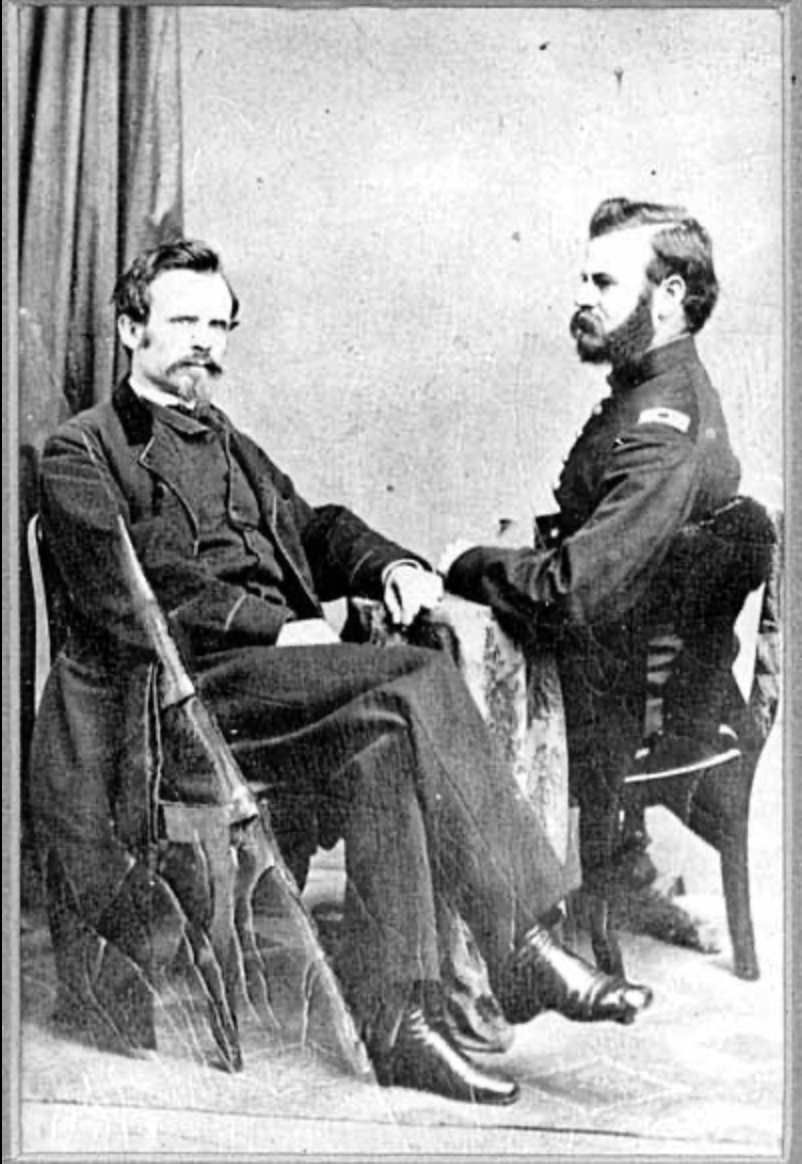

Powell’s 1869 expedition through Cataract Canyon. This is part three of a three-part series re-tracing John Wesley Powell’s 3-month expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers; a series and story that we will tell in a style akin to Powell’s own descriptions of the expedition. Powell’s 1869 trip was a government-sponsored expedition to explore the rivers of the west, including the first government-sponsored passage of the Grand Canyon. In this part, we explore the challenges Powell and his crew faced as they traveled through the same canyons our multi-day trips travel down to this day. For this final part of the series, we recount the journey through Cataract Canyon on the Colorado River. In parts one and two, we explored what happened on Powell’s expedition through Gates of Lodore & Desolation Canyon.

After journeying 538 miles down the Green River, the nine-man crew floated their three wooden boats out of Stillwater Canyon to meet the Colorado. Their odyssey began in Green River, Wyoming, where they began rowing into The Great Unknown to map what was left of the immaculate Wild West.

They were a bewilderingly resilient pack of Civil War veterans ranging from 18 to 35 years-old. After Lodore Canyon’s frothing beasts and fires, Desolation Canyon’s ominous heights, and two months of rotten meals, the unsuspecting crew was surprisingly prepared for the upcoming chaos.

