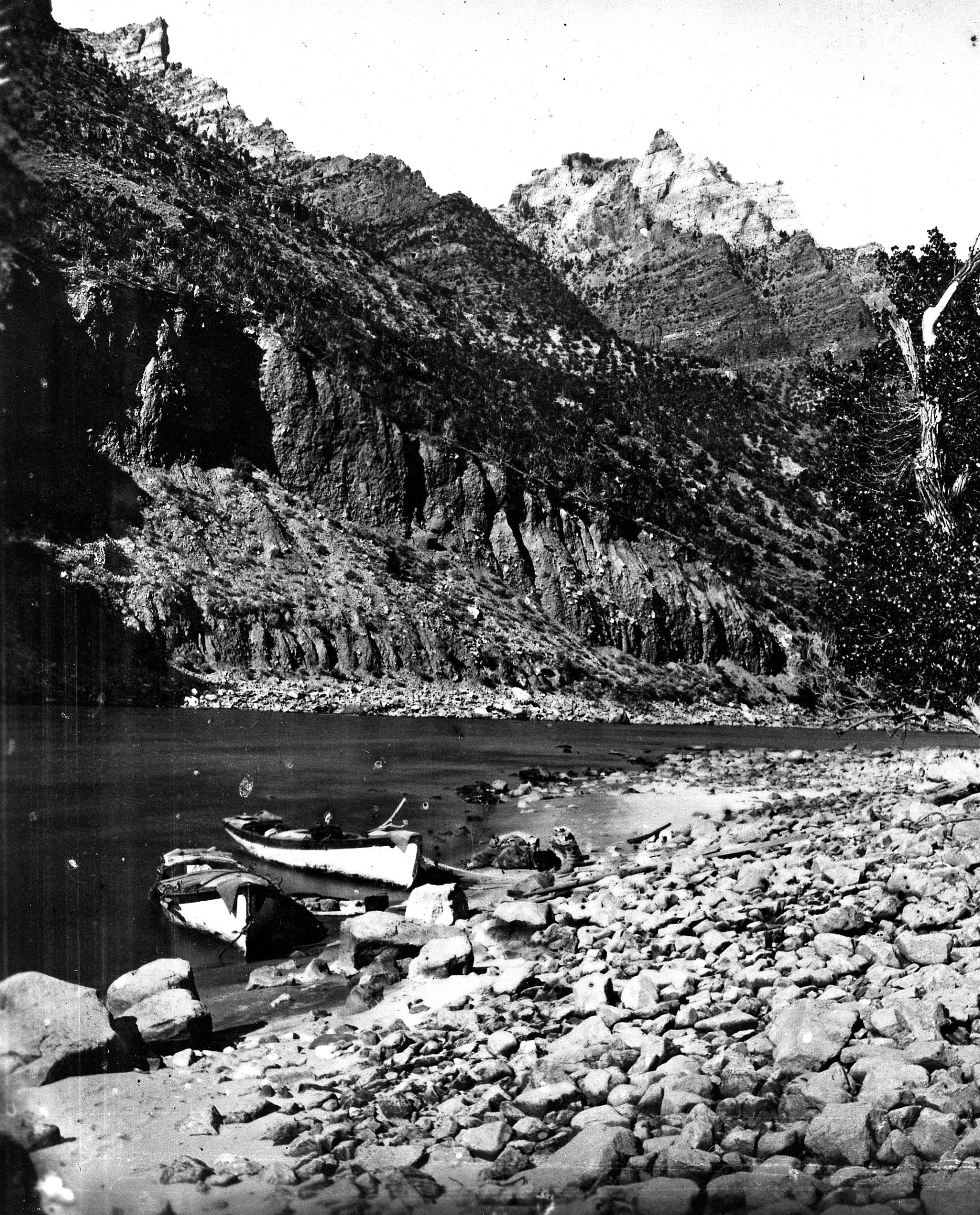

Powell’s expedition through Desolation Canyon. This is part two of a three-part series re-tracing John Wesley Powell’s 3-month expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers; a series and story that we will tell in a style akin to Powell’s own descriptions of the expedition. Powell’s 1869 trip was a government-sponsored expedition to explore the rivers of the west, including the first government-sponsored passage of the Grand Canyon. In this part, we explore the challenges Powell and his crew faced as they traveled through the same canyons our multi-day trips travel down to this day. For this second part of the series, we recount the journey through Desolation Canyon on the Green River. In part three we will explore what happened on Powell’s expedition through Cataract Canyon.

