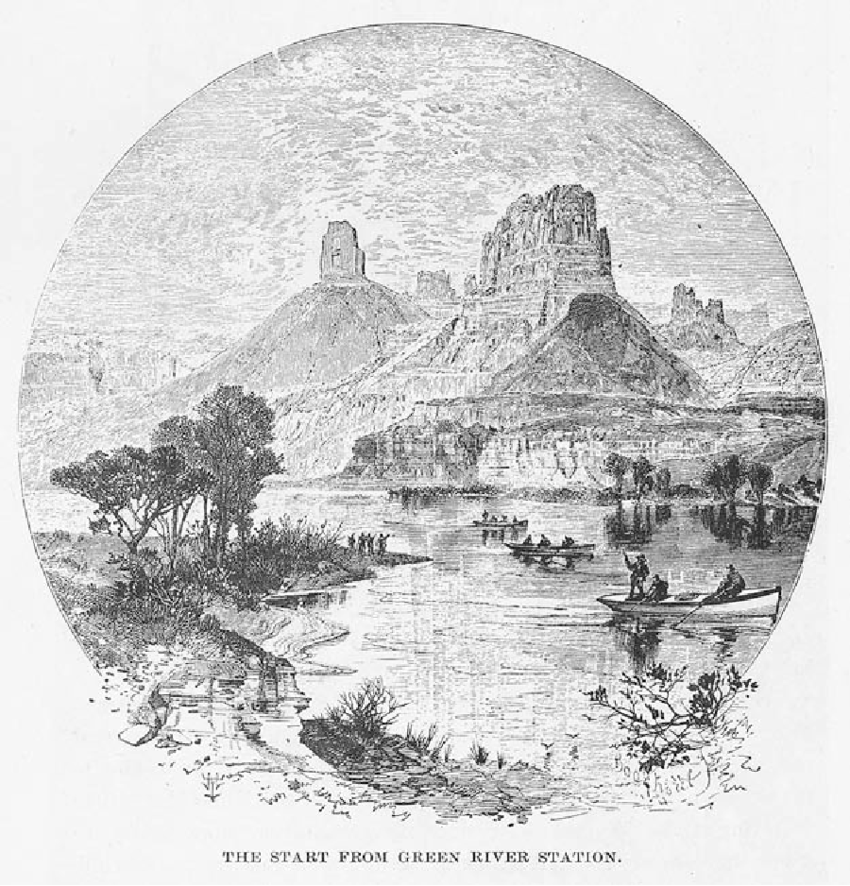

It was the summer of ‘69… 1869 that is, when a crew of ten men with four boats pushed off on a Wyoming river. Its waters would lead them through the last uncharted territories of the American West. It was also spring, just to keep things accurate.

They knew this river of green would eventually meet the Colorado, and then that river would eventually meet the Gulf of California. That was mostly the extent of what they were privy to expect.