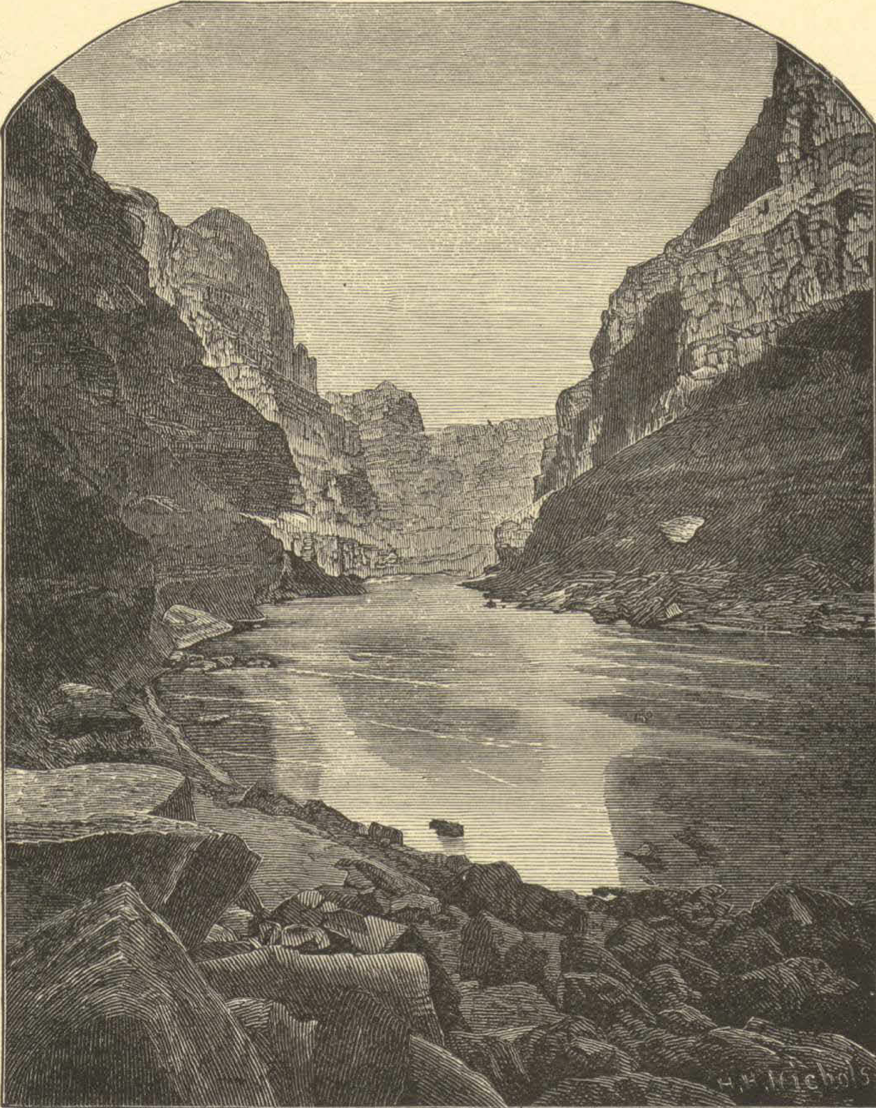

Cataract Canyon would greet Powell’s 1869 expedition with unwelcomed warmth, scenes steeped for poetic pennings, and the most petrifying hydraulics this side of the continent. The Colorado River was what they’d come for, and this canyon was the portal to the only thing they knew to be waiting on the other side— the Gulf of California.

July 16th, Junction City

“Hurra! Hurra! Hurra! Grand River came upon us, or rather we came upon that very suddenly and to me unexpectedly at 5 ½ P.M,” George Bradley wrote, in the most indicative expression for this defining moment of the expedition.

Powell’s entry that day seemed a little wearier, as the “solemn depths” of these great rivers combined ensured more power, and thus, bigger and fatter waves in their continued descent.

Jack Sumner’s entry couldn’t help but make mention of a river gabbling phony from a Colorado newspaper who had “…went so far as to claim that he had laid out a town and called it Junction City. Where he had is Burgh is more than I can say as it is an apparently endless Canon in three directions…” But the crew kept the name for the confluence no less.

Given the destination’s significance, the men camped here for the next few days to take measurements and observations. They would also need to re-caulk their oak crafts for what Powell rightly predicted “a vigorous campaign.”