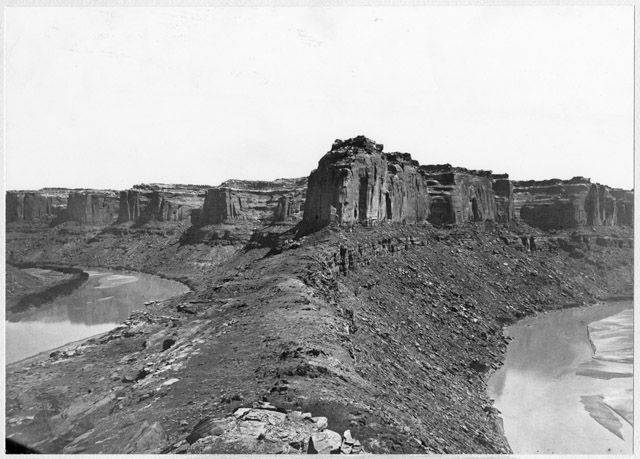

On June 27th, Split Mountain finally spit out the 1869 Powell Expedition with Desolation Canyon soon to come. Desolation remains nearly as remote today as it was in 1869, cutting through the largest wilderness area in the contiguous United States. It’s western Utah at arguably its gnarliest, and most beauteous.

By then they were three weeks into surveying the country’s last unexplored river canyons of “The Great Unknown.”

Already a third of their 10-month food supply— including the boat that carried it— belonged to the Green River. The crew, who began as a rugged-looking bunch, now had a new rabid makeover.

Their skin was sanded down as far as their patience, with beards and mutton chops cooked from a campfire gone wrong— although they had a good laugh about that particular mishap. They very much looked like the terrible work of carrying boats more than rowing them for 60 miles.

It was a widely publicized endeavor across the nation even before the expedition pushed off from Green River, Wyoming. And while it was certainly turning out to be a novel, the stories kept rolling in, despite the 10 men being indubitably far from any reporter’s reach.

This is part two of our series re-tracing the John Wesley Powell expedition through the canyons of Lodore, Desolation, and Cataract. For the previous chapter about the expedition’s chaotic beginnings, read here.