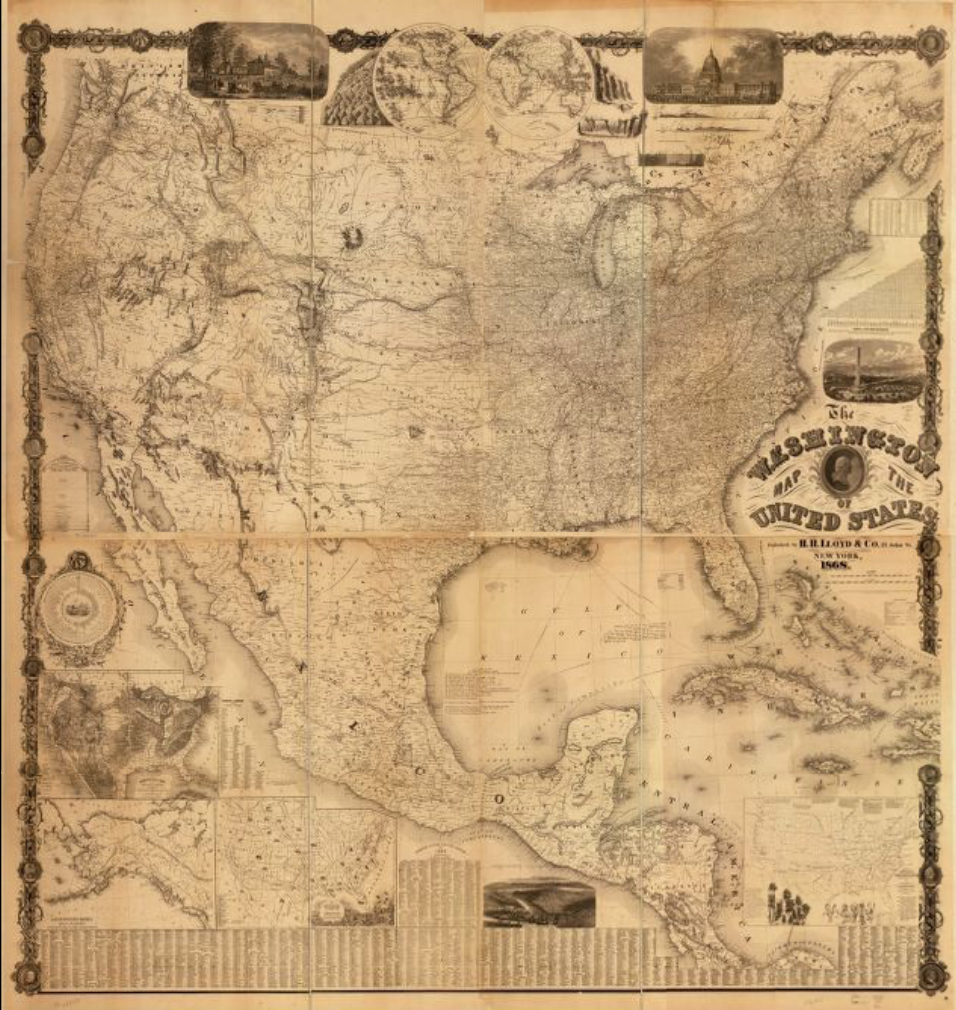

Much of everything in between was called “The Great Unknown” (named by Lewis and Clark) across government maps. For all people knew at the time, those depths of alien wilderness led to gardens of Eden and vanished underground.

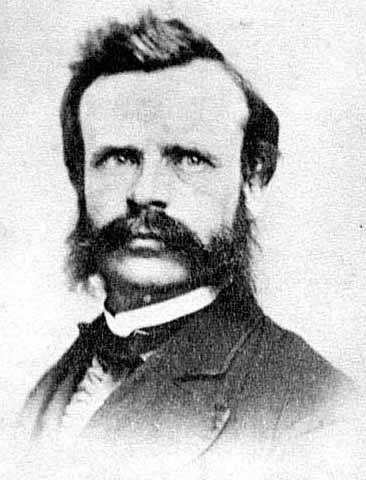

The expedition’s leader was John Wesley Powell, a 35-years-old Civil War veteran who had lost half of his right arm fighting for the Union North. This was not his first showdown with a wild river by far, nor was it his first research expedition in the Colorado Plateau.

Powell was an educator who was mostly self-taught in cartography, anthropology, and natural sciences. However, his background in independent research made him a worthy-enough candidate for the largest expedition this burgeoning nation had seen yet.

Along for the survey were some of the sturdiest bunch of guys to have ever lived. All were fellow veterans (except one who was a deserter) and thus more fit for the life-threatening endeavor ahead than for the scientific purposes of the trip. They weren’t in this to make maps and gather specimens, they were there to know The Great Unknown.

At the beginning of the expedition, the Green River was quick but kind to the new rowers. Their introduction started in “Country worthless” as member Jack Sumner put it. Even the portals of Flaming Gorge and Brown’s Canyon allowed the group gentle boating practice, which was a blessing yet to be realized as the expedition entered the Gates of Lodore.