Bradley was also privy of what was to come as he had become quite the canyon reader; “It is possible we are allured into a dangerous and disastrous canon of death by the placid waters…”

July 17th, Sour Flour

Less than two weeks and 334 miles earlier, Powell acquired 300 pounds of flour to replenish a fraction of what was lost in the No-Name— the expedition’s fourth boat that was pulverized and drowned by Lodore Canyon’s whitewater. Today, only a third of the flour was found usable after sifting out the mold through a mosquito net.

George Bradley wrote, “We have only 600 lbs left and shall be obliged to go on soon for we can not think of being caught in a bad canon short of provisions.”

And you know things are bad when folks start to squawk at bacon… although theirs was decomposing. Canyons make it understandably difficult to hunt, and the Green River’s catfish were so unappetizing, they quickly became unworthy of their efforts. Bagging even the occasional elderly goose had become reason to rejoice.

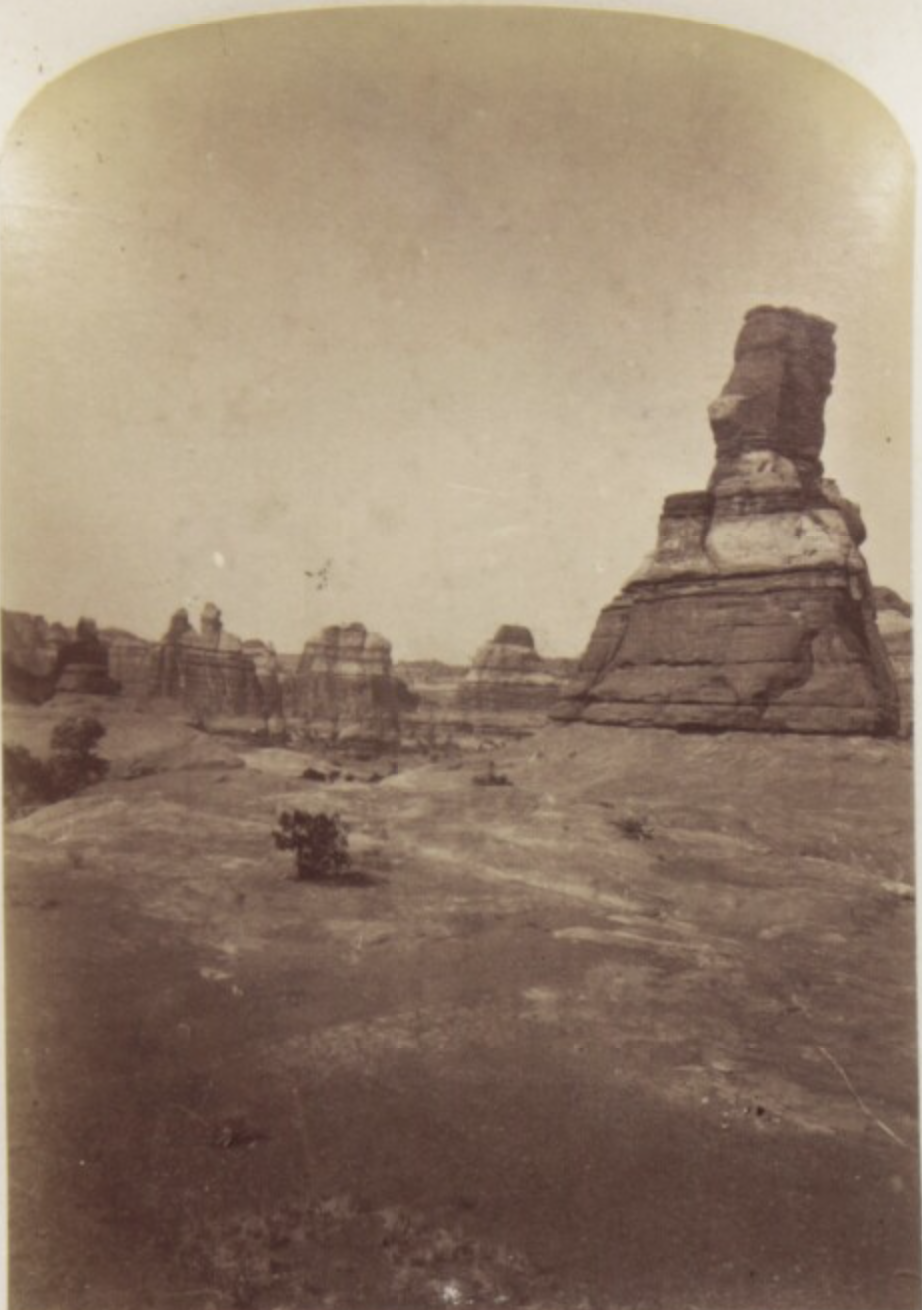

July 19th, “…Ten thousand strangely carved forms in every direction; and beyond them, mountains blending with the clouds.” — John Wesley Powell.