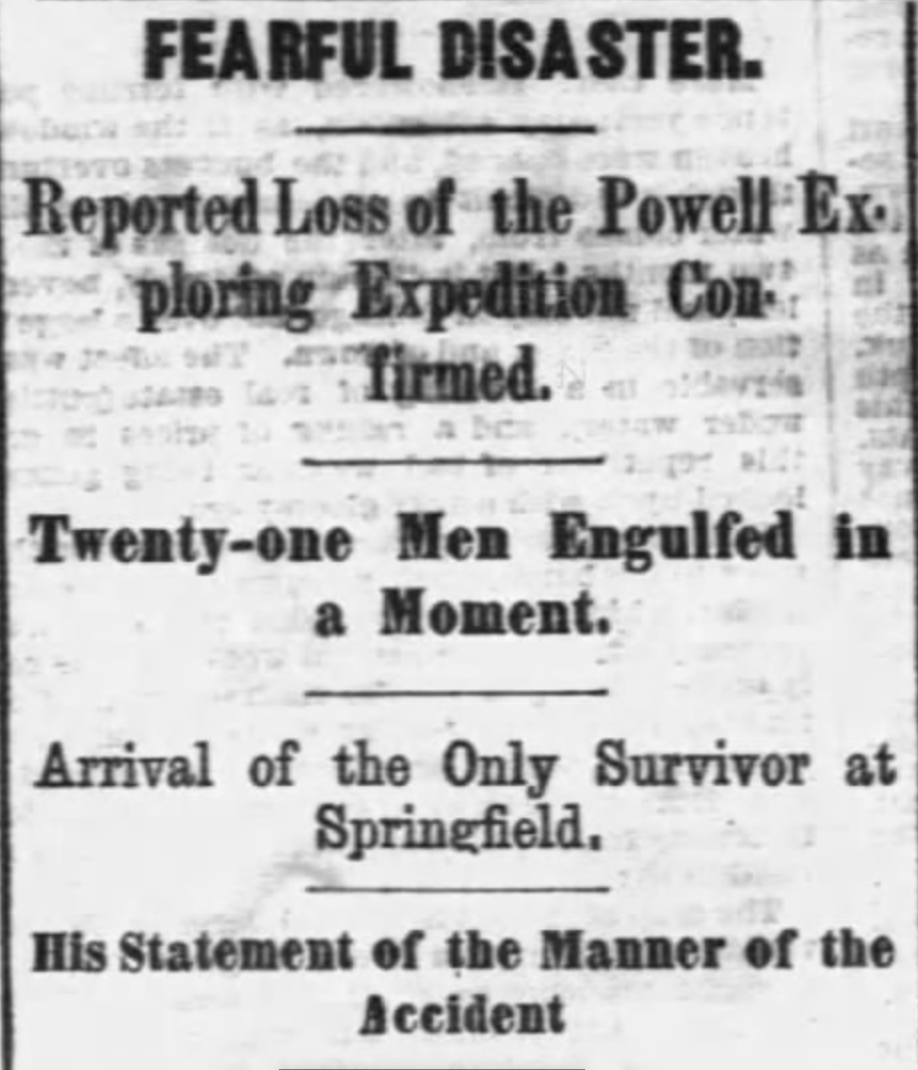

July 3, “Fearful Disaster. Reported Loss of the Powell Expedition Confirmed.”

John Risdon, if that was even his real name, told a particularly colorful tale to the Chicago Tribune about his supposed experience with the revered expedition.

He recalled all but two of the 21 crew members’ names — middle initials included— who drowned in the rapids of the Colorado River on May 16th or 18th. Risdon survived because, for some reason, he had stayed behind to make lunch.

The reporter, who apparently missed word of the actual expedition leaving on May 24th, said Risdon had “the appearance of an honest, reliable man” and rapidly jotted down his account;

“Risdon stood on the shore waving his hat, and said: ‘You must be back in time for dinner, for I will have a good lunch for you when you return.’

They cried back in reply, ‘Good-bye Jack; you will never see us again.’

A moment later, Risdon saw the boat commence whirling around, and like a living thing dive down with its living freight, Major Powell standing at his post, and that was the last Risdon saw of this noble and ill-fated expedition…”

The story was published on July 3rd while Powell and a few others were at a reservation near the Uinta River sending letters, trading supplies, and learning about the Utes. Of course, once Powell’s letters got back to his wife in Illinois— who already knew Risdon’s story was bologna, the newspaper published them as a remedy.

July 4, Goodman out

Frank Goodman, who had joined the group who went to the reservation, decided to throw in the towel. It turned out that nearly drowning, getting caught on fire, carrying oak boats over rocks, and eating rancid bacon wasn’t how he wanted to spend his summer anymore.

Powell wrote, “As our boats are rather heavily loaded, I am content that he should leave, although he has been a faithful man.”

Meanwhile back at base camp on the Green River, George Bradley was in a reflective mood that Independence evening. He had joined the expedition to get out of the military, which proved to be more of a tribulation than he’d expected.

“But those green flowery graves on a hillside far away seem to answer for me, and with moistened eyes I seek again my tent were engaged with my own thoughts, I pass hours with my friends at home, sometimes laughing, sometimes weeping until sleep comes and dreams bring me into the apparent presence of those I love.”