June 8, The Disaster that became Disaster Falls

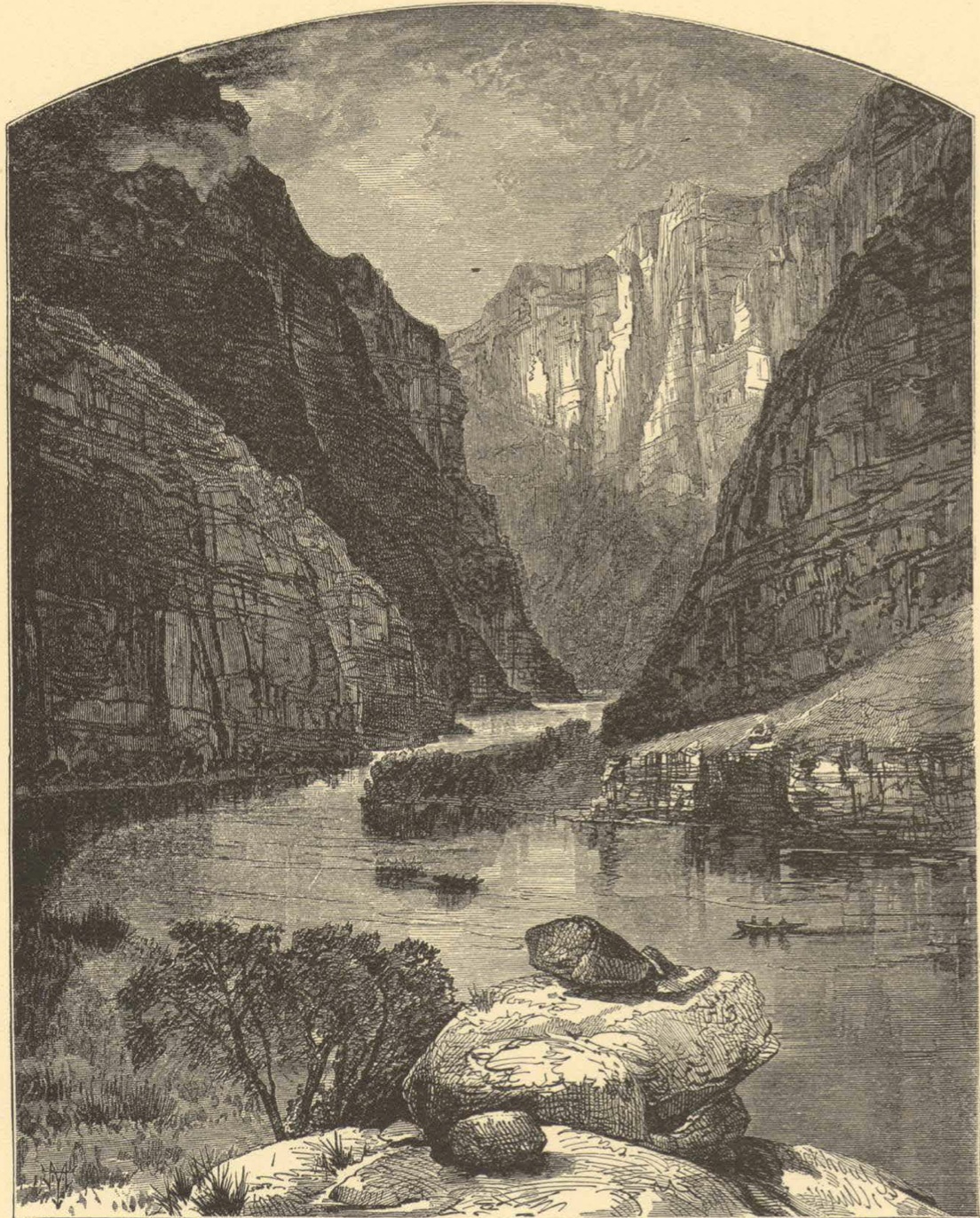

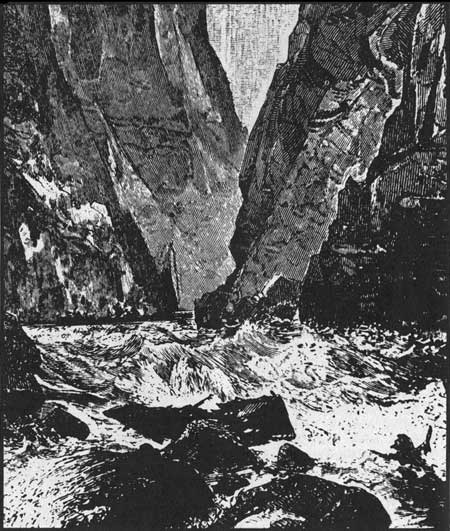

The ingress of Lodore Canyon resembles Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Standing in billion-year-old quartzite, the gates to this crimson chasm rise 2,000 feet directly above the Green River.

Within three miles, the glassy emerald waters turned to rolling strands of pearls, which the crew cheerfully crushed with their oars throughout the morning.

Powell always led the fleet in the smaller pilot boat the Emma Dean, named after his wife. When they came to a bouldered section now named Winnie’s Rapid, Powell waved a red flag signaling for the others to port. Drama-free, they lined the boats through the waves and were back on the river in a jiffy.

Lining involves tying the stern of a boat to the shore below the rapid while the crew guides its bow line above the rapid. This allows the boat to run the rapid in control (in theory) from the shore.

Shortly after Winnie’s, Powell saw the rolling pearls began to shatter into jagged, boat-murdering diamonds ahead. He signaled to port again.

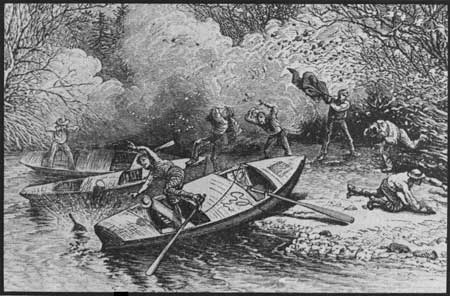

In came Emma Dean, then Kitty’s Clyde Sister, and as Maid of the Canyon joined the convoy, the No-Name went breezing by to everyone’s devastation.

Aboard were the burley Howland brothers and gentle Englishman Frank Goodman, who had missed the signal in time. They began frantically bailing and pulling their swamped skiff, but with worthless effort by then. It was incredibly too late for even the strongest men to escape this canyon-cutting current.

And so, 21 feet of oak dropped into the first rapid, lined up to perfection for the first boulder. Bow to the bull’s eye, the three men soared into the air before their baptism in cataclysmal froth.