Major Powell and General Bradley’s usual precarious climbs commenced that morning from the junction. The men trimmed the ledges, at times on their bellies 800 feet above the river, and ascended vertical crevices “as men would out of a well” Powell recalled through a network of caves.

The passages eventually led to the canopy where the Earth swept into an exclusive moment of eternal observability. Bradley described the display as “the same old picture of wild desolation we have seen the last hundred miles.”

This was indicative of George’s general feelings about the desert, as he was neither fond of its impeccable silence nor mirage-making heat.

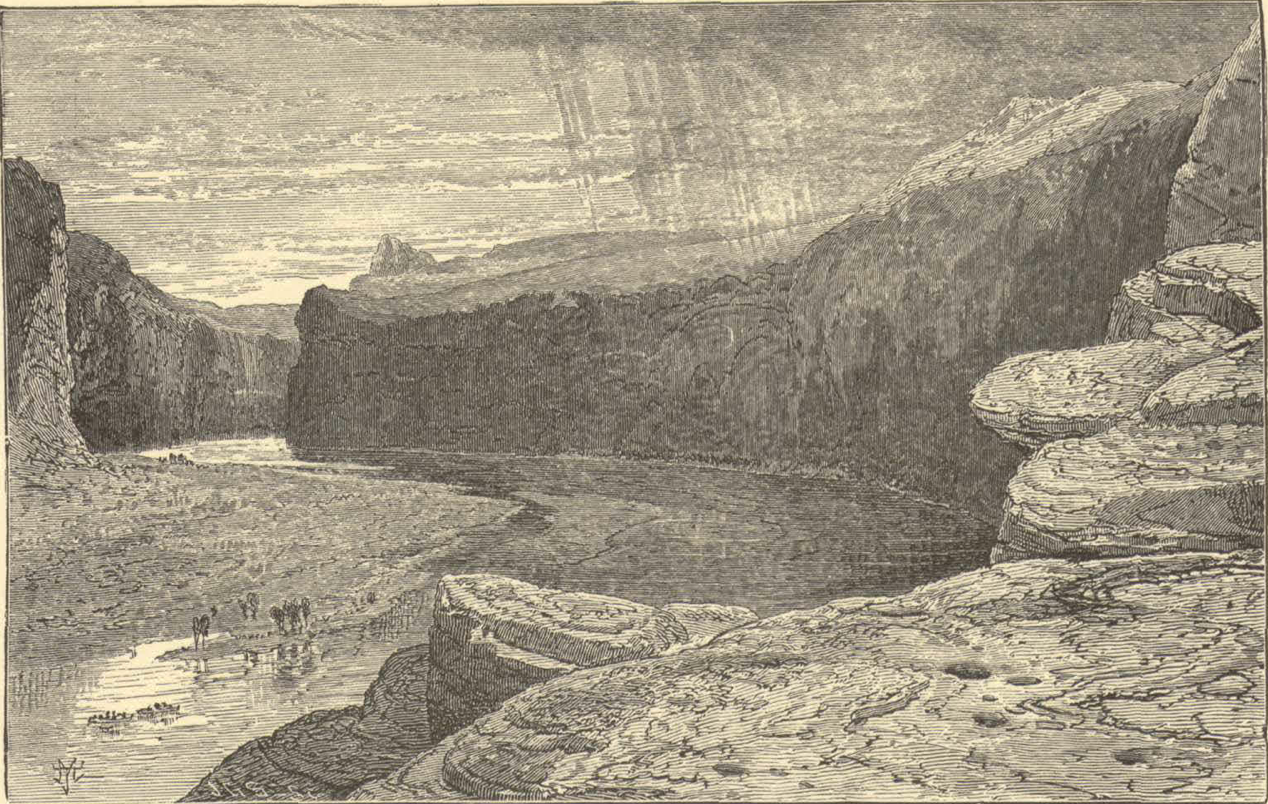

But for Powell, these ancient imprints of three colliding rifts, rolling in from the snow-capped peaks of the La Sals were soul-stirring. The area where he and Bradley stood is today’s Confluence Overlook in the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park.