July 6, “Potato tops are not good greens on the sixth day of July.” – Jack Sumner

The crew is reunited and promptly flowing again with the Green River. Shortly into the drift, they came to an island near the White River where Powell suspected a garden.

John Wesley had camped in the White River Valley the winter prior and met an interpreter who was planning to do some planting on the Green. When he learned of Powell’s upcoming journey, he told the Major to help himself to what sprouts.

Sure enough, the fleet found it. Not much had succeeded except for some potato tops, which 18-year-old Andy Hall said were fine eats. They were for a stew, which immediately poisoned everyone but George Bradley and Seneca Howland who had decided to pass on account of the taste.

Powell wrote, “Emetics are administered to those who are willing to take them, and about the middle of the afternoon we are all rid of the pain.”

Despite their temporary tummy aches, the men still managed to make 37 miles and kill four geese along the way according to Jack Sumner’s journal entry that day.

July 7, Enter the Canyon of Desolation

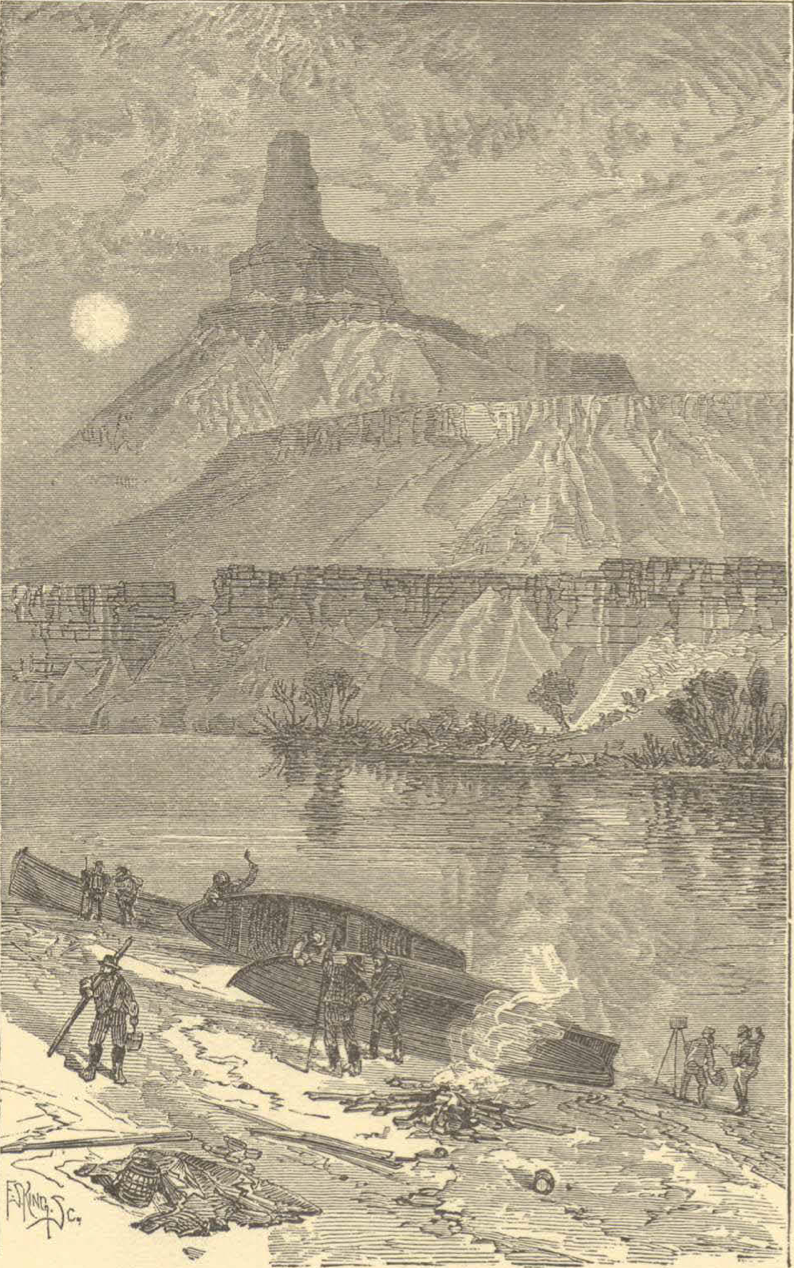

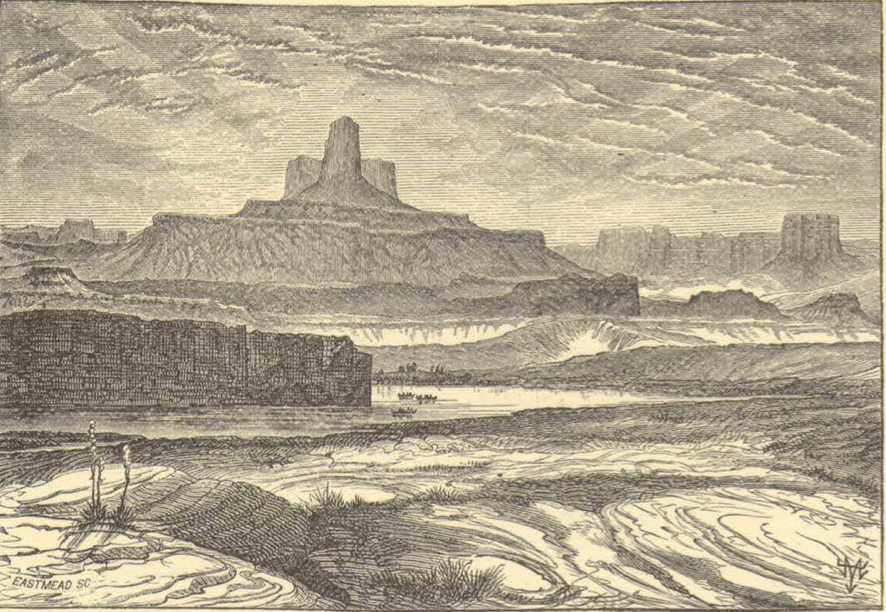

As the walls began to close again on the Green River, the men stopped to survey the cliffs first thing that morning. Many took an appreciative note of the new, colossal scenery rising before them.

“In these quiet curves vast amphitheaters are formed, now in vertical rocks, now in steps,” Powell wrote.

“There are also side canons coming in every quarter of a mile making the top of the Plateau look like a vast field of honeycomb,” from a usually blunt Jack Sumner.