Somehow, they managed to swim back to the skiff before it rushed downstream for the next boulder. This time it swung broadside with a death wish, and with impeccable aim the rock snapped the boat “quite in two” as Powell put it.

In the middle of the roaring white was an islet for the Howland brothers to seek refuge. For quite polite Goodman, he found a mostly submerged rock foaming in a whirlpool, but to its credit had kept him from drowning. He was luckily nearby the islet too, and with a salvaged pole from the quickly disappearing No-Name, a Howland saved the red-faced gentleman in time.

As the three remained in the middle of the Green River’s sassiest moment yet, business had been already carrying on from shore. The rest of the crew lined the other three boats while the survivors watched what was left of their craft finally surrender to the undercurrent.

Jack Sumner then hopped in the Emma Dean to rescue the soggy survivors. His skillful maneuvering proved to be the best of the bunch, and all arrived to shore safely.

Powell wrote, “We are as glad to shake hands with them as though they had been on a voyage around the world, and wrecked on a distant coast.”

However Powell’s relief wouldn’t last long. In the No-Name was a third of the 10-month food supply, the three men’s additional belongings, a few guns, and most importantly— the barometers. Without these instruments, the expedition had lost its entire purpose to map The Great Unknown.

Powell understandably didn’t sleep that night. He considered climbing out of the canyon and walking the more than 200 miles to Salt Lake City to retrieve more barometers to save the expedition. He did not.