Powell wrote,

“Now we return to camp. While we are eating supper, we very naturally speak of better fare, as musty bread and spoiled bacon are not pleasant. Soon I see Hawkins down by the boat, taking up the sextant, rather a strange proceeding for him, and I question him concerning it. He replies that he is trying to find the latitude and longitude of the nearest pie.”

July 20th, Bros on the Wall

Today Powell and his brother William would survey the western portion of the confluence, “for the purpose of examining the strange rocks seen yesterday from the other side,” Powell said.

This side of the climb was to the mouth of the Grand River, which was renamed to be the continuation of the Colorado River in 1921. At the top, their bird’s eye view would come with crevices perhaps as deep as the goose-necked monolith on which they stood. They leapt across most of them until they became too wide to chance it— which considering their superlative physicality, was probably pretty damn wide.

“It is curious how a little obstacle becomes a great obstruction when a misstep would land a man in the bottom of a deep chasm. Climbing the face of a cliff, a man will walk along a step or shelf, but a few inches wide, without hesitancy, if the landing is but ten feet below, should he fall; but if the foot of the cliff is a thousand feet down, he will crawl.”

July 21st, “So I conclude The Colorado River is not a very easy stream to navigate.” — George Bradley

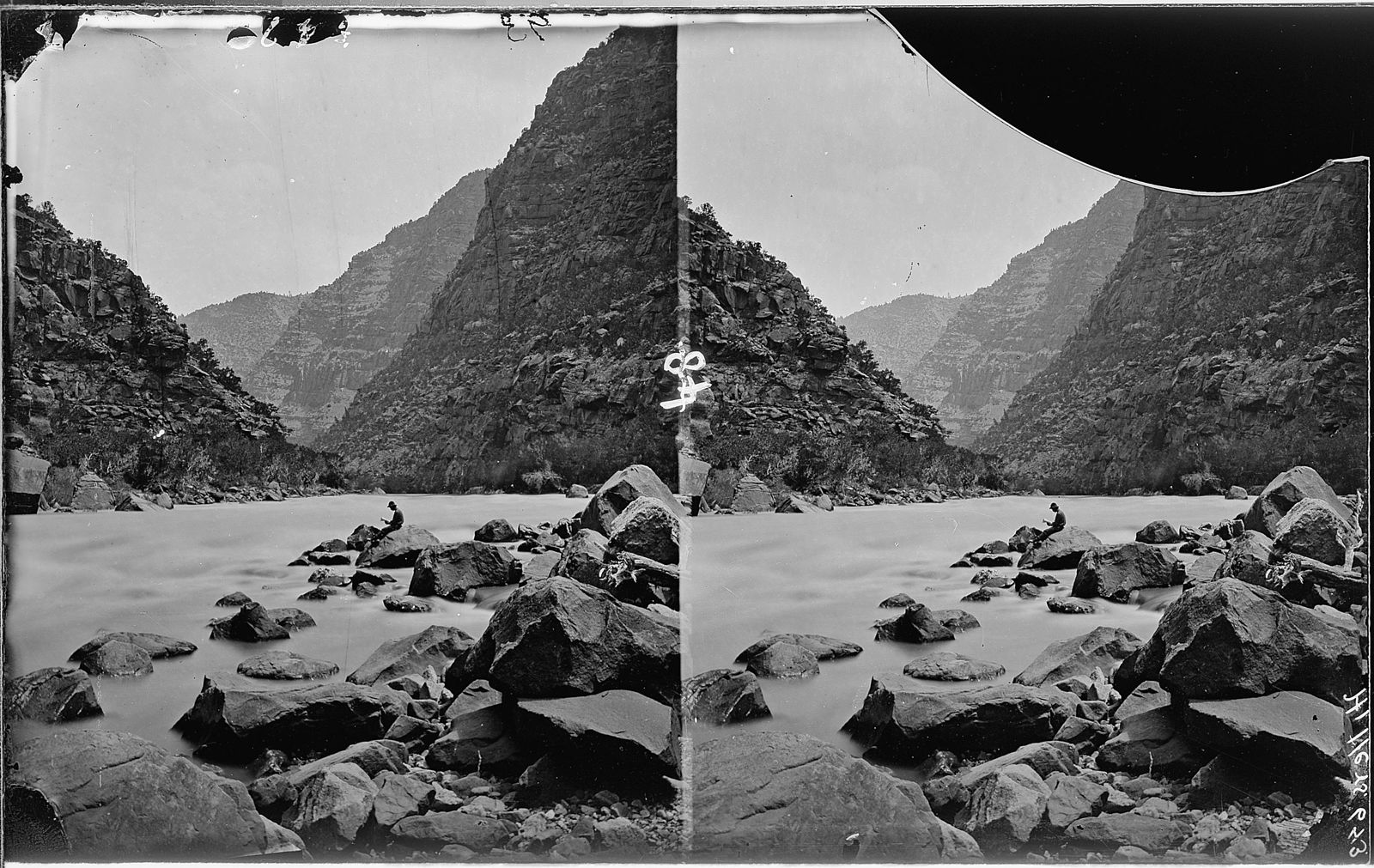

Just a few miles from Junction City, the runway for the West’s biggest whitewater begins with an amicable entrance.

The first section of class III waves are known today as The Slide. The men ran it, but would quickly take to the shore again after Brown Betty Rapids for the most irritating portages of the expedition yet.

Brown Betty, aka Rapid 1, is named after the Brown-Stanton expedition who surveyed the Grand Canyon in 1889.

After lunch, Emma Dean dunked Powell and the other boys aboard, as was her tendency since Desolation Canyon. It cost them three oars and another painstakingly long and laborious session of unloading soggy flour, underused ammunition, and fragile barometers.

At least they made 8 ½ miles. However, they didn’t seem to appreciate it much after having to make camp on a stack of busted boulders that night.

The following morning was an “off” day to remake oars from driftwood and survey the sliding strata now known as the Paradox Formation. Its folds were bizarre enough to strike even a geologic interest from the usually-uninterested crew members.

Understandably so, since this ornate layer is seldom seen. The Paradox Formation was formed by an ancient sea that flooded and evaporated 29 times across a now parched landscape. It left behind a super-old layer of sea salt that is periodically liquified under pressure. Given this is a base for the much sturdier rocks above, it gives this area of Utah fabulous diagonals.

July 23rd, Hidden Treasure through Mile Long Rapid

“On starting, we come at once too difficult rapids and falls, that, in many places, is more abrupt than in any of the canons through which we have passed, and we decide to name this Cataract Canon.” Powell wrote.

John might be describing Rapid 5 given it comes with two very mouthy holes at low water. The crew continued their lug for the following mile, tripping along the shoreline past mystic monikers like the North Sea at rapid 7.

“Major estimates that we shall fall fifty feet on the next mile and he always underestimates,” Bradley justifiably fussed about the river’s ever-growing giants.

When the men stopped for lunch, a few went for a rendezvous up a side canyon, perhaps somewhere near Range Canyon according to Powell’s following description;

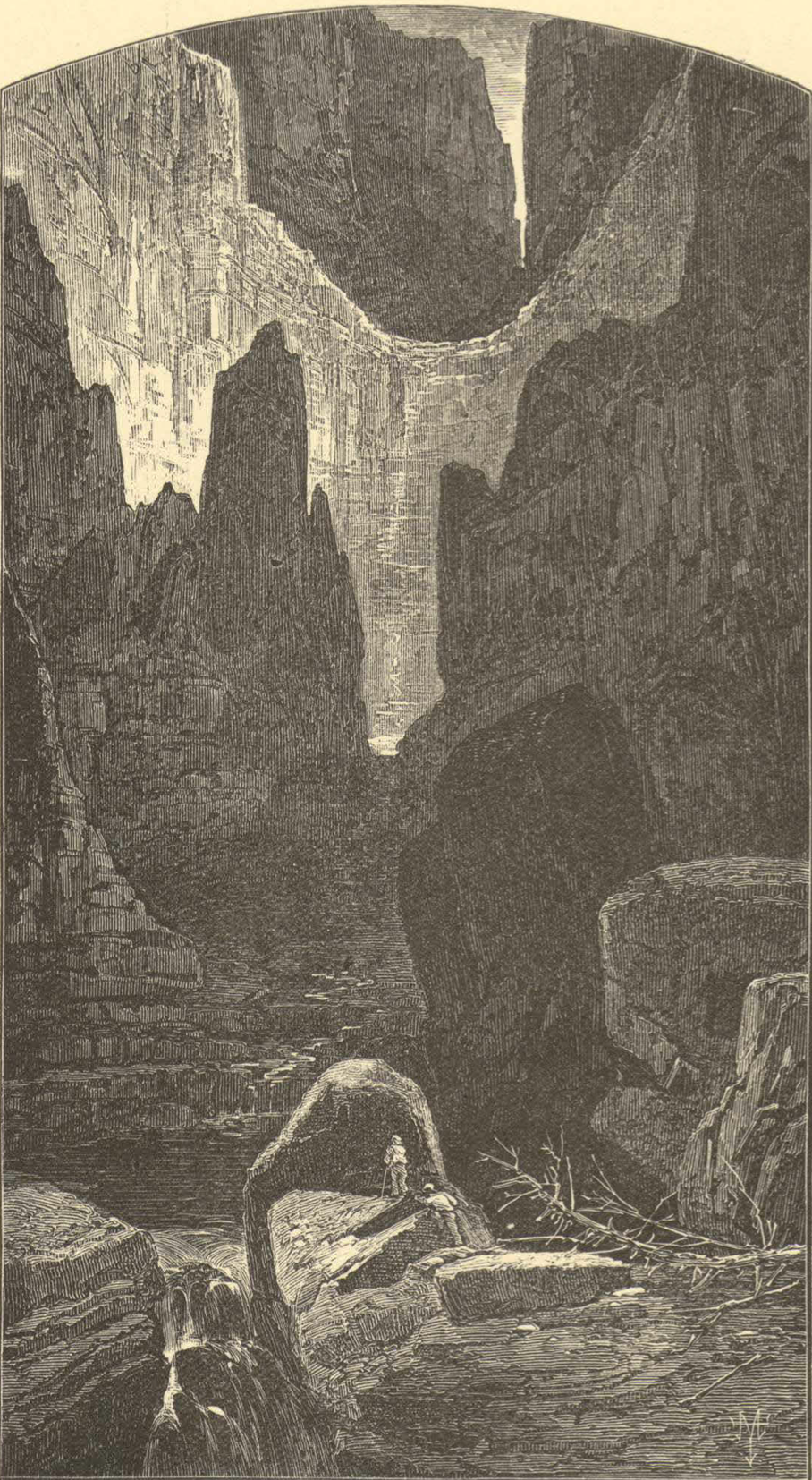

“What a chamber for a resting place is this! hewn from the solid rock; the heavens for a ceiling; cascade fountains within; a grove in the conservatory, clear lakelets for a refreshing bath, and an outlook through the doorway on a raging river, with cliffs and mountains beyond.”

It would be a shorter day with 5 ½ miles on the docket but without relief. They pondered if these growing holes and drops would soon become complete waterfalls.

Powell wrote,

“Such places have been found, except that the falls were not so great but that we could run them with safety. How will it be in the future! So they speculate over the serious probabilities in jesting mood, and I hear Sumner remark, ‘My idea is, we had better go slow and learn to peddle.’”

July 24th, “God help the poor wretch that is caught in the canon during high water.” — Jack Sumner

Around ten thousand years ago, Cat’s walls puked up a fine portion of talus. While Powell wasn’t then certain of their age, he took an astute note of the slopes that were responsible for the violent terrors convulsing before them. Meanwhile, Jack Sumner took an also astute note of the driftwood 30 feet above the shoreline.

The portages were horrendous as usual. Class III and IV carnage and rubbled banks of bullshit ripped the resin from the three boats’ freshly water-sealed compartments. It took so much time that when night fell, they’d made less than a mile’s progress through Mile Long Rapid.

The camp that night was sprawled above the Big Drops. Powell sat in the twilight watching and listening to the river glut its own glowing creations.

Powell wrote,

“Where there are sunken rocks, the water heaps up in mounds, or even in cones. At a point where rocks come very near the surface, the water forms a’chute above, strikes, and is shot up ten or fifteen feet, and piles back in gentle curves, as in a fountain; and on the river tumbles and rolls.”

The crew scouted the rapids while Bradley kept to camp. “They don’t interest me much unless we can run them. That I like but portage don’t agree with my constitution,” although he conceded that Big Drop One was absolutely incomparable to anything they’d seen before.

July 25th, Emma Dean Runs Big Drop One

Perhaps from heat exhaustion, or whatever extraordinary reason, Powell decided to put his petite pilot boat to the test in the smallest of the largest rapids on the Colorado River.

It is safe to assume that water levels were low-ish (in terms of Cataract) given it was late July. Even so, maneuvering Big Drop One in an inflatable raft, let alone in oak skiffs hardly high enough to cast a reflection, can make anyone need a change of trousers.

Somehow, someway, the boat managed to break through waves only to be caught in a whirlpool that politely traded the men’s lives for an oar.

Indicatively, Powell’s journal entry was as brief as Jack Sumner’s this day, showcasing the endeavor of the Big Drops. They gained 3 ½ miles, conquering all three of Cataract Canyon’s whitewater-breathing monsters.

July 26th, Powell’s Crackin’ Up in Gypsum Canyon

It was time for more maintenance and sealing for their three busted boats. The hunt for resin began first thing on another 90-degree morning.

Before those thirsty tamarisks came along, Cataract Canyon’s drastic geology and climate made hearty vegetation in short supply. But the men were able to spot some greenery hanging in the cliffs from camp.

After wandering through slot canyons, amphitheaters, and crystal clear pools, Seneca Howland, Andy Hall, George Bradley, and Powell’s brother Walter came to the last promising approach with the Major. It was still too vertical for a confident scramble, so the group split up to find any promising routes through the red-rocked cathedral.

All of them chickened out except for the guy with one arm and a barometer on his back, who would shimmy himself up a fissure…

“…by pressing my back against one wall and my knees against the other, and, in this way, lift my body, in a shuffling manner, a few inches at a time, until I have, perhaps, made twenty-five feet of the distance, when the crevice widens a little, and I cannot press my knees against the rocks in front with sufficient power to give me support in lifting my body, and I try to go back. This I cannot do without falling. So I struggle along sidewise, farther into the crevice, where it narrows. But by this time my muscles are exhausted, and I cannot climb longer; so I move still a little farther into the crevice, where it is so narrow and wedging that I can lie in it, and there I rest.”

After taking a breather whilst levitating inside a stone closet, Powell continued his hoist to the summit.

There he found plenty of good pinons, but he was without a container. So John Wesley sliced off the unused right arm of his shirt and packed two pounds of resin into it. His applause came in the concession of an afternoon thunderstorm.

“I am thoroughly drenched, and almost washed away. It lasts not more than half an hour when the clouds sweep by to the north, and I have sunshine again.”

When Powell returned to camp, most of the guys were impressed with his loot. Except for Bradley. “… Major who says he climbed the cliff, but I have my doubts.”

July 27th & 28th, Oh sheep, it’s the Dirty Devil!

The men would run all but one of the day’s waves before noon. And not only would they bag rapids 26 through 29, but two Big Horned sheep were also made dinner that evening.

Bradley declared it as “the greatest event of the trip” while Jack Sumner agreed it was “A God-send to us as sour bread and rotten bacon is a poor diet for as hard work as we have to do.”

The next day would bring the longest portages they’d made yet on The Colorado River. But it wouldn’t last long as the river would calmly carry them for 12 ½ miles. The canyon walls would lower, bowing to Cataract’s end and Narrow Canyon’s beginning.

In the evening they would meet a stream that Jack Sumner candidly described, “…as filthy as the washing from the sewers of some large dirty city, but stinks worse than Cologne ever did.”

Powell wrote,

“One of the men in the boat following… shouts to Dunn, asking if it is a trout-stream. Dunn replies, much disgusted, that it is “a dirty devil,” and by this name, the river is to be known hereafter.”

July 29th, “Here I stand, where these now lost people stood centuries ago, and look over this strange country.” John Wesley Powell.

The men would enter a canyon that today rests under Lake Powell. It would hold the most precious archaeological findings of Powell’s 1869 expedition after Cataract Canyon.

There they would play in temples of moss-covered grottos and artifact-filled glens. The kivas were left so soundly, ashes still dusted the fire pits, arrowheads were sharpened as if yesterday and rickety ladders leaned against the walls.

“We decided to call it Glen Canyon. Past these towering monuments, past these mounded billows of orange sandstone, past these oak set glens, past these fern decked alcoves, past these mural curves, we glide hour after hour, stopping now and then, as our attention is arrested by some new wonder…”

Quickly thereafter came the Grand Canyon (where books are far more fit to even summarize this section of the expedition), and after that, the highly anticipated Virgin River where they would meet the journey’s end.

This concludes this series on the Powell Expedition of 1869 of the canyons Mild to Wild is so deeply fortunate to run. Without the courageous work of these men from more than 150 years ago, we wonder what our jobs would be like today. It is with great gratitude that we continue a legacy of discovery and wonder in these incredible canyons.

More Reading

Powell’s Plummet through Lodore Canyon – The 1869 Expedition

Powell’s Journey through Desolation Canyon – The 1869 Expedition