George Bradley had his own special experience as they climbed the plateau. Not noticing it at first, he scrambled over an ancient dwelling hidden among the eroding sandstone. He stopped and fixed the inflicted bricks, then secured the structure with a larger rock, and left his sign of the expedition.

“It is the first time I left my name in this country for we have been in a part that white men may have been before, but we are now below their line of travel, and we shall not probably see any more evidence of them until we get to White River no. 2 below here.”

Back in the boats, they ran the next lot of rapids successfully, covering 40 miles according to Bradley, or 34 according to Sumner, or 26 according to Powell.

July 8, Desolation Blows

During the day, Powell had made mention of the annoying, multi-current head gales holding up the crew’s progress. But those daytime breezes were only an introduction to Desolation’s “gusto.”

In a long, fun-shaped chasm like Desolation Canyon, cold air mixing with hot becomes, as Bradley put it, “…music fit for the infernal regions. We needed only a few flashes of lightning to meet Milton’s most vivid conceptions of Hell.”

With winds whipping up to 70 mph, the beaches where the men camped were resurrected to bounce between the walls that made them.

July 10, Bustified like a Forty Pounder

Today would be the highest climb yet as Powell and Oramel Howland ascended 4,000 feet to the canyon rim. At the top, Howland scampered off in hopes to snag a deer while Powell summited a nearby peak where “a fine view [was] obtained.”

Meanwhile in camp, Bradley was rewriting his soaked journal entries and listening to Andy Hall belt out “… a song that will no doubt someday rank with America and other national anthems,” he said.

“When he put his arm around her she bustified like a forty pounder, look away, look away, look away in Dixie’s land.”

The surveyors, still 4,000 feet up, met again at sunset. Since Howland was unsuccessful and night was falling, they began bounding down the walls and “leaping over ledges” until they were unable to see.

Luckily, the camp had kept the fire blazing to which they followed as Powell recalled: “in a long, slow, anxious descent.”

July 11, Em sends ‘Em Swimming

The pilot boat, Emma Dean, was promptly oarless after the first rapid of the day. And without an obliging forest nearby, the boys decide they needed to float a little farther to find timber.

Soon after the river would cut sharply to the left with a pompous swing of rapids. In their attempt to avoid becoming one with the canyon wall, Powell, Sumner, and Bill Dunn were rinsed and flipped from their steerless skiff. Despite his one-armed stroke, Powell wrote in his journal that he had no trouble swimming.

Jack Sumner clarified in 1907 (five years after Powell had passed) that the Major did in fact wear an inflatable flotation device through bad rapids. It was the only life preserver on the trip and most likely saved Powell from drowning in multiple circumstances such as this.

After the three landed the boat and came to shore with the others, they counted their new losses which included a barometer, two rifles, and most of the blankets.

Powell salvaged one blanket as it floated by, but deduced with yet another dwindling necessity, “…sometimes hereafter we may sleep cold.” And they would.

July 12, Bradley’s Quick Dip

Breakfast delivered mostly easy whitewater, until, of course, an “old roarer” as Bradley described emerged beside an overhanging cliff.

Having already portaged 10 rapids, the crew decided to run it. The plan was to keep to the left to avoid certain death, or at least a very good boat bonk, on the right.

All succeeded, except for the Kitty Clyde’s Sister which slipped into a chute which then delivered it to the danger zone on a silver platter.

Powell recounted as the crew watched the boat become manhandled in the waves, “Bradley is knocked over the side, but his foot catching under the seat, he is dragged along in the water, with his head down; making great exertion, he seizes the gunwale with his left hand, and can lift his head above water now and then.”

While water-boarded Bradley was preoccupied, William Powell took to the oars and pulled like a mad man away from the cliff. He prevailed, and then quickly pulled Bradley back into the boat, making him the understated badass of the day.

After a quick portage, it was business as usual and the crew floated into Coal Canyon (later renamed Gray Canyon) that they creatively named after finding some coal beds.

That night, Powell noted, “The wind blows a hurricane” and the boys once again slept buried in sandbanks.

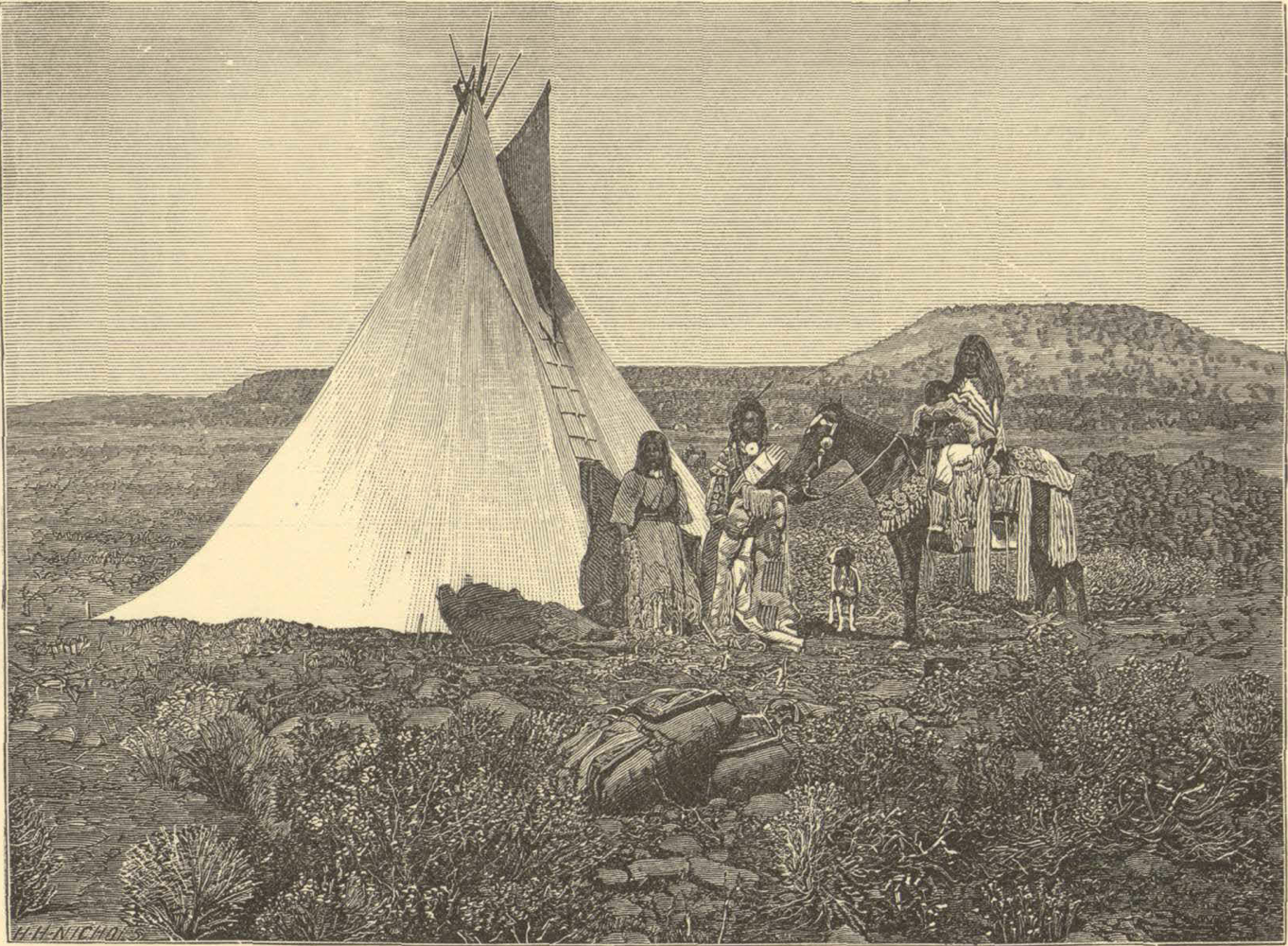

July 13, Company at White River no. 2

“About two hours from noon camp, we discover an Indian crossing, where a number of rafts, rudely constructed of logs and bound together by withes, are floating against the bank. On landing, we see evidence that a party of Indians has crossed within a very few days. This is the place where the lamented Gunnison crossed, in the year 1853, when making an exploration for a railroad route to the Pacific coast.”

John W. Gunnison had previous success in resolving disputes with Native Americans. But when he and his group of explorers reached the Sevier River, they were immediately murdered their first night in camp.

The killings were attributed presumably to the Paiute tribe; an indigenous group that resisted Mormon settlements throughout Utah in the 19th century.

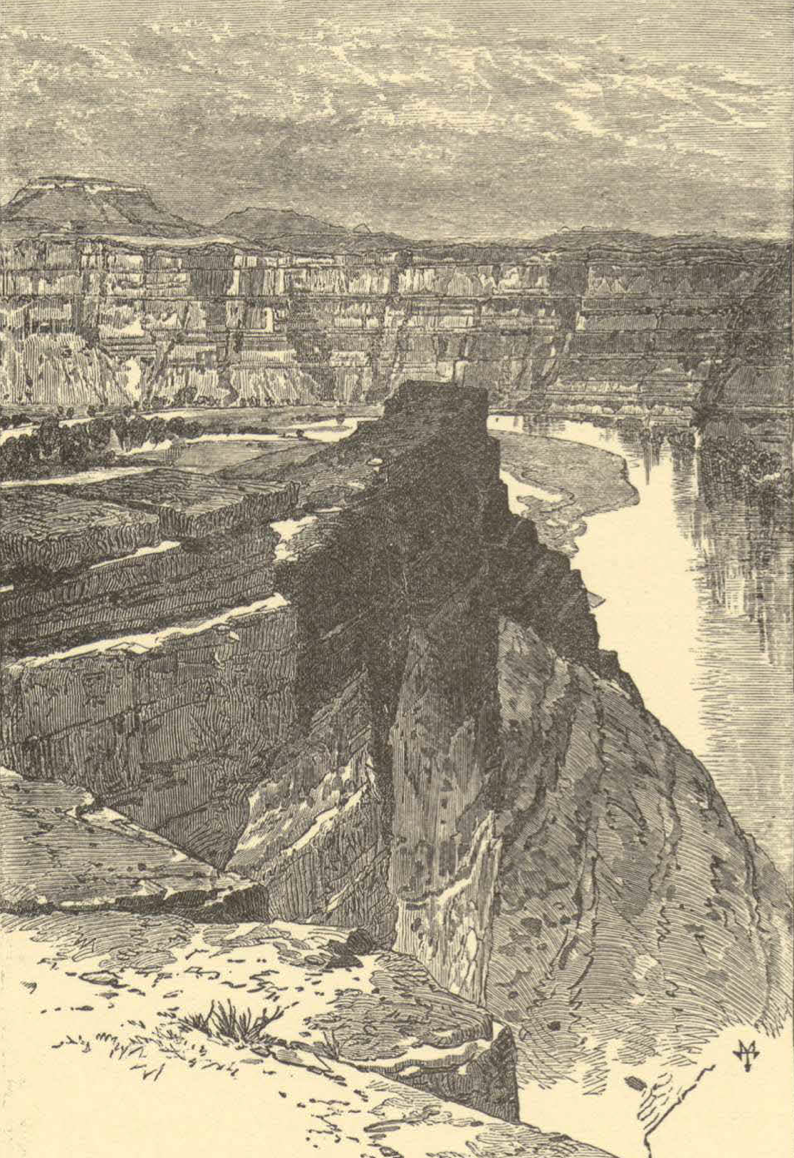

July 14, Enter Labyrinth Canyon

They greet a perpendicular canyon starkly unfamiliar to the stair-step escarpments where they’d just spent their week. In the winding stillness of Labyrinth Canyon, thoughts simmered in the crew like the sun against the orange sandstone.

Bradley wrote, “Hardly a bird, save the ill-omened raven, or the occasional eagle screaming over us; one feels a sense of loneliness as he looks on the little party, only three boats and nine men, hundreds of miles from civilization, bound on an errand the issue of which everybody declares must be disastrous.”

But Powell and the rest of the men seemed to be enjoying the labyrinth, quietly admiring the caves and alcoves, its symmetrical walls, and the disorienting reflections belying the glassy waters.

Still enjoying the peacefulness on July 15, Powell wrote, “…the badinage of the men is echoed from wall to wall. Now and then we whistle, or shout, or discharge a pistol, to listen to the reverberations among the cliffs.”

July 17, Toom’-pin wu-near’ Tu-iveap’

As the men exit Stillwater Canyon, it would mark the utmost anticipated, momentous meeting with the Colorado River, and thus, the oncoming calamity of Cataract Canyon.

To continue reading about Powell’s expedition through Cataract Canyon click here.

More Reading

The Geology and History of Desolation Canyon

Real River Runners Write Letters – Herm Hoops and River Conservation