June 9, Salvaged Spirits

The next day, they found remnants of the boat splattered against another boulder downstream. Jack Sumner and Bill Dunn hopped in the Emma Dean for another rescue mission in hopes to recover Powell’s precious hardware.

Powell wrote:

They start, reach it, and out come the barometers; and now the boys set up a shout, and I join them, pleased that they should be as glad to save the instruments as myself. When the boat lands on our side, I find that the only things saved from the wreck were the barometers, a package of thermometers, and a three gallon keg of whisky, which is what the men were shouting about.

Powell was so elated about his beloved barometers, Jack Sumner likened him to a smitten teenage girl. As for the juice, Powell didn’t know about it and had been previously opposed to having alcohol on the trip. But given the circumstances, he allowed it to come along as “medicine.”

June 17, Hawkins Started the Fire

At this point, the expedition had been portaging rapids in Lodore Canyon for over a week. The crew was battered, burnt to a crisp, and thoroughly sanded down to a normal person’s breaking point. Camp that night was on a small beach in a groove of dead willow trees and cedar.

The crew adorned the dry branches with their always-wet wool while young Billy Hawkins made coffee over the fire. As the men chatted in the twilight, a gust came in stampede. In a mere moment, the whip cracked the cook’s embers and transformed the evening into complete cockamamy.

It was Hades on the beach. But luckily, for the first time in Lodore Canyon, there was the river! They rushed to it with gratitude, their beards and trousers flaming.

Billy had stacked the majority of the cooking supplies in his arms, but as he raced to the banks, slapstick prevailed and he tripped. The mess kits were now tributes to the tributary as it was time for everyone to push off.

In the dark and in every direction, the boats bumbled into an uncharted rapid. Luckily the water wasn’t as saucy as it was upstream, and they blindly ran it with success. They laughed heartily, especially when they realized General Bradley’s eyebrows had joined their losses that night.

Powell wrote, “Our plates are gone, our spoons are gone, our knives and forks are gone; “Water ketch’ em,” “H-e-a-p ketch’ em.” His quote came from the Utes who had previously warned the expedition about the unforgiving ways of this river.

June 18, Powell Needs Pants

Powell wrote:

We run down to the mouth of the Yampa River. This has been a chapter of disasters and toils, notwithstanding which the canyon of Lodore was not devoid of scenic interest, even beyond the power of pen to tell. The roar of its waters was heard unceasingly from the hour we entered it until we landed here. No quiet in all that time. But its walls and cliffs, its peaks and crags, its amphitheaters and alcoves, tell a story of beauty and grandeur that I hear yet and shall hear.

The food was already sour from relentless wetting, and their skin was peeling in shreds when they reached Echo Park. Its wide meadows and calm waters was the closest Eden they’d seen yet. It meant game, and well-deserved rest.

For Powell, the cliffs of the Mitten Park fault curled with geologic poetry that recited prehistory. For Jack Sumner, the monolith now named Steamboat Rock (they named it Echo Rock at the time), was the prettiest he’d ever laid eyes on. And because it was indeed magnificent, Powell would need to survey it.

Powell wrote:

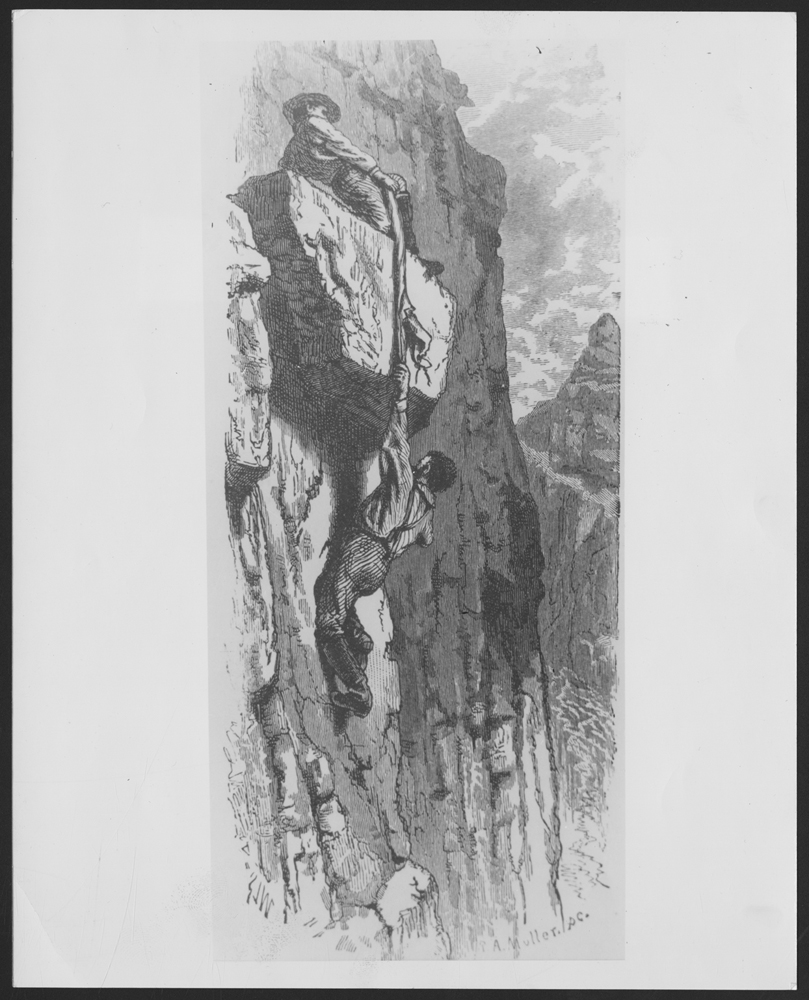

Looking about, we find a place where it seems possible to climb. I go ahead; Bradley hands the barometer to me, and follows. So we proceed, stage by stage, until we are nearly to the summit. Here, by making a spring, I gain a foothold in a little crevice, and grasp an angle of the rock overhead. I find I can get up no farther, and cannot step back, for I dare not let go with my hand, and cannot reach foot-hold below without. I call to Bradley for help. He finds a way by which he can get to the top of the rock over my head, but cannot reach me. Then he looks around for some stick or limb of a tree, but finds none. Then he suggests that he had better help me with the barometer case; but I fear I cannot hold on to it. The moment is critical. Standing on my toes, my muscles begin to tremble. It is sixty or eighty feet to the foot of the precipice. If I lose my hold I shall fall to the bottom, and then perhaps roll over the bench, and tumble still farther down the cliff. At this instant it occurs to Bradley to take off his drawers, which he does, and swings them down to me. I hug close to the rock, let go with my hand, seize the dangling legs, and, with his assistance, I am enabled to gain the top.

June 22, “The Clouds are the Artists Sublime”

After leaving paradise, they quickly met “a gloomy chasm, where mad waves roar” which would later be named Whirlpool Canyon. By the name, they went spinning and walloping against the canyon’s walls with no beach to rescue them. When they could, they would climb the ledges above the water to line the boats precariously from above.

When they reached the bizarre passage of Split Mountain (aka Craggy Mountain at the time), Powell asked then as geologists do now; Why Green River, did you choose to cut these mountains in two rather than go around them?

What Powell did understand is that mountains form from “internal geologic forces that fashion the earth” and that weather tremendously shapes their progress further. He said, “We think of the mountains as forming clouds about their brows, but the clouds have formed the mountains.”

June 28, Out of the Rocks… for now.

They covered thirty miles in a day without any problems, coming to the Uintah, or Wonsits, Valley where Powell and other explorers had passed through before. They met the mouth of Duchesne River, and up its stream was the last known civilization near the Green River. Frank Goodman called it quits upon arrival, and the rest were fine to move on without him given their dwindling food supply.

This would bring their run through Lodore’s crimson, Echo Park’s cream, and Split Mountains midnight-colored canyons to a close. Downstream promised Desolation Canyon and much more adventure, which you can continue reading about in part two of this series.

More Reading: